SIGHTINGS 2025-2027

Decorum

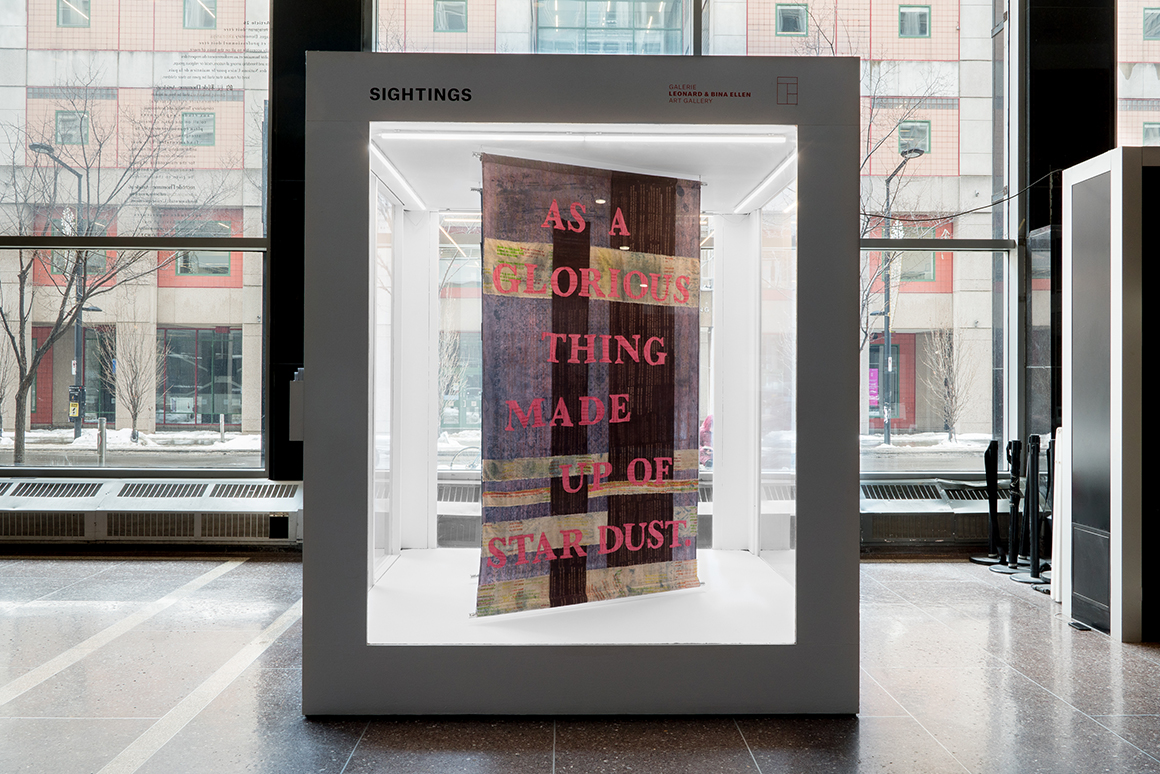

Launched in 2012 in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery’s Permanent Collection, the SIGHTINGS satellite exhibition program was conceived as an experimental platform to critically reflect upon the possibilities and limitations of the modernist “white cube.” As part of this program, artists and curators are invited to develop projects for a cubic display unit located in a public space at the university, with the aim of generating new strategies for art dissemination.

The 2025-2027 SIGHTINGS cycle, Decorum, engages with the emancipatory histories of Concordia University’s Henry F. Hall Building. Since its inauguration in 1966, the building has been a key site for student activism—from the 1967 lobby sleep-in protest against high textbook prices, where 150 students camped in the lobby, to the landmark 1969 Sir George Williams Affair, marked by a multi-day occupation of the 9th-floor Computer Centre by students and demonstrators to denounce racist grading practices. Originally conceived as a central hub for the downtown student body, the Hall Building remains a space where students gravitate to exchange ideas, mobilize and make their voices heard. The projects presented in SIGHTINGS build on this legacy, reflecting on the memory of protest embedded in institutions and their architecture.

SIGHTINGS is located on the ground floor of the Hall Building: 1455, blvd. De Maisonneuve West and is accessible weekdays and weekends from 7 am to 11 pm. The program is developed by Julia Eilers Smith.

Never Was a Man

Swapnaa Tamhane’s art practice is dedicated to the material histories of cotton and jute, which led to making handmade paper, archival research, and textile installations. She collaborates closely with artisans in Kutch, Gujarat, India, in a skill-sharing process. Tamhane holds an MFA in Fibres & Material Practices from Concordia University, Montreal. Past exhibitions have been held at Nature Morte, Delhi; articule, Montreal; Sculpture Park, Jaipur; Green Art Gallery, Dubai; Victoria & Albert Museum, Dundee, Scotland; with solo exhibitions at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and Surrey Art Gallery, Surrey. Upcoming exhibitions will be held at the Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts, and The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

The artist wishes to thank Salemamad Khatri, Abdulaziz Khatri, Aman Sandhu, Julia Eilers Smith, and Pip Day.

Natural and synthetic dyes on industrially produced cotton, mirrors on steel dowels

Block printing and dyeing by Salemamad Khatri

Block carving by Pragnesh Prajapati

87 ½ × 52 inches each

With assistance from Madison Strižić and Hannah Ferguson

Content warning: The following text discusses suicide.

I remember reading these words.

They have stayed with me.

Words from a letter.

They were written by Rohith Vemula.

This letter was his last.

A PhD student. At the University of Hyderabad.

He took his life on January 17, 2016.

He wrote:

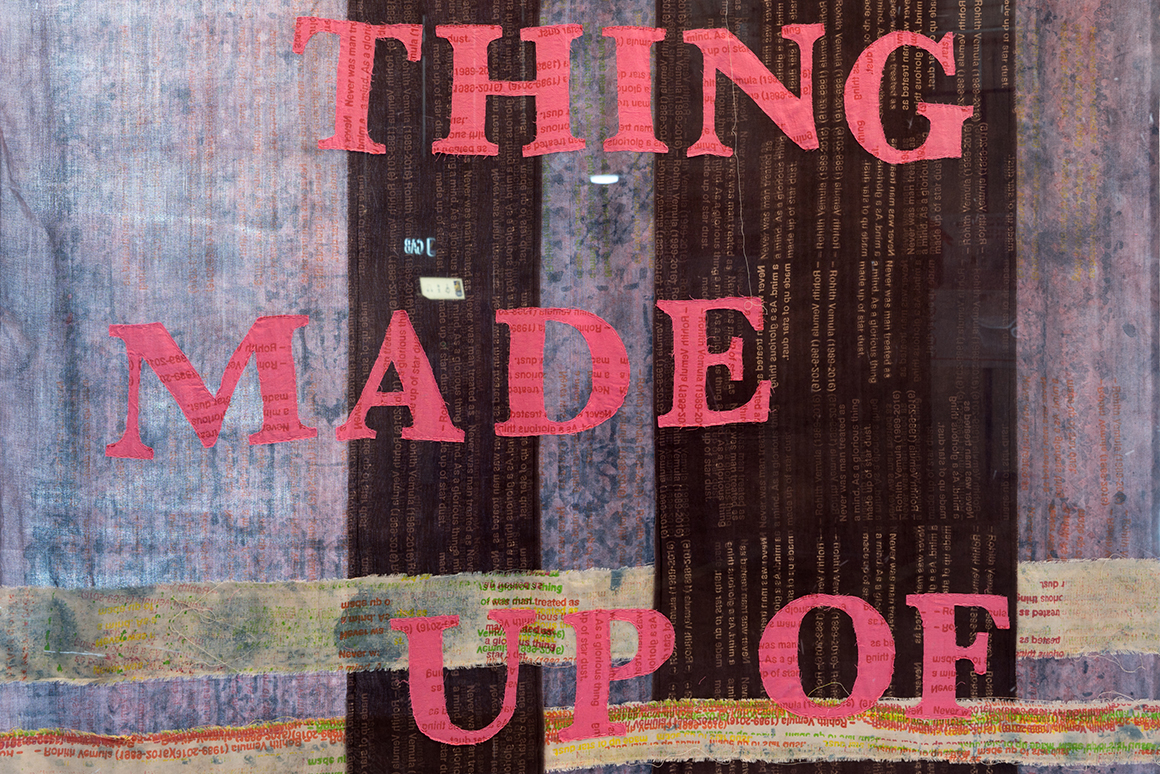

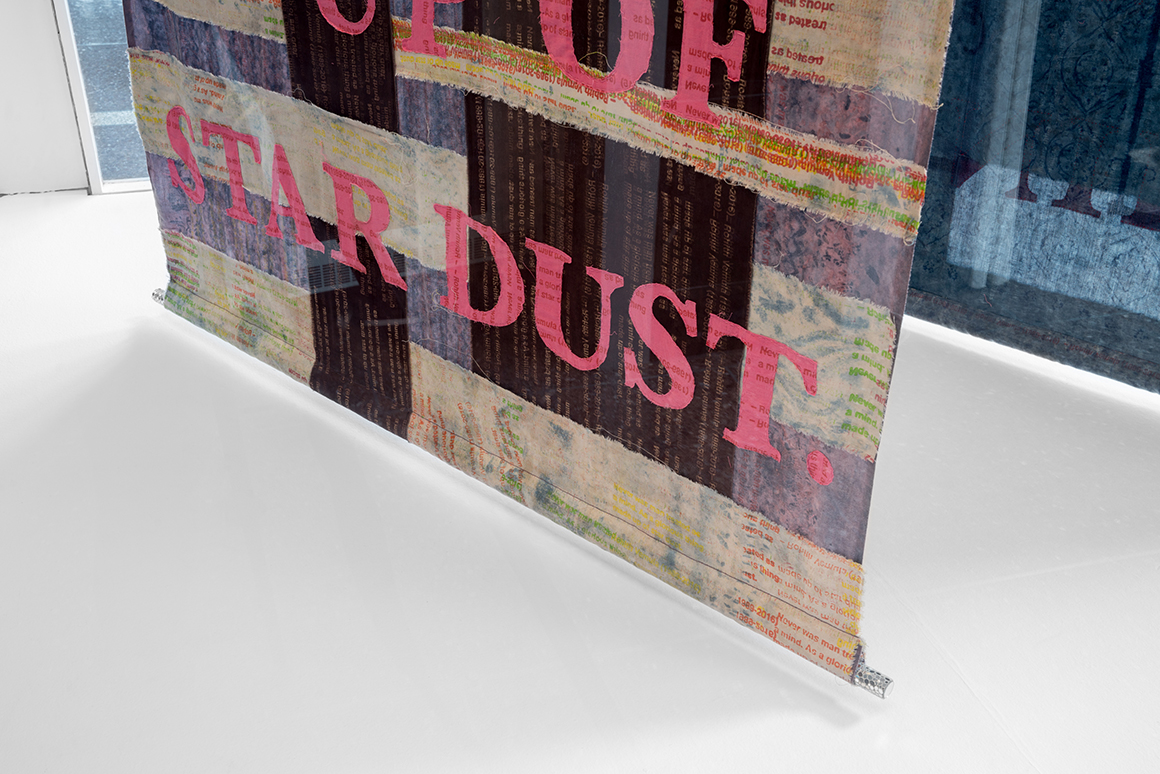

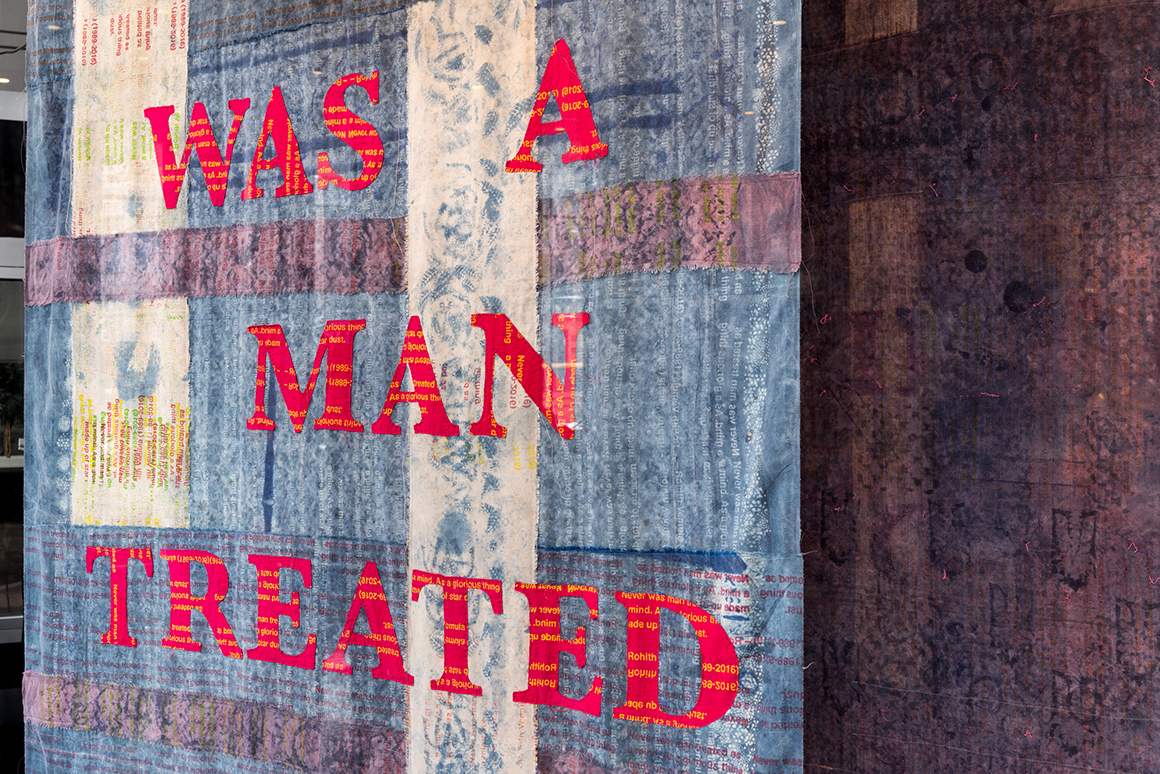

“The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of star dust. In every field, in studies, in streets, in politics, and in dying and living.”

Somehow, Rohith understood his humanity, his preciousness, his value, far better than any system or society could.

In his letter, he proclaimed: “My birth is my fatal accident.”

Rohith was studying sociology. He was first studying biotechnology but switched to the social sciences because of his passion for the issues that shape society.

Which he understood more than others.

Rohith was Dalit.

His words have stayed with me.

Indeed, they have stayed with all of us.

His words galvanized student protests across India. They brought to the surface the seeped-in discrimination of the caste system that finds its way onto these reputable university campuses and impacts students from marginalized communities.

This discrimination is built into the very architecture of Hinduism.

Public universities in India have a reservation system designed to enable access to higher education for Dalits, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Castes, and other minorities—also known as Bahujan (the many). Often, these students come from rural, agrarian backgrounds, and speak little English. Once on campus, they are placed alongside privileged caste students and taught by privileged caste professors, with all instructions and readings conducted solely in English.

They face caste discrimination in obvious and subtle ways: sometimes, their fellowship payments are delayed, or if they wish to address the lived experience of being from lower castes, some professors simply refuse to engage. Not to mention the canteen.

The reservation stain.

As it’s known.

Rohith was a first-generation PhD student.

He was a voracious reader of Dalit literature.

He wanted to be a writer like Carl Sagan, he wrote in his letter.

Political leader Dr. Bhimrao R. Ambedkar’s document on States and Minorities for the

Constitution of India (which came into effect January 26, 1950) included articles for the protection and empowerment of the Scheduled Castes (or what he called “Untouchables,” now Dalits), including the abolition of untouchability, legal punishment for any discriminationatory act, and the introduction of reservations. While the reservation system holds 15% of university seats for Dalit students, their education does not necessarily always lead to academic positions or elite jobs.

Prior to Rohith’s suicide, nine other Dalit students from that university had also taken their lives.

Rohith hung himself with a banner from the Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA), to which he belonged. The Association was founded in 1993 by Dalit students to provide representation on campuses and fight against right-wing Hindu fundamentalist groups.

The banner was blue.

Blue like Dr. Ambedkar’s suit.

Blue like the flag of the Dalit movement.

Blue like indigo.

Rohith, along with four other PhD students from the ASA, had been suspended by the Vice Chancellor when a student claimed he had been assaulted by them.

Actually, he had appendicitis.

The student in question was part of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), a student-wing of the pro-Hindutva Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) party. The ASA, it is worth noting, in contrast, is unique in that it is not linked to any political party.

Political parties have their representation on campuses across the country, from the

Congress party to the BJP (which, since 2014, has held the majority, until losing seats in the 2024 election). Vice Chancellors are instated by political parties, and the Central

Government insisted the university take action against Rohith and his fellow students after the alleged assault.

Their fellowships were halted, they were banned from public spaces, as well as private ones like their hostels, and administrative buildings.

After being forced to sleep outdoors in what he called Velivada (Dalit Ghetto),

Rohith wrote a letter to Vice Chancellor Appa Rao Podile on December 18, 2015. In his letter, he suggested that Dalit students should receive poison along with their admission to the university. He also suggested that ropes be supplied to all the rooms of Dalit students.

His anger was palpable.

Less than a month later, he hung himself.

Not with a rope, but with an ASA banner.

In his friend’s hostel room.

Room 207.

There were several images of Ambedkar and Buddha hung high up around the room, above the window, on the yellow walls.

At eye-level from the ceiling fan where he attached the banner.

Maybe they gave him some solace.

_______

His letter was circulated widely.

It went viral.

Student protests began at 7:30 am on January 18.

Hunger strikes.

“Kadilindi Dalita Dandu…Khabardar, Khabardar” (The Dalit movement has begun… Beware, Beware.)

Demands that the Vice Chancellor step down.

Rohith’s mother led the protests.

His suicide was discussed in both houses of Parliament for several days.

It was a historic moment.

The university attempted to absolve itself of responsibility for Rohith’s death by claiming that he was not Dalit.

It continues to do so, even nine years after his death.

_______

His words have stayed with me.

I wanted his words to be endlessly repeated, over and over… seeped into the material as direct prints, as ghost prints, traces, residues… stamp, stamp, stamp.

Thud.

The drop cloths absorb everything.

They collect information.

The material has no value. It is the unseen.

It carries the words of someone who was also unseen.

If you or someone you know is in crisis or experiencing suicidal thoughts, help is available at all times. Call or text 9-8-8 anywhere in Canada, or 1-866-APPELLE (1-866-277-3553) in Quebec to reach a suicide crisis helpline. A suicide prevention counselor is there for you 24/7.

Swapnaa Tamhane’s art practice is dedicated to the material histories of cotton and jute, which led to making handmade paper, archival research, and textile installations. She collaborates closely with artisans in Kutch, Gujarat, India, in a skill-sharing process. Tamhane holds an MFA in Fibres & Material Practices from Concordia University, Montreal. Past exhibitions have been held at Nature Morte, Delhi; articule, Montreal; Sculpture Park, Jaipur; Green Art Gallery, Dubai; Victoria & Albert Museum, Dundee, Scotland; with solo exhibitions at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and Surrey Art Gallery, Surrey. Upcoming exhibitions will be held at the Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts, and The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles.

The artist wishes to thank Salemamad Khatri, Abdulaziz Khatri, Aman Sandhu, Julia Eilers Smith, and Pip Day.