ᓱᕕᓇᐃ ᐊᓲᓈ

Mapping Worlds

ᓄᓇᙳᐊᓕᐅᕐᓂᖅ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᙳᐊᓂᒃ

Produced with the support of the Frederick and Mary Kay Lowy Art Education Fund

As a title, Mapping Worlds can be heard as a description of Ashoona’s ever regenerating and expanding drawing practice. Mapping can also be found in the act of visiting the exhibition, where your navigation between works and in the thick of their details might inform a sort of cartography bringing you to think differently about Inuit art, life in the North, internal and external worlds, and a sense of ecology at once grounded in actuality and fed by the imagination.

Read moreIn this instance, ways of thinking about Ashoona’s work is as much a form of wayfinding as an exercise in critical analysis. What ways can you find through Ashoona’s worlds? From where do you start? Where do you find footing across her spatial and imaginative terrains? How do you familiarize yourself with the people, animals, entities, and communities that populate them? Can disorientation be part of this process?

Below are some suggested points of focus to open up pathways among the works in the exhibition. These prompts can be combined with the contextual notes and extended labels authored by the curator and providing details on art production in Kinngait, Nunavut, background on Ashoona’s career, and close readings of three key works.

CloseArtist

Shuvinai Ashoona was born in 1961, in Kinngait, Nunavut, Canada, where she lives and works. Solo exhibitions of Ashoona’s work have been organized at Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum, Iqaluit (2013); MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina (2012); Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa (2009); and Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton (2006). Her work has been shown in group exhibitions at venues including the Esker Foundation, Calgary (2017); Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2017); Mercer Union, Toronto (2016), National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2014) and SITE Santa Fe (2014). Most recently, Shuvinai Ashoona received the 2018 Gershon Iskowitz Prize.

CloseCurator

Dr. Nancy Campbell has been a contemporary art curator for the past twenty years. She has held positions at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the University of Guelph, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection and The Power Plant. In 2006 she curated an exhibition for The Power Plant of the work of Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook that travelled nationally and internationally, propelling Pootoogook to be included in Documenta 12 and winning the Sobey Art Prize in 2007. Her work with Shuvinai Ashoona began with a two-person exhibition at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto titled Noise Ghost: Shuvinai Ashoona and Shary Boyle. Since that time Campbell has focused her curatorial practice on the contemporary Inuit producing many exhibitions attempting to bridge the Inuit with the contemporary art.

CloseKeywords

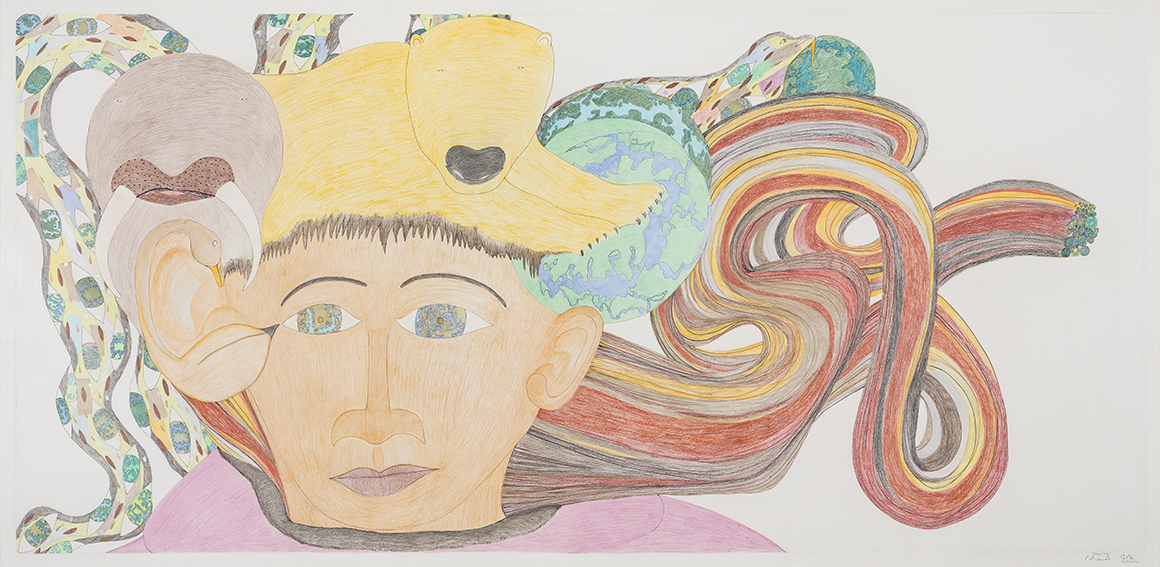

“Mapping” is perhaps nowhere more pronounced than in the multitude of globes surging through Ashoona’s drawings. As a recurrent motif each globe is an invitation to look again.

Spotted with an endless variety of continents, Ashoona’s globes parade down the street in To the Print Shop, 2013. Globes rest on the seabed among schools of fish as fishing hooks and line descend from above in Composition (Fish, Baleen, Globes, Pebbles), 2018 and they swim between clams in Untitled (Clams and Globes), 2010. A massive salmon-skinned creature crams globes into its sharp-toothed mouth while others bubble up under its skin in Untitled, 2017. A pregnant woman’s belly swells with a new planet, as two larger globes are orbited by fish, tools, dwellings, and decorated eggs and fruit in Untitled (Woman Giving Birth to the World), 2010. Eyes watch throughout, their irises replaced by globes.

More than celestial objects, Ashoona’s globes are active participants in her worlds. Near ubiquitous, they’re found under rocks, under skin, in dialogue with humans and animals. They form bodies and emerge from them. They inhabit worlds as much as they are inhabitable worlds.

They are also deceptively simple drawing activities: a circle, lines for coasts, blue for water, green and brown for land. Provisional and spontaneous, each composition adds a new variation. Their breadth represents the vitality and possibility they promise to hold as worlds, as well as what can be found in the contemplative act of drawing.

EXPLORE

- Look closely at the different scales and types of the terrestrial: globes, built structures, rocky landscapes, seabeds, crevasses, and underworlds.

- Consider the ways the globes interact with people, animals, and creatures.

Photographers can be seen traveling through works in the exhibition. As a minor figure amidst Ashoona’s ever-growing cast, they offer a shoulder to look over for another angle of view.

Pinned under the clawed foot of a hirsute giant in Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2015, a photographer reaches to snap a photo of a small blue tentacle creature scurrying by beneath the bedlam. Sat among a scattered array of bones in Posting Bones, 2015, two people train their phones on a reassembled animal skeleton. Camera in hand, a figure in a helmet and heavy suit peers out from behind a stone as a crowd of creatures crawl across the rocky terrain in Creatures, 2015.

Photography here introduces a sense of time, history, and transmission to Ashoona’s work. There is a before and after to the attack, a record of the creatures’ congregation, the sharing of photos of the carefully balanced bones. Carried around densely cohabitated worlds, the camera as an objective tool plays witness to these episodes and apparitions. At the same time, the activity within Ashoona’s worlds carries on irrespective of the camera’s gaze, its scale and range of life too vast, too vibrant, too lively to be captured and contained within any single frame.

EXPLORE

- Shift your view to that of the camera’s lens. How does this reorient your understanding of the scene? What forms of looking does a camera or phone elicit?

- Look for photographs as objects in Ashoona’s compositions. What do they depict? How do they work in relation to the overall frame of the work? What sort of sense of time do they introduce?

Many of Ashoona’s compositions are held together through acts of touching, contact that speaks to the density of her worlds and the associative connections she makes in her drawing process.

At its most dramatic this can be seen in Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2015 in the clash between two giants, a tangle of orange and grey tentacles, while a hand from out of frame grabs a stray, flailing limb (and likewise in Composition (Creature Invasions), 2017). In Creatures, 2015 slender, coloured snake-like figures wrap around each other, a yellow creature rests its paw on a cowering blue neighbour, a hybrid fish-like figure nurses two offspring, and, in the centre, a young creature peeks out from its guardian’s amauti hood. In Composition (Red Headed Octopus), 2016 one set of tentacles touch and fuse to the rocky landscape, while another fans out, connecting and framing a set of images of people and worlds. Finally, Family Portrait, 2014 shows intimate chains of connection through arms draped over shoulders and wrapped around waists.

Tentacles, fingers, limbs, and bodies all feel their way through Ashoona’s drawing. These are tentative and lateral moves—they crawl across terrain, they reach between worlds and beings, they pull people and creatures in and hold them close, as if no one is to be left out. Connecting and overlapping, they form a netting, a dense braid outlining the mutual entanglements and interconnection that give form to her worlds.

EXPLORE

- Where does contact end and metamorphoses start? Look for the blurred lines where people, animals, creatures, and the landscape begin to fuse together.

- The ways these connections reach out of frame. Take note of instances where figures look back at you, the viewer.

Cryptic and disjunctive text in both Inuktitut and English plays an important, if at times subtle, role in Ashoona’s compositions. Reading Ashoona’s work helps feel out the place of the intangible and still in formation in her works.

In Untitled, 2017 eleven people work away individually at large sheets of paper. An overhead angle offers a global view on their writings: lists of Biblical cities mixed with major Canadian cities; notes on the horror film The Exorcist (a favourite of Ashoona’s) and its star, Linda Blair; superheroes’ names; dates and budgets; and personal notes. In Composition (Clams and Globes), 2010, tightly written text ring the clams’ long, ribbed protruding siphons. Amid these exhaustive lists in Inuktitut syllabics on the use and characteristics of clams is a line in English: INVISABLE [sic] CLAMS FOREVER AND FOREVER. The texts read on clothing in Family Portrait, 2014 span graphic, declarative, and introspective modes, sharing information, half-finished acts of naming, and internal refrains.

This use of both Inuktitut and English text brings up questions of legibility and fragmentation: Whom is this addressed to? Who can read this? Yet, this play with access may be less about boundaries in communication than it is about the interaction between the visible and invisible. Carried by the body on clothing or inscribed directly on flesh or written down on a page, the texts relay emotional and psychological states, preoccupations, and fascinations. They also address the viewer. Small, tightly inscribed text guide looking towards reading, tempting fleeting narratives and connection with elements left undrawn.

EXPLORE

- How Ashoona works with surfaces—terrain, skin, clothing, shells—as occasion for communication. Where does the text appear or behave as a part of nature? Where does it offer commentary, witness, or testimony? Does it always play the role one would expect on clothing or paper?

- In what ways would you describe what you see? How would you narrate Ashoona’s drawings?

Close

Key Works

Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands), 2007

Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands), 2007

Fineliner and coloured pencil on paper

Courtesy Edward J. Guarino

Qaujimajatuqangit is a body of knowledge that rests on a belief in the interconnectedness of life. This way of thinking is aptly reflected in this work, an expressive, boisterous circular composition drawn from Shuvinai Ashoona’s mind. In this drawing, a group of figures, hand in hand, form a ring around a brown bear, overlaid by a polar bear, overlaid by a seal, and finally by a char on top.

The human figures in the composition are primarily Inuit, presented in both traditional and contemporary dress. On the right, a half-white, half-Inuit mother nursing her children is embraced from behind by an elder who sits directly across from a kneeling figure with two children in the hood of her green amauti parka. Interspersed alongside them is a winged narwhal with one flipper and one hand and a Sedna (sea goddess) wearing one kamik (boot); the planet Earth—with arms and hands—completes the circle.

Ashoona remarks on the composition: “I was thinking that they were having a meeting, a world meeting about the seals, polar bears . . . rethinking what the world would be for the animals. I started thinking that all of these animals would be friends, even some of the dangerous animals I have seen in the movies are there.”

Close Earth Transformations, 2012

Earth Transformations, 2012

Coloured pencil and Conté crayon on black paper

Courtesy Martha Burns and Paul Gross

Earth Transformations, 2012, is one of many works completed by Shuvinai Ashoona between 2011 and 2014 that feature a globe. The planet appears in many combinations, including piles of globes, links of globes connected by harpoons or lightning bolts, and faces and body parts made of globes. Though rendering geographically “accurate” depictions of the continents does not preoccupy Ashoona, she consistently represents globes as “‘earthlike’ and/or suitable for life.”

The large globe in the upper left is an aerial view of a community complete with wildlife: a walrus, a caribou and a lemming are running about. The globe seems to grow out of two human legs, complete with sky-blue toenail polish on the feet. Circling the legs are the tentacles of an octopus—dark purple with blue undersides that have suction cups—stretching through the lower half of the picture plane. The arms of the figure are made of strings of globes with clawed hands that seem to be grasping for something. On the far right, an Inuk dressed in a traditional parka and kamiks (boots) is holding up a drawing (a motif Ashoona has used before). One of his arms is also made of globes with a clawed hand. The inset drawing shows a hunter holding a rifle and kneeling behind a stretched canvas, perhaps using it as a blind to camouflage himself. Thus, Ashoona has created two levels of inset images: the man holding a canvas depicting a hunter holding a canvas, presumably of the same Kinngait landscape pictured in the first inset.

Close Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2013

Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2013

Fineliner and coloured pencil on paper

Courtesy Paul and Mary Dailey Desmarais III

Attack of the Tentacle Monsters, 2013, is a major evolution in Shuvinai Ashoona’s practice. Surreal elements reveal her increased sense of freedom in juxtaposing fantastical monsters, sea creatures, people and popular culture, all depicted in rich colour.

A bright orange octopus, to the left, has the hairy legs of a wolf-like beast with large red claws. Oddly-shaped eyes circle the octopus’s head, peering in all directions. This octopus joins tentacles with a grey octopus, to the right, with the white legs of a human. Instead of eyes, human faces circle its head, each with different skin tones and hair colours typical of Ashoona’s representation of humankind. In the centre a white, blond-haired man in a bright green parka stands with his arms raised and his mouth open in alarm. The background is a detailed rocky terrain typical of the Arctic. A photographer, crouched beneath the large paw of the monster on the right, oblivious to the drama unfolding above him, focuses his lens on the small dancing creatures before him. At the left edge of the picture plane, we see a human arm attempting to pull the orange monster away. There are seldom explanations for Ashoona’s imaginings; rather, they appear as dramatic stories that delight the artist herself.

CloseContext

“Our carvings were increasing and there was a collection of prints gathered down south, so with Joanasi Solomoni as interpreter, we learnt more and more about co-ops. I began to think that a co-op would be better than the traders, and as I heard more and more about it I decided that if we could have a co-op we could have two stores here and that would be better, for the prices of things would be lower. A co-op however would help the people even more than the B.T.C [Baffin Trading Company] for now the people were no longer poor and could help themselves through the co-op with carvings and prints.”

-Board member and artist Kanaginanak Pootoogook, 1959

Over the years the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative developed a network of dealers across North America, and established Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto as an intermediary between the Cooperative and the dealers. The Cooperative organized community visits for artists from the South travelling in the North, and fine arts programs for the benefit of Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset) artists, including printmakers and carvers. To date, it is the longest running printmaking studio in Canada. Shuvinai Ashoona is a member of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative and lives in Kinngait.

CloseInuit art has been slow to hit the radar of international curators. Gradually through the work of artists like Shuvinai Ashoona, whose drawings and prints challenge outdated expectations of what Inuit art should look like, Inuit artists are gaining international attention beyond the traditional Inuit market system. Ashoona’s work was included in an exhibition of Canadian art, Oh Canada at MASS MoCA (North Adams, Massachusetts), curated by Denise Markonish in 2013; and in Unsettled Landscapes at SITElines, SITE Santa Fe (New Mexico), curated by Candice Hopkins and on view from July 2014 to January 2015. These recent inclusions of Inuit art speak to the increased accessibility of material online, and to the gradual inclusion of Inuit art in contemporary art exhibitions.

Ashoona is featured in the 2015 Phaidon publication Vitamin D2 New Perspectives in Drawing which introduces a new generation of artists engaging with drawing in innovative ways. Inuit art is constantly changing and adapting, like Inuit culture more broadly, and Ashoona is pivotal to this change. Shuvinai Ashoona: Mapping Worlds is her first major solo museum exhibition.

CloseComplementary resources

Balzer, David. “An Interview with Shuvinai Ashoona” The Believer (November/December 2011). https://believermag.com/an-interview-with-shuvinai-ashoona/

Blodgett, Jean, ed. Three Women, Three Generations: Drawings by Pitseolak Ashoona, Napatchie Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona. Kleinburg, ON: McMichael Canadian Art Collection, 1999.

Boyd Ryan, Leslie, ed. Cape Dorset Prints: A Retrospective; Fifty Years of Printmaking at the Kinngait Studios. San Francisco: Pomegranate Communications, 2007.

Campbell, Nancy. Noise Ghost and Other Stories. Toronto: Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, 2016.

— — — — —. Shuvinai Ashoona: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2019. Also on-line at: https://aci-iac.ca/art-books/shuvinai-ashoona

Dyck, Sandra. Shuvinai Ashoona: Drawings. Ottawa: Carleton University Art Gallery, 2012.

Haraway, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene.” e-flux journal no. 75 (2017). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/75/67125/tentacular-thinking-anthropocene-capitalocene-chthulucene/

Hunter, Andrew. The Polar World: Shuvinai Ashoona. Toronto: Art Gallery of Toronto, 2017.

Karetak, Joe, Frank Tester and Shirley Tagalik, eds. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit What Inuit Have Always Known to Be True. Halifax: Fernwood, 2017.

Mitchell, Marybelle. From Talking Chiefs to a Native Corporate Elite: The Birth of Class and Nationalism Among Canadian Inuit. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996.

Saladin d’Anglure, Bernard. Inuit Stories of Being and Rebirth: Gender Shamanism, and the Third Sex. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2018.

Sanadler, Daniella. “Soft Shapes & Hard Mattresses: Sex and Desire in Contemporary Inuit Graphic Art and Film.” Inuit Art Quarterly 32 no. 2 (Summer 2018): 40-47. http://iaq.inuitartfoundation.org/erotic-inuit-art/

Sinclair, James. “Breaking New Ground: The Graphic Work of Shuvinai Ashoona, Janet Kigusiuq, Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, and Annie Pootoogook.” Inuit Art Quarterly 19 nos. 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2004): 58–61.

Stern, Pamela, and Lisa Stevenson, eds. Critical Inuit Studies: An Anthology of Contemporary Arctic Ethnography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Close