A gap always manifests itself between the publication of a text in one language and that of its translation, or between the inaugural presentation of an artwork in one context and its display in a second.

In this project, presented in two installments curator Vincent Bonin addresses a manifestation of this phenomenon of deferred reception: the way in which a body of theoretical texts by French philosophers was assimilated in Anglophone art milieus from the late 1970s to the present. However, Bonin maps this trajectory of “French Theory” in an indexical way by alluding to the communities of elective affinities formed by artists, critics and curators during the parenthesis of postmodernism (1977-1990).

D’un discours is divided into five groupings that correspond to the five exhibition areas of the gallery. They are connected together so as to emphasize the already existing links between the protagonists rather than arbitrary spatial or thematic cohabitation.

EXPLORE

- Identity and its construction through language;

- Notions of translation, translatability, and culture, and the ways in which these come into play in this exhibition;

- Translation relates to the curatorial notion of a group exhibition;

- Conventions of exhibition and visual display and how they are questioned and addressed here;

- Visual pleasure;

- The relationships that this exhibition builds between sound, image, and text;

- The various types of documents that are included here and their status in the exhibition;

- How one reads this exhibition; the role played by narrative, how it develops and unfolds;

- French Theory and how it is represented in this exhibition;

- Political concerns and perspectives, their presence here and their representation;

- History, the role that it plays in this exhibition and the means by which it is activated through documents and artworks;

- The ways in which historical and contemporary works interface in the exhibition;

- The curatorial point of view that is expressed in this exhibition.

Produced with the support of the Frederick and Mary Kay Lowy Art Education Fund.

This exhibition is made possible by the Canada Council for the Arts.

Berwick Street Collective, Andrea Fraser, Jean-Luc Godard, Group Material, Peter Halley, International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa, Gareth James, Mary Kelly, Karen Knorr, Jon Knowles, Duane Lunden, Thérèse Mastroiacovo, Anthony McCall, Anne-Marie Miéville, Philip Monk, Laura Mulvey, Claire Pajaczkowska, Jeff Preiss, Yvonne Rainer, Andrew Tyndall, Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, Jane Weinstock, Peter Wollen

Presented in collaboration with Dazibao

Curator: Vincent Bonin

THE CURATOR

Vincent Bonin is an author and independent curator. From 2000 to 2007, he worked as an archivist at the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology (Montreal). As a curator, he notably organized the three-part project (consisting of two exhibitions and one publication) entitled Documentary Protocols (1967-1975) at Concordia University’s Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery (2007-2008) and, with Catherine Morris, Materializing “Six Years”: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art (2012-13) at the Brooklyn Museum. The accompanying publication, edited by Bonin and Morris, was published by MIT Press. Besides his research on conceptual art practices of the 1960s and 1970s, Bonin is interested in the social meaning of archives, and the refashioning of the documentary genre in the field of contemporary art.

CloseTHE EXHIBITION

Jon Knowles, Left foot, 2013

Paint on orthopaedic body splint, nails

Courtesy of the artist, Montreal

Jon Knowles, Alice, 2013

Inkjet print on canvas

Courtesy of the artist, Montreal

Ian Wallace, For an Ethic of Ambiguity, 1969

Collage on paper, 4 pages

Courtesy of the artist, Vancouver

Ian Wallace, Untitled (In the Studio with Table), 1969/1992

Gelatin silver gelatin print

Collection of Moshe Mastai, Vancouver

Duane Lunden, Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace, Free Media Bulletin 1, 1969

Mimeographed pages, envelope

Courtesy of Ian Wallace, Vancouver

Ian Wallace, Image/Text, 1979

Video transferred to DVD, 29 min 12 sec, colour, silent

Courtesy of the artist, Vancouver

Thérèse Mastroiacovo, Art Now, 2005

Graphite on paper

Art Now (Now Appearing, 1996), 2013

Art Now (The situation now: a survey of local non-objective art, 1995), 2013

Art Now (Living Here Now – Art & Politics, 1999), 2013

Art Now (Feminism now: theory and practice, 1985), 2013

Art Now (Now see here! : art, language and translation, 1990), 2013

Art Now (Everybody now: the crowd in contemporary art, 2001), 2013

Art Now (As of Now, 1983), 2013

Art Now (Signs of change: social movement cultures, 1960s to now, 2010), 2013

Art Now (Strategies of survival-now! : a global perspective on ethnicity, body and breakdown of artistic systems, 1995), 2013

Art Now (Environments Here and Now, 1985), 2013

Courtesy of the artist, Montreal

In 2012, the Gallery acquired 10 drawings from this series which were presented in the exhibition Interactions, curated by Mélanie Rainville the same year (August 30 – October 27). The drawings shown here are hung in Room A at the same location as those presented in Interactions.

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Part II (analysed utterances and related speech events), 1975 Letterpress text on paper and inked rubber type; typed text on index card (23 panels); electrostatic printing on paper (2 panels); black and white photograph (1 panel)

Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift of the Junior Committee Fund, 1987

Mary Kelly, Room H-110, Hall Building, Concordia University, 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West, Montreal, December 9, 1988

Sound recording, 73 min 21 sec

Conference organized by Gail Bourgeois for La Centrale, Powerhouse Gallery, in collaboration with the Committee on the Status of Women, Concordia University. The recording was made by Bourgeois, who also wrote Mary Kelly’s biography and read it before the lecture. The sound recording is in Concordia University’s Records Management and Archives, Montreal

Mary Kelly, Interim Part 1: Corpus

Poster for the exhibition at Powerhouse Gallery, Montreal, November 26 – December 18, 1988. Fonds La Centrale, Records Management and Archives, Concordia University, Montreal

Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, Riddles of the Sphinx, 1977

16 mm film transferred to DVD, 91 min

Distributed by the British Film Institute, London

Yvonne Rainer, The Man Who Envied Women, 1985

16 mm film transferred to DVD, 125 min

Distributed by Zeitgeist Films, New York

Peter Halley, Prison, 1987. Vacuum formed plastic with silkscreen, 4/18

Sonnabend Collection, New York

This limited edition print was produced and sold by Editions Ilene Kurtz, New York, in 1987

“In the context of conceptualism’s resistance to a theory of subjectivity, I argued that if medium comprised not only a physical support, but also a technical one with a set of procedures or rules, then in my case, the rules were generated by a method in which material indexicality was the privileged means of translating psychical affects into form.”

Mary Kelly, “On Fidelity: Art, Politics, Passion and Event,” Feminism is Still Our Name: Seven Essays on Historiography and Curatorial Practices, ed. Malin Hedlin Hayden and Jessica Sjoholm Skrubbe (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010) p. 5.

In a 2010 interview, Ian Wallace distinguished between a structuralist (late 1960s) and a semiotic (1970s) period in his practice; each of the works sampled here can be seen as an object of transition linking those two periods.1 Wallace published Free Media Bulletin No. 1 in 1969 with Duane Lunden and Jeff Wall, using Intermedia Society’s printing facilities.2 The periodical contained a sampling of articles that constituted a referential field common to the three artists.3 Brought together in this way, the texts acquired the status of quasi-readymades. Formally, Free Media Bulletin can be compared with publications produced around the same time in Vancouver with an assemblage or collage approach. In terms of content, however, it is distinct from them: not only were Lunden, Wall and Wallace moving away from the utopias of Fluxus and Conceptualism, but they were also conscious at the time of the added value conferred to information by the fact of its circulation.

With For an Ethic of Ambiguity (1969), Wallace pursued his interest in the interfacing of the dissemination of discourse and the material instances of its enunciation, using a wine glass to cut out circles from the centres of pages of Simone de Beauvoir’s essay Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté (1947). Thus part of the text on page 146 is surrounded by text from page 145, and so on. The collage procedure created a zone of incompleteness, interrupting the continuity of both the reading of the text and the visual experience of the pages. Ten years later, in 1979, Wallace extrapolated the layout for Image/text from the graphical structure of Stéphane Mallarmé’s book Un coup de dé jamais n’abolira le hasard (“A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance,” 1897). Initially conceived of as alternating colour and black & white photographic panels, Image/text was also “animated” in video format, as shots proposing a “model” for the image sequence.4

In the community made up of Mary Kelly and her activist, filmmaker and theoretician peers, Jacques Lacan’s rereading of Freud was key to moving beyond essentialist first-wave feminism.5 When the artist began Post-Partum Document in 1973, only the Rome lecture of 1953 entitled “The Function and Field of Speech in Psychoanalysis,” a translation by Vancouver-based Anthony Wilden, was available to readers of English.6 In her introduction to the published version of Post-Partum Document, Kelly explains that by the time she had completed parts 1, 2 and 3 of the work in 1976, the process of translating and interpreting Lacan was well under way: “The Patriarchy Conference in London that same year clearly indicated that the debate had shifted from the terms of sexual division to the question of sexual difference. Some readers will regard such formulations as ‘negative entry’ or ‘negative place’ with skepticism (or perhaps nostalgia?) but will recall the context and our first attempts to articulate a different relation to language (and to castration) for women without subscribing to the essentialist notions of a separate symbolic order altogether.”7

Before starting Post-Partum Document, Kelly had been a member of the Berwick Street Collective, which drew from the complex debates begun in 1970 around the rubrics of the documentary and structural cinema to make the Brechtian film Nightcleaners (Part 1) (1970–75).8 With Riddles of the Sphinx (1977), Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen also set about problematizing the dialectics between theory and practice to make visible the modes whereby patriarchal and capitalist structures were reproduced in the fabric of the film itself.9 While finishing the editing of Nightcleaners in 1975, Kelly created the installation Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry with Margaret Harrison and Kay Hunt (it was shown at the South London Art Gallery). In Post-Partum Document, Kelly continued that investigation of invisible labour, but this time structured her work around the simultaneity of three sequences of events: the mother’s experience of detachment, the child’s entry into the realm of the symbolic, and the production of an art work. Post-Partum Document comprises 135 elements that the artist produced in six stages between 1973 and 1979. For Part II: (analysed utterances and related speech events) (1975) Kelly recorded the voice of her son producing isolated sounds and words as simple “affirmative” or “negative” utterances. She continued the process over five months until the child began constructing simple sentences and self-identifying with his image (the Lacanian “mirror phase”). However, that analytical grid also emphasizes the irruptive quality of the mother’s desire as she attempts to respond to the child’s needs. The words were excerpted from the flow of speech, transcribed and often wrongly interpreted. More than any other component of Post-Partum…, the sequence of these 23 panels functions as an allegory for the translation operations required to experience an artwork, and which never manage to completely satisfy the viewer’s drive for knowledge.10

Each section of Post-Partum Document with the exception of the introduction has been acquired by a public museum. Part II (analysed utterances and related speech events) was added to the Art Gallery of Ontario collection in 1987 by Barbara Fischer, during her, Philip Monk’s and Roald Nasgaard’s tenures as contemporary art curators. Whenever it is shown in a new context, the work is usually the subject of a critical reassessment. In 1998, for example, all of its sections were gathered by Sabine Breitwieser for the Generali Foundation in Vienna, while Juli Carson curated a “supplement” with pieces from the artist’s archive, entitled “Excavating Post-Partum Document, Mary Kelly’s Archive 1968–1998.”11 For “D’un discours…” Post-Partum Document has been paired with a recording of the lecture Kelly gave at Concordia University on December 9, 1988, as well as the poster for her show Mary Kelly, Interim: Corpus 1 at Powerhouse Gallery.

In 1979, Anthony McCall, Claire Pajaczkowska, Andrew Tyndall, Jane Weinstock and Ivan Ward wrote Sigmund Freud’s Dora: A Case of Mistaken Identity, addressing the complexity involved in appropriating Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis as a means of magnifying feminist discourse.12 In the early 1970s, Yvonne Rainer abandoned choreography for filmmaking; her third feature-length work, The Man Who Envied Women (1985), elucidated the paradox of theory as a tool for legitimization and social veneer in the discourse of certain leftists at a time when artists were being forced out of the industrial spaces that they had helped repurpose.

Peter Halley’s work proceeded from an entirely different reading of theory, but also showed his desire to acknowledge a paradigm shift in the production of art during the same period. In June 1984, his “The Crisis in Geometry” appeared in Arts Magazine, pointing to a redefinition of abstraction between the 1970s and the following decade: “Since 1980, another generation of geometric work has appeared for which the relevant text is not so much [Michel] Foucault as it is [Jean] Baudrillard. This generation of artists is no longer connected to an industrial experience (compare [Richard] Serra’s insistence on his background working in steel mills or [Alice] Aycock’s use of construction-site lumber). Rather, this group of artists is the product of a post-industrial environment where the experience is not of factories but of subdivisions, not of production but of consumption.”13

____________________

1See “Then and Now and Art and Politics: Ian Wallace interviewed by Renske Jansen,” Ian Wallace: A Literature of Images, ex. cat., Vanessa Joan Müller, Beatrix Ruf and Witte de With, eds. (Berlin and New York: Sternberg Press, 2008).

2In the 1960s Wallace taught at the University of British Columbia, where his students included Duane Lunden, Rodney Graham and Jeff Wall. He later taught alongside Wall at Simon Fraser University, and still later, at the Vancouver School of Art (now the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design). Roy Arden, Stan Douglas and Ken Lum were also his students.

3The Free Media Bulletin included, among others, Marcel Duchamp’s “Notes sur le readymade,” reproduced from his boîte verte, a text by Richard Huelsenbeck assessing the contemporaneousness of Dadaism, plus excerpts from essays by Ad Reinhart and the Situationist Alexander Trocchi.

4In this video, Wallace is also seen in his studio, echoing the photograph Untitled (In the Studio with Table), which he made in 1969.

5See the translations of Lacan by Jacqueline Rose published as Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and the École Freudienne, ed. Juliet Mitchell and Jacqueline Rose (New York: Norton, 1983).

6Jacques Lacan, The language of the self; the function of language in psychoanalysis, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1968. Published in French under the title : « Fonction et champ de la parole et du langage en psychanalyse », La psychanalyse, vol. I (Paris: 1956).

7Mary Kelly, “Foreword,” Post-Partum Document (Berkeley: University of California Press, Vienna: Generali Foundation, 1999) xxiii. The theoretical sources of Post-Partum Document are listed in the section “References,” 196–97. Each of the works or articles is indexed to one or several sections of the work.

8In England, these protagonists were especially prominent in the pages of the journal Screen, founded with the aim of expanding the scope of analysis of Hollywoodian narrative, while liquidating the prevalence of the author, and proposing a model for political experimental cinema.

9One of Mulvey and Wollen’s interlocutors was Mary Kelly, appearing along with her work Post-Partum Document in one of the film’s long, unbroken sequences.

10The last panel of each section subverts Ferdinand de Saussure’s schema, replacing the signifier with a question (in this case, “Why Don’t I Understand?”).

11See Juli Carson, “Re-viewing Post-partum document,” Documents 13 (1998) and, more recently, Eve Meltzer, “Something at once lost, forgotten, remembered and hoped for. ‘e’ as in ‘me’- Mary Kelly, ‘Documentation VI’ (1978), Post-Partum Document,” in Systems We Have Loved: Conceptual Art, Affect, and the Antihumanist Turn, ed. Eve Meltzer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

12Both Riddles of the Sphinx and Dora: A Case of Mistaken Identity were part of a program of film screenings in conjunction with the exhibition Difference: On Representation and Sexuality, curated by Kate Linker and Jane Weinstock at the New Museum (8 December 1984 -10 February 1985) and the Renaissance Society (3 March 3 – 21 April 1985), in which two sections of Post-Partum Document were also shown.

13Peter Halley, “The Crisis in Geometry,” Arts Magazine 58: 10 (1984).

Views of the exhibition, Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) organized by Group Material (Julie Ault, Doug Ashford, Tim Rollins), White Columns, New York, 6 – 28 February, 1987.

4 digital prints. Group Material Archive, Downtown Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, New York

Courtesy of Julie Ault, New York

Namibia in Struggle : Portable Exhibition of Photographs, circulated by The International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa, London, 1987

Presented in the exhibition Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard)

This copy is now in the Group Material Archive, Downtown Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, New York

Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, Six fois deux, sur et sous la communication, épisode 6A, « Avant et après », Co-produced by the Institut national de l’audiovisuel, Sonimage, 1976, 56 min. 12 sec.

The series was broadcast in France by FR3, between July and August 1976, two episodes per week at 8:30 pm. The series was presented in the exhibition Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard)

“Anti-Baudrillard,” File Megazine

No. 28 (1987), unpaginated

Courtesy of Vincent Bonin, Montreal

“A theoretical jungle surrounds us. Overgrown form inactivity, this jungle harbors real dangers – the dissolution of history, the disfiguration of any alternative actuality, and the attempt to disown practice. Activism is perceived as illusory in an illusory culture. In this self-imposed confinement, art becomes comfortable, criticality becomes style, politics becomes idealism, and ultimately, information becomes impossibility. Group Material refutes this operatively submissive philosophy with this proposed exhibition, Anti-Baudrillard (Resistance)”

Excerpted from the artists’ statement, written October 1986. Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) would be held at the White Columns art space from 7 to 28 February, 1987.1 Doug Ashford, Julie Ault and Rollins formed Group Material at the time the show was organized.

The collaborative was formed in 1979 around its members’ common interests in feminist discourse, the civil rights movement, and Marxist theory, as well as their membership in an informal network of collectives, alternative spaces and periodicals in the orbit of the New York City nonprofit arts community. Before dissolving the group in 1996, the members created urban as well as media interventions (posters, advertising inserts) simultaneously with themed exhibitions. The all-over hanging style of the shows saw works of established and less well-known artists paired with artefacts/objects and various documents. Doug Ashford would later describe that eclecticism: “Abstract paintings occupied space defined by popular insurgency, children’s drawings sat alongside electoral advertisements next to paintings of heads of state …, institutional critique was overtaken by “easy listening” versions of 60s ballads and so on.”2 In 1982, for the exhibition Primer (for Raymond Williams), the collaborative adapted the terminological lexicon posited by Williams in Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (1976) to a new framework in an attempt to present contemporary art and pop culture side by side.

Once again problematizing the dialectics of theory and practice, Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) aimed to put forward a counter-example to what was understood at the time as the nihilist recycling of Jean Baudrillard’s theories by Peter Halley and other protagonists of the artworld. For the show, Group Material assembled under the same banner works by representatives of their like-minded community, which they claimed provided undeniable proof of a “political reality”3 contra the logic of simulacra. The issues in play encompassed the full spectrum of circumstances previously condemned by the collaborative: U.S. imperialism in South America, Apartheid, and so on. Moreover, Rollins, Ashford and Ault engaged in an archeology of agit-prop, showing reproductions of key works of historical avant-gardes. Group Material, however, did not completely pit the theoretical camps against one another. Rather, they encouraged ambivalent stances toward Baudrillard and, by extension, resistance. In her contribution, ‘Resistance’ Or Why I Am Not ‘Anti-Baudrillard’, Barbara Kruger quoted a text by the philosopher in which he listed the flaws of antinomic reasoning.4 Group Material also organized a complementary closed-door panel discussion comprising artists Judith Barry, Peter Halley, Oliver Wasow, Julie Wachtel and critic William Olander, who debated in more specific terms their complex relationships to Baudrillard (Barry said hers was “like a bad love affair”). Group Material then distributed a small publication on the premises that included an abridged version of the panel discussion. A few months later, the Canadian collective General Idea published the same text in Issue 28 of FILE Megazine, which brought together interventions by artists who at the time were using “the language and the subject of commodification as the canvas upon which they layer their artworks.”5 Except for a few multiples (including Untitled, 1991) shown sporadically,6 and apart from its critical reception,7 the works of Group Material are now confined to the extant material traces of their projects in the Fales Library at New York University, and some “past exhibitions” archives of institutions that hosted them, such as White Columns.8 At the Fales, the Resistance exhibition file includes views of the installation and prospective lists of works that reveal the members’ deliberations toward a consensus. It also includes research materials, copy-edited and proofread copies of the panel discussion transcription, correspondence with artists and critics, as well as the publication Namibia in Struggle: Portable Exhibition of Photographs.

I invited Julie Ault to re-activate Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) as part of D’un discours…, in the hope that she would expand upon the description of the exhibition in the chronology included in her book Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material. She did not decline, but suggested that I produce my own fragmentary cross-section of the event—issuing the caveat that I forgo any attempt at reconstitution. As she explained in a text about ulterior lives for Group Material: “When the group ended in 1996, I was intent on preserving its ephemerality, resisting becoming history, and opposed to leaving the responsibility of defining and interpreting our work – at least initially – to a curator or art historian … A great deal of interest in Group Material has been expressed in the years since it ended. Would it continue if the combination of fragmentary access and an amorphous status, which invite projection, were offset by the concrete and intrinsically conservative forms of archive and book?”… Contexts cannot be replicated. It is impossible to reproduce the climate of circumstance and perception and understanding for events …”9

____________________

1Julie Ault, “Chronicle: 1979 – 1996,” in Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material, ed. Julie Ault (London: Four Corners Books, 2010), 119.

2Doug Ashford, “An Artwork is a Person,” in Ault, 223.

3Conrad Atkinson, Bruce Barber, Gretchen Bender, Joseph Beuys, Honoré Daumier, Peter Dunn, Andrea Evans, Madge Gill, Mike Glier, Leon Golub, George Grosz, Hans Haacke, Edgar Heap of Birds, John Heartfield, Janet Henry, Jenny Holzer, Oskar Kokoschka, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Lorraine Leeson, Susan Meisales, Brad Melamed, Gerhard Merz, Michael Nedjar, Odilon Redon, Nancy Spero, Carol Squiers, Gaston Ugalde, Carrie Mae Weems, Krysztof Wodiczko and Martin Wong. Video programming screened on three monitors included works by Dara Birnbaum, Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, and David Cronenberg.

4Excerpts of a transcription of Baudrillard’s text that Barbara Kruger quoted in her work ‘Resistance’ Or Why I Am Not ‘Anti-Baudrillard’, 1987 (original sourced text unknown): “It is always a question of proving the real by the imaginary, proving truth by scandal, proving the law by transgression, proving work by the strike, proving the system by crisis and capital by revolution, as for that matter proving ethnology by the dispossession of the object… without counting; proving theatre by anti-theatre, proving art by anti-art … Every form of power, every situation speaks of itself by denial, in order to attempt to escape, by simulation of death, its real agony …To seek new blood in its own death, to renew the cycle by the mirror of crisis, negativity and anti-power: this is the only alibi of every power, of every institution attempting to break the vicious circle of its irresponsibility and its fundamental non-existence, of its déjà-vu and its déjà-mort.”

5General Idea, “Editorial,” FILE Megazine 28 (1987), 8.

6In the exhibition This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s, curated by Helen Mollesworth, Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago, February 11–June 3, 2012.

7For an exhaustive critical discussion of Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard), see John Miller, “Jean Baudrillard and His Discontents,” Artscribe International 63 (1987), 48–51.

8For instance, a part of the Resistance (Anti-Baudrillard) archives may be viewed in digitized form on the White Columns website at: http://www.whitecolumns.org/archive/index.php/Detail/Occurrence/Show/occurrence_id/21

9Julie Ault, “Case Reopened: Group Material,” in Ault, 211–12.

Jon Knowles, Lulu, 2013

Inkjet print on canvas, nails

Courtesy of the artist, Montreal

“Description/Interpretation/Judgement. What is criticism? Parachute Discussions,” held as part of the symposium Art and Criticism in the Eighties, Ontario College of Art, March 17 and 18, 1984 (excerpt from the March 18 discussion period)

Digitized audiocassette, 50 min 40 sec

Parachute: revue d’art contemporain. Fonds, Archives Nationales du Québec, Montréal, gift of Chantal Pontbriand

In this excerpt, the voices heard are, in order, those of artist Bruce Barber, critics René Payant, Thierry de Duve, Philip Monk, Johanne Lamoureux and Craig Owens, and artist John Scott

Parachute art contemporain / contemporary art

Nos. 32 (September, October, November 1983), 42 (March, April, May 1986) and 48 (September, October, November 1987)

Courtesy of Vincent Bonin, Montreal

Views of the exhibition Magnificent Obsession organized by Mark Lewis and Geoff Miles; inaugural presentation at Artculture Resource Centre, Toronto, 20 May – 8 June, 1985

Also presented at Galerie Optica, Montreal, 19 October – 16 November, 1985. Participating artists: Karen Knorr, Mark Lewis, Geoff Miles, Olivier Richon and Mitra Tabrizian

The seven digitized images projected as part of D’un discours… were produced from the 35mm slides in the exhibition file in the Optica fonds, Records Management and Archives, Concordia University

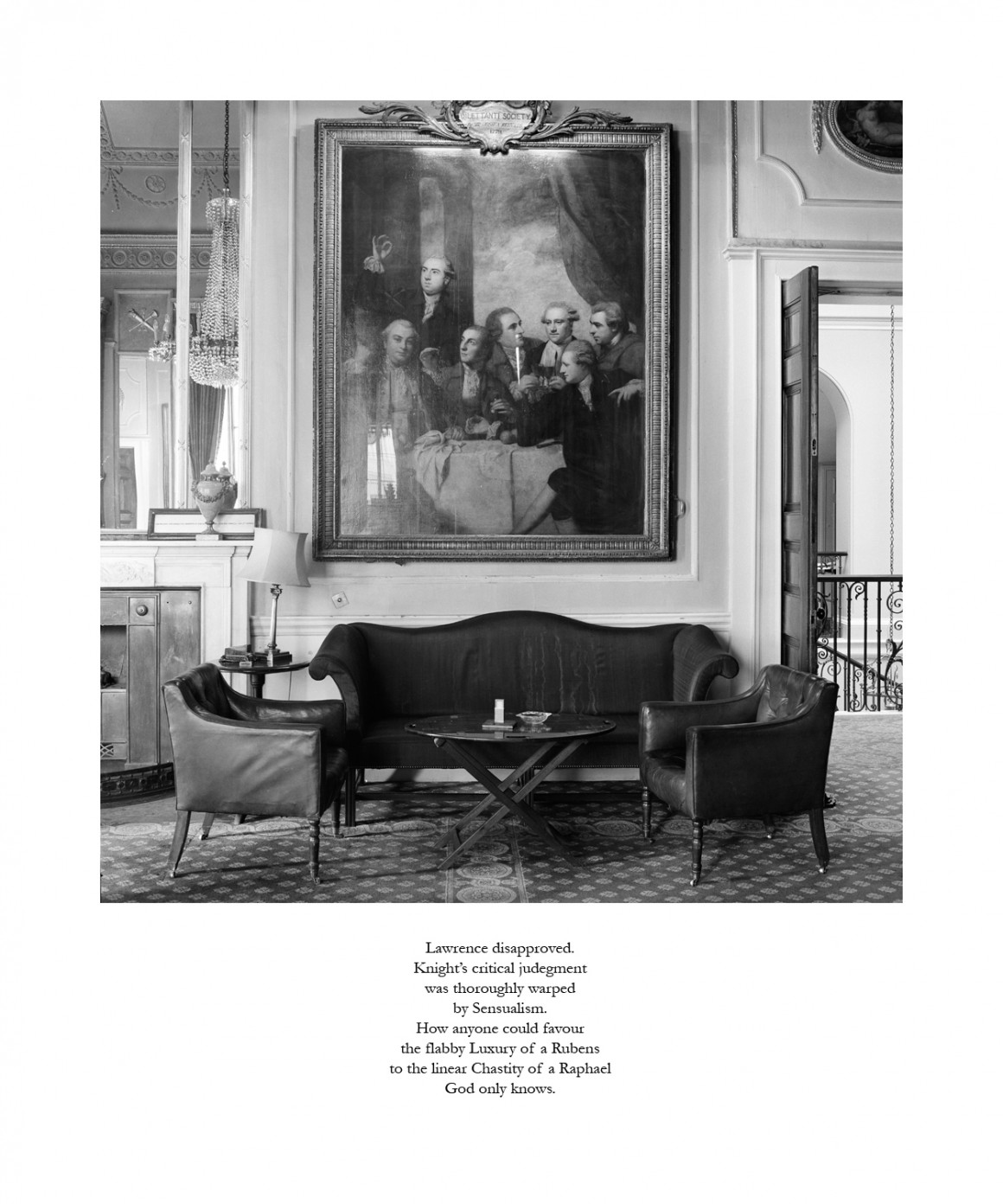

Karen Knorr, Gentlemen, 1983–1985

Six digital exhibition prints from scanned files of the 35mm negatives

Original prints shown as part of Magnificent Obsession, Artculture Resource Centre, Toronto, May 20 – June 8, 1985

Also presented at Galerie Optica, Montreal, 19 October – 16 November, 1985. Copies produced in Montreal by Photosynthèse with the kind permission of the artist, London

Philip Monk, Reception French Theory: Toronto, Montreal, November 14, 2013

37 min 54 sec

Produced by the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery

Video and editing: Deborah VanSlet

Phillip Monk, Peripheral Drift, A Vocabulary of Theoretical Criticism (Toronto: Rumour, 1979)

Courtesy of Artexte, Gift of René Payant, Montreal

Monk had sent Peripheral Drift… to Montreal art critic René Payant. In 1987, Payant donated the exhibition catalogues in his personal library to Artexte Documentation Centre, and bequeathed the theoretical works in his collection (works on semiotics, aesthetics, philosophy and literary theory) to the Bibliothèque des sciences humaines et sociales, Pavillon Samuel-Bronfman, Université de Montréal.

“Yes, you have my permission to photocopy the pamphlet. … I pulled out a copy from my storage the other day … It was published by Rumour Publications, which was run by Judith Doyle … I think Rumour published only a few titles, but one (more of a book) was by Kathy Acker. The text [of Peripheral Drift] came out of my dissatisfaction with traditional art criticism and it presaged some of my other performative texts, that we then called “theoretical fictions,” that are as the first part of my Struggles with the Image book. The sources or influences are obvious. There’s a complementary piece that was published in Only Paper Today that continues the Anti-Oedipus strain [of Peripheral Drift]—a fictional self-interview (“Theoretical Dance: This Body is in Creation,” Only Paper Today 6:8 (October 1979), p. 18.). Also some of the ideas of Peripheral/Drift were published as applied to parallel gallery structures as “Terminal Gallery/Peripheral Drift,” Spaces by Artists/Places des artistes, Toronto: ANNPAC, 1979, 32–35.”

Philip Monk, excerpts from an e-mail message to Michèle Thériault, 18 October, 2013

In the early 1980s the Montreal-based periodical Parachute1 was notable for fostering the integration into English Canadian intellectual circles of theoretical discourse by francophone thinkers, while also offering unpublished articles in the latter language (often by Quebec authors).2 These texts born of entirely different contexts appeared alongside each other, suggesting to the reader uncommon transitings between, for example, Jeff Wall’s interest in Édouard Manet and Georges Didi-Huberman’s research into Jean-Martin Charcot’s iconography of hysteria.3 In return, the symposia organized by the journal’s editors allowed contributors to meet face-to-face and point out kinships, align complementary thinking, or elicit dissensions.4 Moreover, the English-language content in issues of this period occasionally foreshadowed the currents of “French Theory” that, in subsequent years, were to filter through the writings of various protagonists on the New York and London art scenes. In Issue 32 (Fall 1983), for example, Kate Linker contributed an essay that laid the foundations of the exhibition On Difference: Representation and Sexuality, which she co-curated with Jane Weinstock at the New Museum in 1985.5 During this time, while Parachute was cutting-edge, few exhibitions in Canada gave consideration to this hybridization of second-wave feminist discourse and the concept of representation.

In 1985, Magnificent Obsession was to bridge that gap, in part. Organized by Mark Lewis and Geoff Miles at the Artculture Resource Centre, Toronto, and subsequently presented at Optica, an artist-run centre in Montreal, the exhibition featured their works alongside those of their classmates Karen Knorr, Olivier Richon and Mitra Tabrizian. The five met in Victor Burgin’s course at the Polytechnic of Central London (now the University of Westminster). At the time Burgin was mostly teaching photography, but included in his curriculum texts by Roland Barthes, Louis Althusser and Jacques Lacan, along with articles from the periodicals New Left Review and Screen. Theoretician and filmmaker Laura Mulvey, a frequent contributor to Screen, wrote the catalogue essay for Magnificent Obsession, which was also published in Issue 42 of Parachute. In it she commented on the complex relations among Lewis, Miles, Knorr, Richon, Tabrizian and the like-minded community of artists that had come together during the 1970s (Burgin, her collaborator and partner Peter Wollen and Mary Kelly, among others): “These photographs are the work of a next generation, no longer strictly bound by the confrontational aesthetics of the 1970s. The formal influences are there, there is a continuity of interest and concern but there are important and marked differences, particularly with respect to realism and pleasure. It is as though the long, hard battle against the transparency of realism and the spectator pleasure inscribed by tradition and convention (of which the use of woman’s image is emblematic) has broken down and reached the end of the road. Out of the debris a language and imagery can emerge that is no longer primarily concerned with an either/or dichotomy. But there is no spirit of compromise nor even synthesis here. The values and desires of this group have developed out of the process of working their original influences through, to the point of distance and displacement where ‘pleasure’ and ‘realism’ are material for irony and play.”6

In 1986, Lewis founded the Toronto collective Public Access with Christine Davis, Janine Marchessault and Andrew Payne. In Issue 48 of Parachute, they published a quasi-manifesto, advocating for a new model of artistic intervention based on the concepts of public space and democracy, without circumventing the problem of “the institutionalization of conflict.”7 An expanded version of that text appeared in the catalogue to the exhibition Some Uncertain Signs, organized the same year by the group, which was also the first issue of their journal Public. Relying on the exceptional accessibility of an electronic bulletin board system in downtown Toronto, Lewis, Davis, Marchessault and Payne asked 22 contributors to supply statements. The initial polysemic quality of these was exacerbated by their circulation via the then-novel device of the BBS, as the anonymity of the submissions disengaged them from the proper name that, de facto, engenders the exchange value of a work.8

____________________

1The journal was founded by Chantal Pontbriand and France Morin in 1975. Its last issue (No. 125) appeared in January 2007. There are two anthologies edited by Pontbriand containing a sampling of texts: Parachute: Essais choisis (Paris: La Lettre Volée, 2000) in French, and Parachute: The Anthology, Vol. 1 (Zurich: JRP-Ringier, 2012), in English. From 1983 to 1987, the editorial committee included (on a rotating basis depending on the content of a given issue) Serge Bérard, Robert Graham, Bruce Greenville, Johanne Lamoureux, Martine Meilleur, Philip Monk, Jean Papineau, René Payant, Richard Rhodes and Thérèse St-Gelais.

2At the time, Serge Bérard, Gervais, Lamoureux, Papineau, Payant and Christine Ross wrote frequently for the journal.

3Jeff Wall, “Unity and Fragmentation in Manet,” Parachute 35 (1984), 5–7; George Didi-Huberman, “Une notion du ‘corps-cliché’ au XIX siècle,” ibid., 8–14. In 1979, the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard was commissioned by the government of Quebec to write a report on knowledge and information society for the Royal Commission of Inquiry on Education in the Province of Quebec (http://www.cse.gouv.qc.ca/fichiers/documents/publications/ConseilUniversite/56-1014.pdf). Later that same year, another version of the text was published by les Éditions de Minuit under the title La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir. The report didn’t have much impact in Quebec’s intellectual communities at the time, just as the book had a rather timid reception in France. However, it reached broader audiences when it was translated in English by Geoffrey Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984, with a foreword by Fredric Jameson).

4These included Performance : postmodernisme et multidisciplinarité at Université du Québec à Montréal, 1980, and Discussions : Art and Criticism in the Eighties at the Ontario College of Art, 1984.

5Kate Linker, “Representation and Sexuality,” Parachute 32 (1983), 12–23. The New Museum was the first venue to host Difference: On Representation and Sexuality (December 8, 1984–February 10, 1985); the exhibition was subsequently presented at the Renaissance Society, Chicago (March 3–April 21, 1985). For the exhibition documentation at the New Museum, see: http://archive.newmuseum.org/index.php/Detail/Occurrence/Show/occurrence_id/97. For the Renaissance Society, see: http://www.renaissancesociety.org/site/Exhibitions/Intro.Difference-On-Representation-and-Sexuality.95.html

6Laura Mulvey, “Magnificent Obsession,” Parachute 42 (1986), 7.

7They were here citing Claude Lefort. See Public Access Collective, “Public Imaginary,” Parachute 48 (1987), 21–25.

8The exhibition included contributions by, among others, Don Carr, Michael Cartmell, Christine Davis, Ann Delson, Lynne Fernie, Charles Gagnon, Mary Kelly, Robert Kennedy, Barbara Kruger, Mark Lewis, Less Levine, Janine Marchessault, Murray Pomerance, Michael Snow, David Tomas, Peter Wollen. See Mark Glassman’s review, “Some Uncertain Signs,” Parachute 45 (1986–87), 35–36.

Jon Knowles, Right Hand, 2013

Paint on orthopedic body splint

Courtesy of the artist, Montreal

Gareth James, Untitled Stolen Bicycle, 2008

Bicycle frame, chain joint, glass, inkjet photographic print

Initial presentation: “The Real is that which always comes back to the same place Broadway between 101st and 102nd Streets, New York, NY 10025, March 21, 2008,” Christian Nagel Gallery, Cologne, 31 May – 28 June, 2008

Collection of Norah and Norman Stone, San Francisco

Gareth James, The Screwunscrew, 2009

Monofilament, bicycle inner tubes, steel and brass screw

Initial presentation: As Yet Untitled / When a Financial Institution Collapses There Is No Spectacular Outpouring of Gold / Glass Transition Temperature. Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, 23 May – 27 June, 2009

Collection of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner, New York

Gareth James, Lui, 2009

Graphite on inkjet print on canvas with bicycle inner tube

Initial presentation: As Yet Untitled / When a Financial Institution Collapses There Is No Spectacular Outpouring of Gold / Glass Transition Temperature. Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, 23 May – 27 June, 2009

Courtesy of the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Gareth James, Untitled (Charles de Gaulle, Dress Uniform with Black to White Spiral), 2011

Chromogenic print

Initial presentation: Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 22 October, 2011 – 15 January, 2012

Collection of Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner, New York

Gareth James, Elle, 2011

Chalkboard paint on wood, powder coated handmade brass screw

Initial presentation: Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 22 October, 2011 – 15 January, 2012

Courtesy of the artist and of Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Gareth James, Untitled (Young Claude Levi-Strauss with Monkey, Fragment Spirals), 2011

Chromogenic print

Initial presentation: Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 22 October, 2011 – 15 January, 2012

Courtesy of the artist and of Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Gareth James, Untitled (Edward Curtis, Black to White Spiral), 2011

Chromogenic print

Initial presentation: Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, 22 October, 2011 – 15 January, 2012

Courtesy of the artist and of Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

Gareth James, Untitled (Edward Curtis with Black Irregular Circle), 2011

Chromogenic print

Initial presentation: Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, 22 October, 2011 – 15 January, 2012

Courtesy of the artist and of Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

“Transformation masks never reveal the face that is masked. In addition, they are not adapted to the face, do not follow its features, are not made to conceal it. They open and close only onto other masks … Their existence consists in the hinge that links them at their centre.”

Catherine Malabou. La plasticité au soir de l’écriture : dialectique, destruction, déconstruction, Paris: Éditions Léo Scheer, 2005, p.14 (our translation).

Gareth James was born in the United Kingdom. He left London in 1997 and settled in New York City, enrolling in the Independent Study Program of the Whitney Museum. In 2001, under the borrowed identity of curator and colour theoretician Storm Van Helsing, he organized an anti-exhibition, wRECONSTRUCTION, at the American Fine Arts Co. Gallery.1 The space was inaccessible to the public throughout the event while James programmed behind-closed-doors meetings among handpicked individuals, Colin de Land (director of American Fine Arts Co.), and Van Helsing. After de Land’s death and the closing of his gallery, James co-founded a co-operative space called Orchard in the Lower East Side, the lifespan of which (2005–2008) was predetermined by its members.2 Since 2010, he has been an assistant professor in the Department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory at the University of British Columbia.3 Gareth James is represented by Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York City.4

The sampling of works in Room D is an attempt to distil the contents of three linked monographic exhibitions by James held between 2008 and 2011. Although no object was on view more than once, elements of the first show appeared in the second, and a portion of the second was repeated in the third. On March 21, 2008, James stole a bicycle in New York City and then showed it in Cologne (The Real is that which always comes back to the same place: Broadway between 101st and 102nd Streets, New York, NY 10025, March 21, 2008, Galerie Christian Nagel, Köln, May 31–June 28, 2008). Two photographic prints served as indices of the occurrence of the action, though they did not depict it: the first showed the site before the crime; the second, the storefront of the locksmith’s where the artist purchased the equipment used to break the bicycle lock.5 Since bought by collectors Norah and Norman Stone, the bicycle is being exhibited here for the first time in public since 2008 thanks to their generosity (they defrayed the cost of shipping it from Oakland to Montreal and back). Despite this relative mobility of the concrete object, the initial, specific, abstract situation of property infringement “always/still comes back to its place” to haunt the new circumstance. To define the scope of his concept of interpellation, Louis Althusser offered the example of a passerby who turns around when hailed by the police (“Hey, you there!”). Contrary to the readymade, the existence of which depends on post facto recognition of its artistic status, the stolen bicycle implicates in the crime, a priori, all those who reiterate its added symbolic value while denying its legal standing.6 The second exhibition (As Yet Untitled / When a Financial Institution Collapses There Is No Spectacular Outpouring of Gold / Glass Transition Temperature, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, May 23 – June 27, 2009) fills the gaps left by the first. Evoking the bicycle’s wheels, the inner tubes bear the engram of the thief but, once they are perceived as containers, are free of him and have become a sculptural substrate.

On the cover of the French edition of Althusser’s memoirs L’avenir dure longtemps (begun in 1985, published in 1992) is a 1978 photograph by Jacques Pavlovsky of the philosopher standing at a blackboard, about to complete a diagram. The impossibility of locating sources allowing for interpretation here sets in motion the full range of material and conceptual transformation operations at the centre of As Yet Untitled. Lacking this information, James therefore fails to fulfil the role assigned to him as the artist or the “subject supposed to know” through which “all meanings ought to pass.”7 James then engages in a systematic analysis of the texts written by the philosopher while developing the diagram at the École normale supérieure in Paris. From this research, he extrapolated the content of the third exhibition (Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, October 22, 2011 – January 15, 2012), aiming to forge a context for the image lacking a code.8 Other protagonists emerge here, in the form of photographic portraits that carry along episodes in structuralism’s history mingled with the colonialist past of France and North America. Each one’s face is hidden by a spiralling superimposition of Althusser’s diagram, shifting to either black or white. The referential constellations thus constituted are augmented by events from James’ biography, ranging from reprimands he received for speaking Welsh-accented English while in school to the moment he signed his contract to teach on the campus of the University of British Columbia.

____________________

1In the gallery’s press release, the show is billed as a collaboration between Storm Van Helsing and James.

2http://artforum.com/diary/id=8967

3http://www.ahva.ubc.ca/facultyIntroDisplay.cfm?InstrID=234&FacultyID=2

4http://www.miguelabreugallery.com/GarethJames.htm

5212-666-4466, 917-805-0882 and 212-864-0861, 2008.

6Althusser explained the consequences of interpellation: “in order to exist, every social formation must reproduce the conditions of its production at the same time as it produces, and in order to be able to produce.” Louis Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review, 1976), 128.

7These lacanian references were used by the artist in his statement about the exhibition, as well as during conversations with the author.

8Human Metal, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, October 22–December 23, 2011.

9Between 1907 and 1930, in a series of publications entitled The North American Indian, American anthropologist Edward Curtis documented the continent’s First Peoples, including those living on part of the territory occupied by the city of Vancouver. Claude Lévi-Strauss saw Curtis’s plates early in his career, and spent time in British Columbia on a study visit in 1973. The works from the series Untitled (2011) shown here include “obliterated” portraits of Lévi-Strauss from the time he was writing his memoir Tristes Tropiques, of General de Gaulle during his exile in England in 1942, and “The Cowichan Swathwé Mask,” a plate taken from The North American Indian, Vol. 9.

Inkjet print on canvas, nails

Courtesy of the artist, MontrealJon Knowles, Right Foot, 2013

Paint on orthopaedic body splint

Courtesy of the artist, MontrealAndrea Fraser, May I Help You?, 1991

Video, 20 min. 7 sec.

Performance presented as part of the exhibition May I Help You? In Cooperation with Allan McCollum, at the American Fine Arts Co. Gallery, New York City, 12 January – 2 February, 1991

Courtesy of the artist, Los AngelesThérèse Mastroiacovo, One and Half Seater, 1999 (from the body of work entitled politics of recognition, 1997-99)

Wood, metal

Courtesy of the artist, MontrealAndrea Fraser, Jeff Preiss, ORCHARD Document: May I Help You?, 1991/2005–06

16 mm, colour, digitized and transferred to Blu-Ray HD, 20 min.

Produced by ORCHARD and Epoch Films

Performance presented as part of the exhibition Part One (Luis Camnitzer, Moyra Davey, Andrea Fraser, Gareth James, Nicolàs Guagnini, Louise Lawler, Allan McCollum, John Miller, Christian Philipp Müller, Jeff Preiss, R.H. Quaytman, Martha Rosler, Daniela Rossell, Jason Simon, Lawrence Weiner), 11 – 29 May, 2005 (Fraser’s performances took place on 11, 15, 18 and 19 May)

Courtesy of the artists, Los Angeles and New York

Andrea Fraser, It’s a Beautiful House, Isn’t It? (May I Help You?), 1991/2011

Video, 17 min. 25 sec.

Camera and sound: Mark Escribano

Performance presented as part of the exhibition 91, 92, 93 (Andrea Fraser, Simon Leung and Lincoln Tobier), MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, 12 May – 31 July, 2011

Courtesy of the artist, Los Angeles“But if Kelly’s signature also functions not as the first or last articulation of a stable, self-possessed, constituting subject, but as a reduplication of the text of the process through which the subject is constituted, it is not simply a matter of bookcover semiotics.”Andrea Fraser, “On the Post-Partum Document,” Afterimage 13:8 (1986). Reprinted in Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; Vienna: Generali Foundation (1999) 214–18.Andrea Fraser was born in Billings, Montana, U.S.A. From 1984 to 1985, she attended the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum, New York. In 1991, she presented the performance May I Help You? at the American Fine Arts Co., “in cooperation with” Allan McCollum.1 McCollum was showing a selection from his series Surrogates, which consisted of plaster casts shaped like framed monochrome paintings. The introduction to the script for the performance reads, in part: “The objects—which have frames in shades of red, white ‘mats’, and black centers—are hung in a single continuous row, wrapping around three of the gallery’s walls. Seated behind a desk along the south wall of the exhibition space are three performers who constitute ‘The Staff.’ They are ‘busy’ with what looks like gallery work at a desk behind a three and a half foot white plaster-board wall. A visitor enters and marks her way to the center of the gallery. As she begins to look at the exhibition, one member of The Staff walks over and begins to address the visitor… ‘It’s a beautiful show isn’t it. And this … is a beautiful piece.’”2 In a text she wrote in 1992, Fraser quoted Colin de Land, director of the American Fine Arts Co.: “Whatever constitutes my appetite or sense of taste, I can be comfortable with a thing I select being next to something I find completely repugnant.”3 After de Land’s death and the closing of his gallery, Fraser co-founded the collaborative gallery Orchard, with a lifespan (2005–08) predetermined by its members.4 Andrea Fraser is a professor of New Genres in the Department of Art at the University of California, Los Angeles.5 She is represented by Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne.6In creating Post-Partum Document, Mary Kelly achieved a synchrony between Jacques Lacan’s theories of subjectivation and her day-to-day experience as a mother—and in so doing, displaced the authority of the former to turn them into a discourse among other discourses. Similarly, Andrea Fraser transposed Pierre Bourdieu’s reflexive method to her performative practice. In a tribute that she wrote to the sociologist, published simultaneously in the journals October and Texte Zur Kunst in summer 2002, she explained how reading Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979) shaped her early career: “Distinction exposed the paralyzing experience of illegitimacy with liberating clarity […]. But Distinction, as a product of Bourdieu’s relational, reflexive sociology, also made it impossible for me to imagine symbolic domination as a force that exists somewhere out there, in particular, substantive, institutions or individuals or cultural forms or practices, external to me as a social agent or as an artist—however young and disempowered I may have felt.”7 In the preface to an anthology of Fraser’s writings, Bourdieu himself acknowledged the epistemological value of her work: “Imagine a cleric, of no matter what creed, who discovered that ‘religion is the opium of the people’ and that ‘the agents of religion struggle for the exclusive right to control the benefits of salvation.’ Would such a cleric be able to continue priestly work? If so, how to?This is precisely the position in which Andrea Fraser has quite consciously and deliberately placed herself.”8 Some of the testimonials that Bourdieu used in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (1979, English translation 1984), to produce his analysis of inclusionary and exclusionary processes in culture were incorporated into the script for the performance May I Help You? (1991).9 The text, spoken by actors (and in later iterations, by Fraser), is divided into six sections, each comprising excerpts of conversations in which people talk about their emotional engagement with artworks and objects, some of which they own, and some of which they do not. Though they are stitched together by the continuum of the performance, these statements lose their anchorages in the voices of the subjects uttering them. The visitor might momentarily identify with the performer speaking in the name of an excluded viewer or, alternatively, feel nullified by that same subject, who at another moment represents an elitist “connoisseur”. Fraser explained this process of polyphonic oscillation: “With each voice, the speaker articulates her particular relationship to the almost identical artworks, affirming her own position while implicitly or explicitly negating the voices preceding and following her own.”10 The script for May I Help You? was updated on each occasion that Fraser re-performed the piece.11 The product of a collaboration with filmmaker Jeffrey Preiss, 2005’s Orchard Document (May I Help You?) evokes, among other things, the shifting of a community of chosen affinities (in which Fraser was a participant) from the American Fine Arts Co. Gallery to Orchard.12 For 91, 92, 93 (2011), Fraser reframed the performance as It’s a Beautiful House, Isn’t It? The MAK Center for Contemporary Arts and Architecture in Los Angeles invited three artists (Fraser, Simon Leung and Lincoln Tobier) to re-enact works from the early 1990s as a way of evaluating the critical paradigms of that period—paradigms which they themselves had helped shape. The May I Help You? script was adapted to the new site (the Rudolph Schindler–designed house that contains the MAK Center), interpolating allusions to real estate speculation. In 2013, for her retrospective at Museum Ludwig, Fraser came full circle, re-performing the piece with McCollum’s Surrogates.13

____________________

1Fraser wrote a text about McCollum that was eventually published in the catalogue for his show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, in June 1986. It was reprinted as “‘Creativity = Capital’?” in an anthology of Fraser’s writings, Museum Highlights: The Writings of Andrea Fraser, ed. Alexander Alberro (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 28–44.

2May I Help You? In Cooperation with Allan McCollum, American Fine Arts Co., 40 Wooster Street, New York, 12 January–2 February, 1991. Script for the performance. This is the initial version of the text; a subsequent iteration, “May I Help You?, 1991/2013,” appears in Fraser, Texte, Skripte, Transkripte / Texts, Scripts, Transcripts, ed. Carla Gugini (Cologne: Verlag Buchhandlung Walther König, 2013), 21–29.

3Andrea Fraser, “Another Kind of Pragmatism,” in Dealing With—Some Texts, Images and Thoughts Related to American Fine Arts Co., Valérie Knoll, Hannes Loichinger, Magnus Schäfer, eds. (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 34–38. First published in Forum International 11 (1992), 64–67.

4http://orchard47.org/testshow.php?name=Part%20One

5http://www.art.ucla.edu/faculty/fraser.html

6http://nagel-draxler.de/artists/andrea-fraser/

7Andrea Fraser, “‘To quote,’ say the kabyles, ‘is to bring back to life’,” in Museum Highlights, 80–87.

8Pierre Bourdieu, “Foreword: Revolution and Revelation,” in Museum Highlights, xiv–xv.

9These testimonials were gathered by Bourdieu and his team in 1974 and appeared as inserts throughout the book. Fraser cites this one, among others: “A Grand Bourgeois ‘Unique among His Kind.’ S., a lawyer aged 45, is the son of a lawyer and his family belongs to the Parisian grande bourgeoisie …” Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 289.

10Fraser, description of the performance, in “‘Creativity = Capital’?,” Museum Highlights, 34.

11Thus the performance has also been re-enacted during each of the distinct periods in Fraser’s career. In the mid-1990s, the artist began circumscribing her practice as a contractual offer of services, but abandoned that model early in the subsequent decade.

12http://artforum.com/diary/id=8967

13Besides these four iterations, Fraser also performed the piece in October 1991, in Galerie Christian Nagel’s booth at the Art Cologne.