Among All These Tundras

As a title, Among All These Tundras unites an expansive terrain reaching from Sápmi across Inuit Nunaat. It also invites us consider and find ourselves in the midst of a plurality of connections, concerns and standpoints shared between the twelve Indigenous artists participating in the exhibition. In their accompanying essay, the exhibition’s curators identify four themes uniting the works: language, land, sovereignty, and home.

As you visit the exhibition, keep these themes in mind and consider how each artist brings further nuance and variation to them.

Read moreLook for how language can be tied to processes of revitalization, how it can be a private vocabulary, and ask from where statements are made and to whom they are addressed.

Think about how land supports a standpoint, how narratives can follow a landscape, how a locale influences form, and how a territory can receive and register history and change.

Examine how sovereignty can be communicated through a gaze, read in retrospect, uncovered in archival material, or enacted in traditional practices or by going against the grain.

Reflect on how home might be found or felt in the familiar and ordinary, somewhere between the North and the South, how belonging can from a sense of stability or an apprehension of contradiction.

Composed and assembled thanks to contributions by Charissa Von Harringa and Amy Prouty, co-curators with Heather Igloliorte of Among All These Tundras.

Produced with the support of the Frederick and Mary Kay Lowy Art Education Fund

CloseCURATORS

Heather Igloliorte (Inuk, Nunatsiavut) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Art History at Concordia University in Montreal, where she holds a Research Chair in Indigenous Art History and Community Engagement. Heather has published extensively on Inuit and other Indigenous arts in academic journals such as PUBLIC, Art Link, TOPIA, Art Journal, and RACAR and in texts such as Negotiations in a Vacant Lot: Studying the Visual in Canada (2014), Manifestations: New Native Art Criticism (2011), and Curating Difficult Knowledge (2011). Heather also maintains an active curatorial practice. In 2016 she curated the permanent collection of Inuit art at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, Ilippunga, and launched the nationally touring exhibition SakKijajuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut; forthcoming projects include Alootook Ipellie: Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border (2018), and the inaugural exhibitions of the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Inuit Art Centre, opening 2020.

CloseAmy Prouty is a settler scholar and emerging curator of English, Irish, and Scottish descent and a doctoral student in the Art History program at Concordia University. Amy’s research focuses on the practice of urban Inuit artists and the role of art in community-building for Inuit diasporas. Her research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Amy holds a BA and an MA in Art History, both from Carleton University. Amy has curated an exhibition for the Carleton University Art Gallery entitled Keeping Record: The Documentary Impulse in Inuit Art and her writing has been featured in Inuit Art Quarterly.

CloseCharissa von Harringa is a doctoral student in Art History at Concordia University in Montreal. Her academic area of focus lies at the intersection of several fields including, Circumpolar, Indigenous, Postcolonial, and Performance Studies. Her personal and academic interests are directed towards the visual and material culture that emerge from transcultural histories, historiography, sociological theories, critical museology, Indigenous writings and performance practices, and the ever-evolving nexus of theory and practice in contemporary art. She holds a B.A. in Anthropology from New York University and a Master’s from Concordia University in Art History. She has co-curated several exhibitions, was a Curatorial Assistant for Inuit Blanche (2016), a historic large-scale Inuit arts festival (St. John’s, NL, 2016), and has authored several published essays. She comes from a very large family of fifteen children and has had an interesting set of life experiences and acquaintances that make up who she is today.

CloseARTISTS AND WORKS

Inukjuak, Nunavik and Montreal, Quebec

BIO

Asinnajaq is an Inuit artist, filmmaker, and writer from Inukjuak, Nunavik. Her most recent film, Three Thousand (2017), blends archival footage with animation to imagine her home community of Inukjuak from the past into the future. Three Thousand won Best Experimental film at the 2017 imagiNATIVE media arts festival, and was nominated for Best Short Documentary at the 2018 Canadian Screen Awards. She is a laureate of the REVEAL Indigenous Art Award in 2017 and the Toronto Film Critics Association’s Technicolour Clyde Gilmour Award in 2018. Recently, her work has been shown as a part of INSURGENCE/RESURGENCE at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. She is one of the curators of Tillitarniit, a three-day festival in Montreal which celebrates Inuit culture, and will be one of four curators working on the inaugural exhibition of the new Inuit Art Center in 2020.

WORKS

Rock Piece (Ahuriri edition), 2016

Video, colour, sound, 4 min. 2 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

Behind a seaweed-covered breakwater, a mound on a rocky beach heaves lightly. A stone falls giving way to another, soon revealing the artist’s body underneath. Slowly pushing herself up to her knees into a crouch and turns to the camera before lowering herself back down. As she does the stones follow—leaping, sliding and regrouping over her body.

Shot in Ahuriri, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Asinnajaq’s Rock Piece originates from an event score authored in 2015 and available to anyone to be performed:

Rock Piece

Feel the weight of the world;

free yourself

Such an action suggests a relationship between the body, environment and politics. Asinnajaq’s video cycles through two states of connection with the landscape, in one the body gives in to it, in the other it is exposed and cast against it. The stones too become animate, holding and releasing the body. Is feeling the weight of the world a feeling of freedom? That is, as an embodied connection to the land. Or, is to feel this weight an exercise to gauge its limits and breach it? Self-reflection followed by action.

EXPLORE

- The body and the land. Compare Asinnajaq’s and Laakuluk Williamson Bathory’s videos. How do they each present the body? What might be communicated in the gaze back at the camera?

- Envelopment and exposure. Asinnajaq’s score available to anyone to perform and “free yourself” and Kelliher-Combs’s repetition of a similar form in her drawings to hold her “secrets.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website: https://www.lichenolichen.com/

Georgeson-Usher, Camille. “Inuit Filmmaking That Sparks a Fire.” Canadian Art. January 23, 2018. https://canadianart.ca/features/studio-51-igloolik-imaginenative/

Igloliorte, Heather. “Tillutarniit: History, Land and Resilience in Inuit Film and Video.” Public 27, no. 54 (December 2016): 104-109.

Murphy, David and Isabella Weetaluktuk. “Episode 16.” Nipivut. Montreal, QC: CKUT 90.3 FM, May 3, 2016. http://www.isuma.tv/es/nipivut-our-voice-montreal-inuit-radio/episode-16-may-3-2016 (interview starts at 44:24).

CloseIqaluit, Nunavut and Maniitsoq, Greenland

BIO

Laakuluk Williamson Bathory is a Kalaallit performance artist and mask dancer in the uaajeerneq tradition, a storytelling performance that mixes humour, fear, and sexuality that she uses both as a cultural expression and a contemporary political statement. Although now based out of both Iqaluit and Maniitsoq in Greenland, she was born in Saskatoon where she trained and performed with her mother Maariu Olsen, a major figure in reviving the uaajeerneq artform during the 1970s. Bathory is one of the founding members of Qaggiavuut!, a community-based organization that supports the performing arts within Nunavut. Bathory is a frequent collaborator with renowned throatsinger Tanya Tagaq, performing with her in 2015 as a part of the #callresponse project that brought together Indigenous women across the continent as well as Tagaq’s Retribution (2016) music video.

WORKS

Timiga Nunalu Sikulu (My Body, the Land and the ice), 2016

Video by Jamie Griffiths, music by Chris Coleman, featuring vocals by Celina Kalluk

Video, colour, sound, 6 min. 28 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

In Timiga Ninalu Sikulu (My body, the land, and the ice) the camera follows an animal hide as it is dragged across the tundra, passing over tangles of tight, low-lying damp foliage, rough textured stone, and eventually out onto the ice. There another form comes into focus—a nude woman reclining on the hide, her back turned to the camera. As with the stones, the camera traces the curves of her body. Tunniit tattoos wrap around her arms and legs, one foot is inked black, a fur earring dangles. As it does the woman rises and turns to look back, meeting the viewer’s gaze with the painted and contorted face of an uaajeerneq dancer.

With her video, Laakuluk Williamson Bathory plays off of the trope of the reclining nude in Western art and the desire for women’s bodies and land within the colonial imagination. As a form of feminist self-portraiture, Bathory also offers a partial Indigenous view of the relations between land and body. Partial in the sense that when Bathory interrupts a lingering colonial gaze, she must also briefly turn away from her contemplation of the tundra, a vantage on the landscape that is solely her own.

EXPLORE

- Views of the land. Compare Bathory and Helander’s videos. How does the camera travel through the two landscapes? What is depicted?

- What qualifies a possessive gaze? A sexualizing gaze? A colonial gaze? What liberties does it assume when looking at land and bodies? And, by contrast, what does a self-possessed gaze deliver? What happens when you are caught looking?

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Adlington, Marilyn. “Navigating Reconciliation and Retribution in the Work of Laakkuluk Williamson-Bathory.” Representing Indigenous Peoples 2 (2017):1-9.

Broken Boxes Podcast. “Episode 46: Interview with Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory.” April 16, 2016. Audio, 1:02:05. http://www.brokenboxespodcast.com/podcast/2016/4/15/episode-46-interview-with-laakkuluk-williamson-bathory

Smith, Janet. “Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory taps into fear and humour for mask dance.” The Georgia Straight, March 14, 2018. https://www.straight.com/arts/1044321/laakkuluk-williamson-bathory-taps-fear-and-humour-mask-dance

CloseYellowknife, Northwest Territories and Edmonton, Alberta

BIO

Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter is a Yellowknife-born, Edmonton-based Inuvialuk artist and curator. A multi-disciplinary artist, they imbue a variety of mediums with their trademark ironic humour to address themes such as diaspora and mental illness. Nasogaluak Carpenter holds a BFA in Drawing from the Alberta College of Art and Design and recently completed the Indigenous Curatorial Research Practicum at Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Their installation Mourn (2017) was displayed at the Telus Convention Centre as part of The City of Calgary Arts and Culture Public Art Program and their piece Untitled (That’s A-Mori) (2016) was shown on digital billboards across Canada as a part of the Resilience National Billboard Project in 2018. Nasogaluak Carpenter is the first recipient of the Primary Colours Emerging Artist Award and, along with three Inuit curators, will be creating the inaugural exhibition of the new Inuit Art Centre in 2020.

WORKS

From the series Uyarak/Stone

Menstrual cup, 2017

7.62 x 5 cm

Cigarettes and Lighter, 2017

1 x 7.62 cm each and 2.54 x 7.62 cm

Tampax® tampon, 2017

10.16 x 2.54 cm

Soapstone and tung oil

Courtesy of the artist

In 1956, the Government of Canada introduced the Igloo tag as a means of authenticating Inuit sculptures and other works before they went to market. Informed by techniques in sculpting and drawing long practiced by Inuit, the production of sculptures for sale commenced with contact and developed into a modern industry in the mid-twentieth century. As artworks made for a market and highly visible in the South, Inuit sculptures under settler eyes are at times taken as easy summaries of Inuit culture or confused as artefacts. Consequently, the contemporaneity of Inuit art—its complex history between commercial and traditional practices as well as modern artistic innovations—is overlooked.

Carving cigarettes and a lighter, a tampon, and a diva cup out of soapstone, Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter responds to the limits on what counts as authentic, marketable or recognizable Inuit art. Working in soapstone Carpenter exploits its capacity to code things as “Inuit,” claiming a place within Inuit art production for the representation of the everyday and valorizing these commodities as components of Inuit contemporary life. Carved to a one-to-one ratio and displayed under Plexiglas, each sculpture could potentially leave the gallery to commingle with the products they mirror.

EXPLORE

- Think about the sculptures and the products they represent in relation to the body.

- Utility and representation. Consider how both Carpenter and Van Heuvelen work with sculpture in approximation yet sacrifice functionality, in order to highlight forms, tools and products in the North.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website https://cargocollective.com/nasogaluakcarpenter

Carpenter, Jade Nasogaluak. “Thinking Beyond the White Frontier.” Canadian Art. Reviews. October 16, 2017. https://canadianart.ca/reviews/thinking-beyond-white-frontier/

Gallpen, Britt. “Profile: Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter.” Inuit Art Quarterly. 30, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 20.

Vee, Mel and Jacquie Gallos Aquines. “Episode 2: Conversation with Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter.” The Unlearning Channel. November 28, 2017. https://cjsw.com/program/the-unlearning-channel/episode/20171128/

CloseMalmö, Sweden and Kittelfjäll, Sápmi

BIO

Carola Grahn is a Sámi visual artist based out Malmö, Sweden and Kittelfjäll in Sápmi. Grahn works primarily with materializations of text, installation strategies and sculptural media. Her affective text- and sound-based sculptural installations lend poetic dialogue to the contexts of place, labour, and identity that are attuned to the slippages of language and representation in art while complicating cultural and gendered social constructions of the North. Carola is an internationally-known artist in northern Scandinavia and abroad, whose work has been shown at Southbank Centre, 2017 (London, UK), Carleton University Art Gallery, 2017 (Ottawa), Art Gallery of Southwestern Manitoba, 2017 (Brandon), Office of Contemporary Art Norway, 2017, Tråante, 2017 (Nor), Havremagasinet, 2016 (Sweden), Art Centre KulttuuriKauppila, 2016 (Fin), Bildmuseet, Umeå (Swe), 2014, Galleri Jinsuni, Seoul, 2014 (South Korea) amongst other places. Grahn has been the guest editor of Hjärnstorm magazine 2017, she has written for Afterall (2017) and published the conceptual novel Lo & Professorn (2013). Grahn’s work is also represented in the Swedish Art Council’s collection.

WORKS

Look Who’s Talking, 2016

Video, 3 min. 40 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

Look Who’s Talking an animated trio of Sámi ceremonial drum skins spin against a starry night sky, popping up between three other text-based animations. My God, recounts the artist’s attempts to tease out the location of a ceremonial offering site from her father and uncle, each offering her only vague directions amidst brotherly antagonisms and a shared sense of knowing despite maybe not knowing. In WTF, Grahn tells of her elation during a conversation among fellow Indigenous artists about the absurdities and nuisances of a White-dominated art world, followed by a private reflection on passing as White. No Need returns to a dream where Grahn is overcome by a sense of liberation in a world without the need for art and the letdown upon waking to her usual studio routine.

There’s little resolution to Grahn’s wry, over-caffeinated stories as they barrel through the contradictions of family relations, pop culture, the art world, and day-to-day anxieties in the studio. It is, however, in these confusions that Grahn finds the processes towards forming one’s self image. The spinning drums, as an identifiable Sámi element, can be seen as a sort of station identification or inter-title between episodes, accenting an at times dizzying and ever-changing standpoint.

EXPLORE

- Everyday identity. Consider how Grahn speaks from and reflects on a Sámi standpoint and identity. Is it centred in her accounts? Or is it matter of fact? Does it cause contradictions? Or open up onto further stories?

- Compare Grahn’s approach to story telling with Helander’s? Can you imagine transcribing Helander’s story into text? And vice versa, can you see Grahn’s acted out? What might be lost or gained?

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website http://www.carolagrahn.se/

Art Centre KulttuuriKauppila. “My Name is Nature: Carola Grahn.” Video, 3:17. Posted August 16, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VgVfbZi4qg

Grahn, Carola. “The Delicate Difference Between ‘Thinking at the Edge of the World’ and Thinking About the Edge of the World.” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context, and Enquiry, no. 44 (Autumn/Winter 2017): 32-43

CloseUtsjok and Helsinki, Finland

BIO

Marja Helander is a video artist and photographer based in Utsjok and Helsinki, Finland. Her multi-media practice draws from her Sámi and Finnish ancestry. Helander explores themes related to femininity, identity and the tension between traditional Sámi ways of life and modern Finnish society. Her recent work concentrates on post-colonial topics among Sámi including industry and resource extraction in the North with photography and video art that feature the Northern landscape and Sami issues of modernity through a tragicomic lens. Although originally trained as a painter, Helander decided to pursue her interest in photography, graduating from the University of Art and Design in Helsinki in 1999. Since then she has presented works in solo and group exhibitions both in Finland and abroad, with many shows in northern Scandinavia, Canada, South Africa, and Mali. Her video work Dolastallat won the Kent Monkman award at imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival in Toronto, 2016. In 2017, Helander was chosen as the Finnish Cultural Institute in New York’s artist-in-residency. Her recent short, Birds in the Earth won Risto Jarva Prize and the Main Prize in the National Competition in the Tampere Film Festival 2018 in Finland. Helander´s works are also included in collections in several Scandinavian museums and in the National Gallery of Canada. Helander has also made a public artwork So Everything Flourishes for the Sámi Cultural Centre Sajos, in Inari.

WORKS

Dolastallat (To have a campfire), 2016

Video, colour, sound, 5 min. 48 sec.

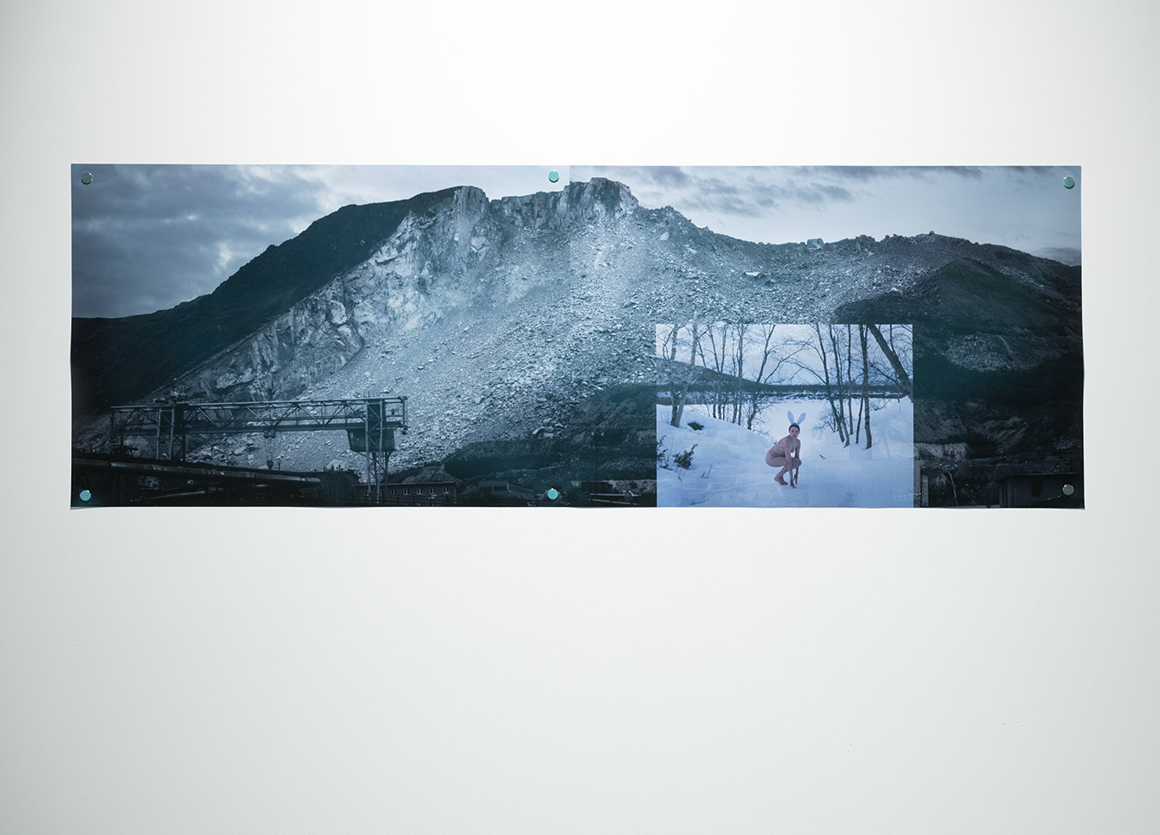

Night is Falling, 2018

Somewhere Far Away, 2018

Digital inkjet prints on archival paper

62 x 183 cm

62 x 174 cm

Courtesy of the artist

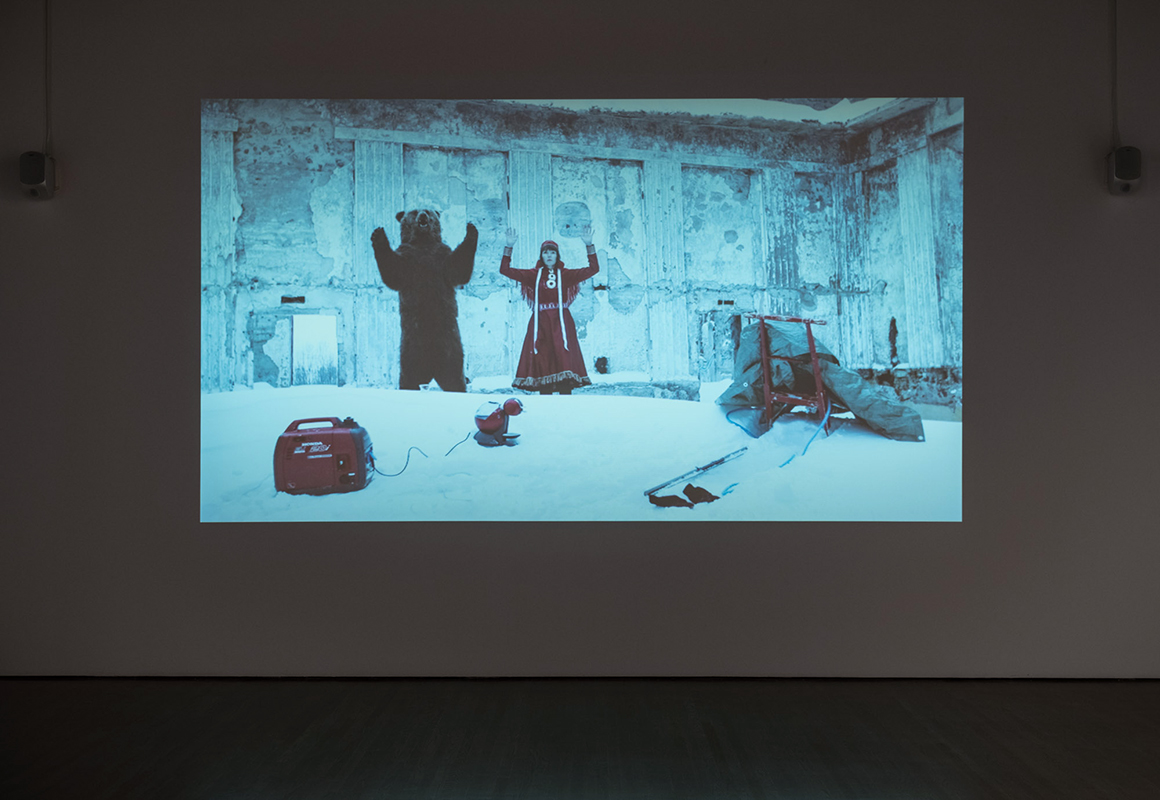

Dolastallat opens with a view of a woman pushing a sled through Kola Peninsula in Russia, the eastern most region of Sapmi. Dwarfed by massive industrial infrastructure and a long mountain range on the horizon, she arrives at an abandoned building and enters to find a taxidermied bear standing in the snow. From her sled she unpacks a small tea percolator and portable generator, brews a cup of tea with a handful of snow and offers it to the bear. After no reaction, she moves to mimic its pose before packing up again and returning to her journey.

In five short minutes, Helander engages with Sámi mythology, questions of ecology, and the impact of the northern extraction industry. Moving between active industrial sites and ruins, Helander measures out the scale and impact of these operations. With her consumer appliances matching the red of her traditional clothing, or vice versa, she sets a contemporary campfire and retells a Sámi myth on hospitality in the midst of intrusions and changes within traditional territory and culture. The neighboring photographs Night is Falling and Somewhere Far Away, offer starker comparisons of a landscape seen through the lens of mythology or scared by extractive industry.

EXPLORE

- Visual cues. With Carpenter’s, Nango’s and Van Heuvelen’s works in mind, consider how Helander plays with a sense of contemporaneity through her choice of props.

- Land and extraction. Think about how Helander adjusts and adds to Sámi mythology in order to account for current issues.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website: http://www.marjahelander.com/

Helander, Elina and Kaarina Kailo, eds. No Beginning, No End: The Sámi Speak Up. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1998. [Photographs by Marja Helander]

Jørgensen, Ulla Angkjær. “Performing the Forgotten: Body, Territory, and Authenticity in Contemporary Sámi Art.” In Sámi Art and Aesthetics: Contemporary Perspectives. edited by Svein Aamold, Ulla Angkjær Jørgensen, and Elin Haugdal, 249-266. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2017.

CloseNome, Alaska

BIO

Sonya Kelliher-Combs is an Iñupiaq and Athabascan artist from the Alaskan community of Nome. Through her mixed media painting and sculpture, Kelliher-Combs offers a chronicle of the ongoing struggle for self-definition and identity in the Alaskan context. Her combination of shared iconography with intensely personal imagery demonstrates the generative power that each vocabulary has over the other. Similarly, her use of synthetic, organic, traditional and modern materials dissolves binaries of Western/Native culture, self/other and man/nature, to examine their interrelationships and interdependence while also questioning accepted notions of beauty. Kelliher-Combs’s work has been shown in numerous individual and group exhibitions, including the national exhibition Changing Hands 2: Art without Reservation and the inaugural Sakahàn quinquennial of Indigenous art at the National Gallery of Canada in 2013. Recent exhibitions include Hide: Skin as Material and Metaphor at the National Museum of American Indian Art in 2010 and the traveling exhibition THIS IS DISPLACEMENT: Native Artists Consider the Relationship Between Land and Identity in 2011.

WORKS

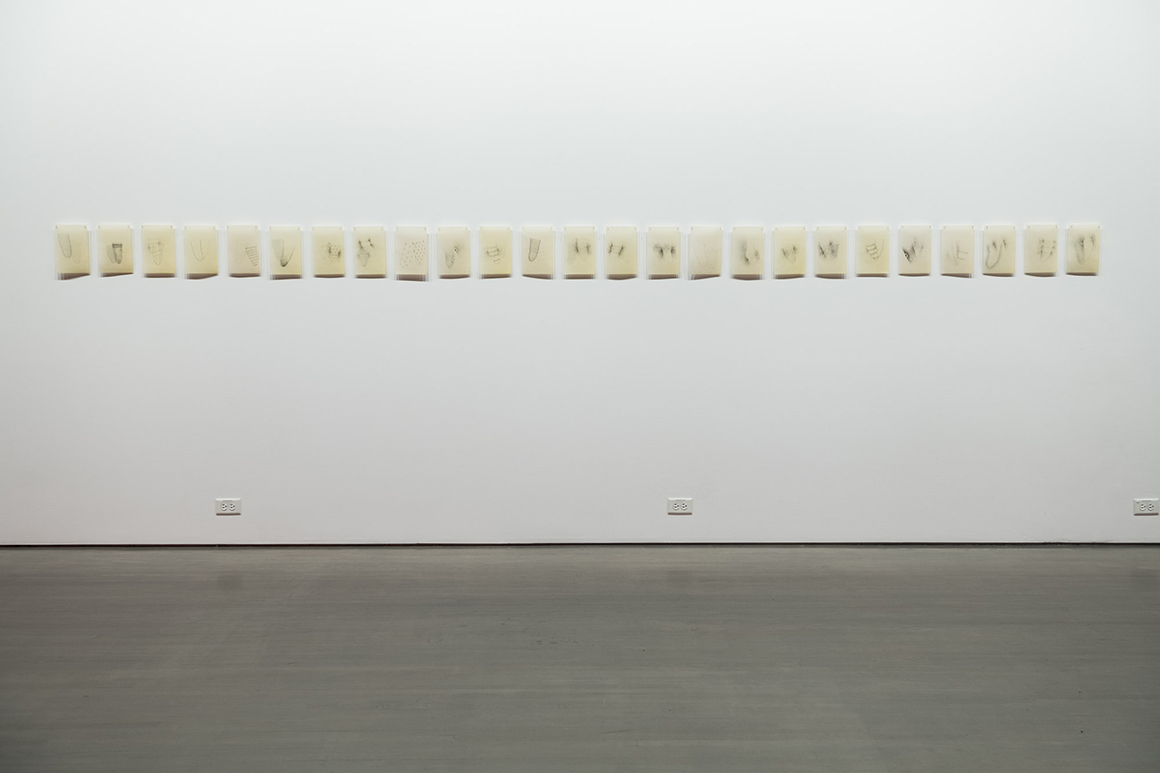

Secret Portraits, 2018

Ink, pencil, beeswax on paper

22.86 x 15.24 cm

Courtesy of the artist

An oblong and unfinished ellipse is the principle form of Sonya Kelliher-Combs’s on-going Secrets series. Curve pointed downwards and with a gap at the top, the form is clearly left open-ended. It is filled with tight patterns, suggesting knitwear and ornamentation. It sprouts short lines as if grown hairy or bears small leaves as if a small plant. A fleshy feeling of envelopment is lent tactility thanks to the beeswax-coated paper, through which another drawing can be seen on the backside.

As “secrets,” these are vessels for Kelliher-Combs’s personal vocabulary.

This system draws from traditional textile patterns, receives ink like a tattoo, wears something like animal hide, and moves with an erotic charge. The membranous paper offers the illusion of three-dimensionality by exposing a back view of the drawing on the opposite side, this doubling stirring an animated correspondence between the two forms as they overlap. Transmitting both sides of its surface, the paper also acts as a dividing screen between the drawings. With Secrets, Kelliher-Combs works with properties of transparency, opacity, symbolism and abstraction across an ever-evolving system, this variation ensuring any legibility rarely settles in the open for long.

EXPLORE

- The unsaid. Kelliher-Combs’s considers her drawings as containers, storing accounts, experiences, and knowledge. Examine the different ways that information is retained, disclosed or withheld throughout the works in the exhibition.

- Personal forms. Think about how Kelliher-Combs’s adapts and gestures toward traditional patterns and materials, combining them in a form that is uniquely her own. Compare this strategy to Grahn’s storytelling or Partridge’s panels.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website http://www.sonyakellihercombs.com/index.html

Ash-Milby, Kathleen. “Sonya Kelliher-Combs: Secret Skin.” In Hide: Skin as Material and Metaphor, edited by Kathleen Ash-Milby, 41-51. Washington: National Museum of the American Indian Editions, 2009.

Hutchinson, Elizabeth. “What Lies Beneath.” Art in America 105, no. 9 (October 2017): 72-75.

Nordamerika Native Museum. “Sonya Kelliher-Combs.” Video, 2:56. Posted January 21, 2015. https://vimeo.com/117427068

CloseAlta and Tromsø, Norway

BIO

Joar Nango is a Sámi and Norwegian architect and visual artist, born in Alta, Norway, and who currently lives and works in Tromsø, Norway. His varied practices often involve site-specific performances and structural installations which explore the intersection of architecture and visual art, drawing from both his Sámi heritage and Western culture. Nango is a co-founder of the architecture collective FFB, who create temporary installations in urban settings. He has exhibited in Canada at Western Front (Vancouver, 2014) and Gallery 44 (Toronto, 2016) and internationally at 43SNA, Medellin (Colombia, 2013), and the Norwegian Sculpture Biennale at Vigelandsmuseet (Oslo, Norway, 2013). One of his recent projects was European Everything (2017) at Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel, an extensive installation and performance which involved collaborations with Sámi and European artists, writers, poets and musicians.

WORKS

Sámi Shelters #1 – 5, 2009 –

Hand-knitted woollen sweaters in ten different shades of colour

Variable dimensions

Courtesy of the artist

Pack a sweater. Another way of saying: be ready for change. You keep a sweater folded up in your backpack, suitcase or in a drawer for when the temperature drops, an extra layer to keep moving, to settle in for the night, or to keep the heating bill down. Pack a sweater. Keep an eye on the weather. Stay sensitive to your surroundings and be prepared to adapt to the environment. Trained as an architect, with Sámi Shelters Nango literally knits images of nomadic Sámi architecture into traditional Norwegian sweater patterns. Taken together, the five sweaters add up to a short, wearable typology of the lavvu form, a nomadic tent used by Sámi reindeer herders, and its incorporation into permanent structures throughout the Sapmi region. In a sly reference to critical regionalism, which lauds a sensitivity to place over flattening design and accounts for the body’s experience of space beyond the visual, Nango offers with his sweaters a tactile and graphic way of analyzing the consequences within both Sámi and Norwegian contexts of reducing traditional architecture to a fixed and outwardly symbolic role.

EXPLORE

- Other forms of publishing and learning. How Nango’s sweaters are a mobile and wearable resource, each reproducible through a knitting pattern.

- Hybridity and entwinement. Considering how Nango uses classic Norwegian sweater patterns, another popular icon of Nordic culture, as a vehicle for his architectural study.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Bydler, Charlotte. “Decolonial or Creolized Commons?: Sámi Duodji in the Expanded Field.” In Sámi Art and Aesthetics: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Svein Aamold, Elin Haugdal, and Ulla Angkjær Jørgensen, 141- 162. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2017.

Hopkins, Candice. “Joar Nango: Temporary Structures and Architecture on the Move.” Mousse 58 (April-May, 2017).

Lundström, Jan-Erik. “Quotidian Transcendence, Ephemerality and the Inertia of the Nation-State: Notes on the Work of Joar Nango.” In The Ruined Archive, edited by Iain Chambers, Giulia Grechi, and Mark Nash, 297-305. Milano: Politecnico di Milano, 2014.

CloseKuujjuaq, Nunavik and Kautokeino, Norway

BIO

Taqralik Partridge is an Inuk artist, writer, curator, throatsinger, and spoken word poet. She is originally from Kuujjuaq in Nunavik, although she now splits her time between Canada and Kautokeino in northern Sápmi. Partridge’s writing focuses on both life in the north and on the experiences of Inuit living in the south, featuring a mix of influences from hip-hop to Inuit storytelling. Partridge co-founded the Tusarniq festival held in Montreal. Her performance work has been featured on CBC radio one and the BBC program and she has toured with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. Partridge has also worked as Director of Communications for the Avataq Cultural Institute. In 2010, her short story Igloolik won first prize in the Quebec Writing Competition and the same year she was a featured artist onstage at the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver. In 2018, Partridge was named as a finalist for the CBC Short Story Prize.

WORKS

Tusarsauvungaa, 2018

Cotton, polyester, wool, silk, glass beads, metal beads, Canadian sealskin, reindeer leather, reindeer antler, thermal emergency blanket, Pixee lures, plastic packaging, Canadian coins, arctic willow branches, dental floss and artificial sinew

Variable dimensions

Courtesy of the artist

Tusarsauvungaa is the transliteration of ᑐᓴᕐᓴᐅᕗᖔ, which can be read on one of Taqralik Partridge’s beaded works and translates as “Can you hear me?” Each panel is a variation of those affixed to the front of an amauti—women’s traditional parka. Amautiit are outerware specifically designed for the care of infants, who are carried underneath the hood close to their mother’s back. Such body-to-body contact opens up an array of communication. Worn outward the panel’s question—Can you hear me?—is also issued from the standpoint of Inuit women, centering their experience and voice.

Traditional in form, Partridge uses a mix of natural and readymade materials for her panels. Note the quarters and loonies dangling from beaded threads at the base of each. Pulled from circulation, the coins might represent an afront to the Canadian state, or gesture to the use of found material in amauti design. Yet, as ornaments they are also close to the land, made up of nickle and copper, two metals heavily mined in Canada. Opposite the Queen on the quarter is a caribou, an essential animal for Inuit providing hide, fur and sinew for cloathing, bones and antlers for tools and meat for food.

EXPLORE

- Address and standpoint. What are the different ways that “Can you hear me?” can be asked? And, conversly, what are the different ways that it can be heard?

- And what of the panels’ place in the gallery? Think about questions of use and display as shared between Partridge, Carpenter, Van Heuvelen, and Warden’s respective works.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Duvicq, Nelly. “Le territoire dans le corps. Figurations du Nord et de son absence dans la poésie orale et écrite de Taqralik Partridge.” Temps Zéro 7, no. 7 (2013). http://tempszero.contemporain.info/document1082

Partridge, Taqralik. “Throatsinging: More Than a Game.” Inuit Art Quarterly 16, no. 4 (Winter 2001): 6-10.

Partridge, Taqralik and Keavy Martin. “‘What Inuit Will Think’: Keavy Martin and Taqralik Partridge Talk Inuit Literature.” In The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature, edited by Cynthia Sugars, 191-208. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

CloseRigolet, Nunatsiavut and Ottawa, Ontario

BIO

Barry Pottle is an Inuk artist from Nunatsiavut in Labrador (Rigolet), now living in Ottawa, Ontario. He has worked with the Indigenous arts community for many years particularly in the city of Ottawa. Barry has always been interested in photography as a medium of artistic expression and as a way of exploring the world around him. Living in Ottawa, which has the largest urban population of Inuit outside the North, Barry has been able to stay connected to the greater Inuit community. Through the camera’s len, Barry showcases the uniqueness of this community. Whether it is at a cultural gathering, family outings or the solitude of nature that photography allows, he captures the essence of Inuit life in Ottawa. From a regional perspective, living in the Nation’s Capital allows him to travel throughout the valley and beyond to explore and photograph people, places and events, as well as articulate and interrogate the emergent identity of an “urban Inuk.” His projects have included the “Foodland Security”series which highlights the importance of access to country food in urban communities and the “Awareness” series which documents the history of the Eskimo ID tags and the elders who wore them. Mostly self-taught, his work is rooted in photojournalism. His work can be seen in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Museum of History, and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

WORKS

The Last Supper, 2014

Digital inkjet print on archival paper

50 x 75 cm

From the series Foodland Security

After the Cut, 2012

Community Freezer, 2012

Kanon-ized, 2012

Digital inkjet prints on archival paper

50 x 75 cm

75 x 50 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Barry Pottle’s photographs emerge from his observation of and personal experience with access to traditional or “country” food among urban Inuit. In Community Freezer, the distribution of frozen fish speaks to food sharing, collective freezers stocked by hunters and fishers in northern communities, and the extension of this practice to the South. After the Cut shows frozen caribou meat and a pair of uluit, all-purpose knives reserved for and used by women for preparation and serving. Kanonized frames tin cans, useful for their long shelf life, and an ulu bearing an Igloo tag. The sticker, issued to commercial galleries to authenticate Inuit art, is Pottle’s wink to the program’s limits on what counts as Inuit art. The Last Supper with its partially butchered caribou head in a bowl might read as an Inuit variation on Dutch still-life or Renaissance paintings, or as a retort to Christianity and conversion. Keeping food sovereignty in mind, the emphasis on last can also be heard as “the last time we prepared and ate caribou meat together.” Not a final meal but simply the last time there was supper around country food; last time in anticipation of the next time.

EXPLORE

- Community and process. How does Pottle photograph a practice and a means of living? What does his framing show? What does it exclude? What do the more arranged photos communicate?

- Close view on the everyday. Compare Pottle’s study of one important element of urban Inuit life with Storch’s use of found footage of Kalaallit life in Greenland.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website http://barrypottle.com/

Inuit Art Foundation. “The Silatani Series: An Artistic Exploration of the Experiences of Urban Inuit.” Inuit Art Quarterly 28, no. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 2015): 30-35.

Pottle, Barry. “Access to Inuit Country Food in an Urban Setting – As Told by Barry Pottle Through Contemporary Inuit Art Photography.” Journal of Aboriginal Health 9, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 50-62.

Thibault, Martin. De la banquise au congélateur : mondialisation et culture au Nunavik. Québec : Presses de l’Université Laval, 2003.

CloseSisimiut, Greenland and Copenhagen, Denmark

BIO

Inuuteq Storch is a Kalaallit visual artist, photographer, musician and author based in Copenhagen, Denmark and Sisimiut, Greenland. Storch received his photography certifications from the International Center of Photography in New York in 2016, and at Fatamorgana in Copenhagen in 2011. The artist’s practice in photography, film, video, music and installation, incorporates archival and contemporary images to comment on colonialism and the present day impacts and realities of modernization on Greenlandic communities. He is the author of Porcelain Souls (2018), a collection of family photos and letters from Greenland in the 1960s, and anticipates a forthcoming publication this December. Storch has participated in several festivals and major international solo and group exhibitions including: Old Films of the New Tale (Sisimiut Culture House, Greenland, 2017) and Run Away For Mother Earth (Katuaq, Nuuk Culture house, 2012). His group shows include Chirts & Cloves (Nuuk Kunst Museum and Sisimiut Culture House, 2018), Notas Al Futuro (Espacio El Pasajero, Bogota, Colombia, 2017), and the Pop Up Archive Exhibition, MANA (New Jersey, 2017).

WORKS

Old Films of the New Tale, 2016

2-channel video, colour, sound

16 min. 10 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

Inuuteq Storch’s two-channel video Old Films of the New Tale reworks archival footage of life in Greenland. Of value for Storch is the depiction of everyday life and the comingling of the traditional and the modern. Mirroring effects lend a panoramic extension to the landscapes, while further manipulation brings a prism-like distribution to the events and experiences recorded, building out of the limited footage a multiplicity of views and an elastic sense of time. This “new tale” seen in these “old films” may speak to the conjunction of traditional and contemporary life, yet key is that it is a new tale among older tales under the care of the Kalaallit.

In the series At Home Where We Belong Storch documents contemporary life in Greenland. The photos show subjects in a range of urban and rural spaces: besuited in a rocky meadow, seated on a collapsed couch on a snowy road facing a microwave on chair, dressed in traditional clothing at the side of a road. Under question is the formation of identity when negotiating imported culture and traditional ways of life, the series offering a realist look at life in Greenland and inviting close scrutiny of what counts as familiar.

EXPLORE

- What techniques in editing does Storch use to tell his “new tale”? How might this differ from simply presenting the films as is, as documents or artefacts?

- Conflicted and uncompromising. Think about how Storch documents contemporary Kalaallit life and its surroundings in his photographs. Staged or otherwise in what ways are local and imported elements legible? What is not legible to you as Kalaallit or otherwise? Where are the distinctions blurred?

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website https://www.inuuteqstorch.com/

Enge, Marianne. “If we’re all Nordic, are some of us more Nordic than others?” Kunstkritikk. November 28th, 2017. http://www.kunstkritikk.no/artikler/if-were-all-nordic-are-some-of-us-more-nordic-than-others/

CloseIqaluit, Nunavut and Toronto, Ontario

BIO

Couzyn van Heuvelen is an Inuit artist born in Iqaluit but who has lived most of his life in Southern Ontario. His artistic practice blends modern fabrication techniques with Inuit tradition to create “hybrid” objects that explore both cultural tensions and synchronicities. Van Heuvelen holds a BFA from York University and an MFA from NSCAD University. His work has been included in several group exhibitions across Canada. Recently, van Heuvelen created an aluminum qamutiik sculpture at the Southway Inn in Ottawa, Ontario for the Lost Stories Project commemorating the historical significance of the hotel being a landing point for Inuit traveling south for school, employment and medical care. In 2017, van Heuvelen was chosen as the Sheridan College Temporary Contemporary Artist in Residence and the subsequent work, Nitsiit (2017) was featured at Sheridan’s Hazel McCallion Campus in Mississauga.

WORKS

Qamutiik, 2014

Industrial found wooden pallets

12 x 243 x 91 cm

Courtesy of the artist

As a hybrid object, van Heuvelen’s Qamutiik carries an air of ambivalence and skepticism. Following traditional design, a qamutiik is a sled used by Inuit for multiple purposes and are highly efficant vehicles for travel across varied icy and snowy terrain. Here van Heuvelen pairs two wooden pallets, stripping some of the top planks from the end of one and bending the exposed supporting planks upwards to the effect of mirroring the sled’s basic form. Pallets are ubiquitous in now sedentary northern communities that depend increasingly on shipments of food and goods. With Qamutiik two forms of transportation representing two ways of living, in movement and fixed, are compounded into one.

Neither here, nor there, Qamutiik is caught in a state of change. The distorted pallets promise no arrival at a functional equivalent to the sled. Yet, while movement is stalled, the work still points to potential manoeuvres. These are middling moves, strategies for navigating the intersection of two forms and ways of life not knowing where the encounter will end up. Without looking for an end point, nor contrasting one form as old and the other as new, Qamutiik lingers in this moment of transition.

EXPLORE

- Bad hybridity. What is at stake in investigating incongruity rather than ingenuity?

- Global and the local. Pallets for van Heuvelen represent the debris of a global market in the North. Compare the modified pallets in the gallery to what can be seen in Storch’s documentation of back-lots and roadsides in Greenland.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website http://www.couzyn.ca/

Art Gallery of Mississauga. “Couzyn Van Heuvelen: Nitsiit.” Video, 11:23. Posted March 9, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqJa4XIpejA

Gallpen, Britt. “Profile: Couzyn Van Heuvelen.” Inuit Art Quarterly 29, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 16-17.

CloseKaktovik and Fairbanks, Alaska

BIO

Allison Warden is an Iñupiaq interdisciplinary visual and performance artist who raps under the name AKU-MATU. She was born in Fairbanks, Alaska with close ties to Kaktovik, Alaska and is now based in Anchorage. Warden’s practice weaves together Iñupiaq narratives and traditions from the past, present, and imagined futures. She is the creator of one-woman show, “Calling All Polar Bears” which in 2011 was part of a National Performance Network residency. Her most recent work is Unipkaaġusiksuġuvik (the place of the future/ancient) at the Anchorage Museum in Alaska in 2016, featured an extensive performative installation piece in which she was present in the gallery for 390 hours over two months. As AKU-MATU, she performed at the Riddu Riddu Music Festival in 2018 as part of the Inuit Circumpolar Hip-Hop Collaboration. In 2018, Warden was awarded the Rasmuson Individual Artist Fellowship in the new genre category.

WORKS

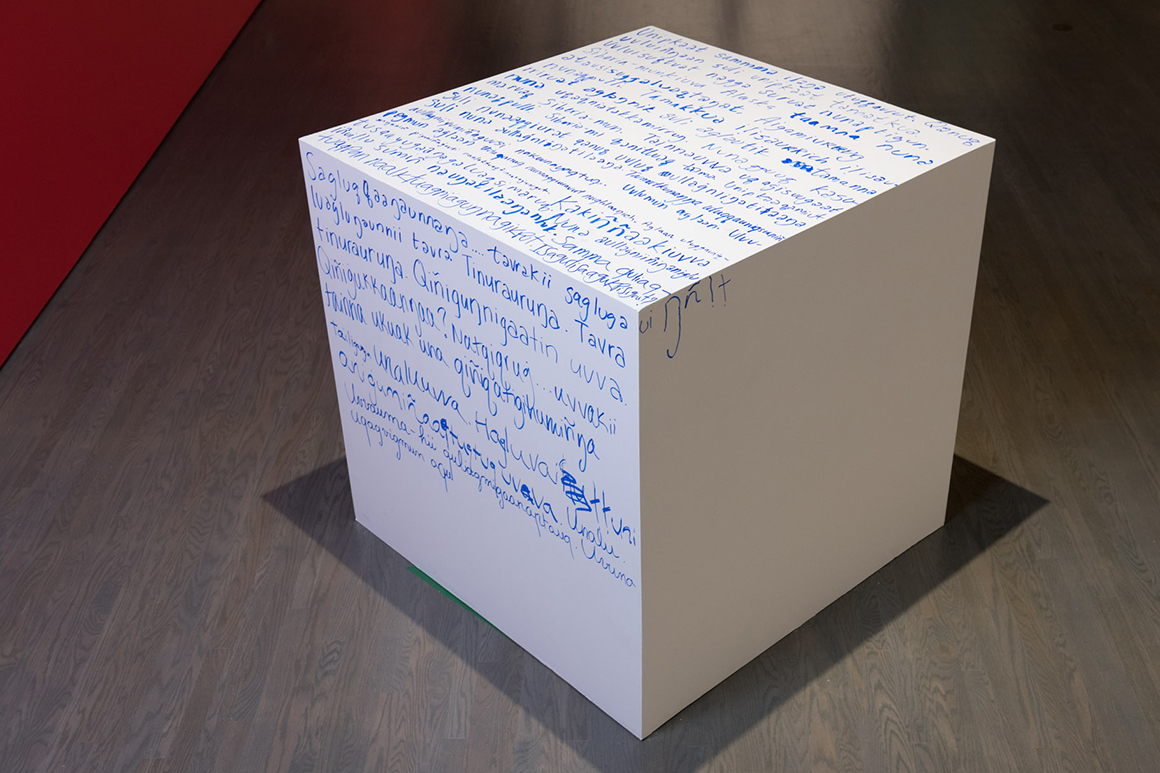

siku/siku, 2017

Two-part performance with a plinth

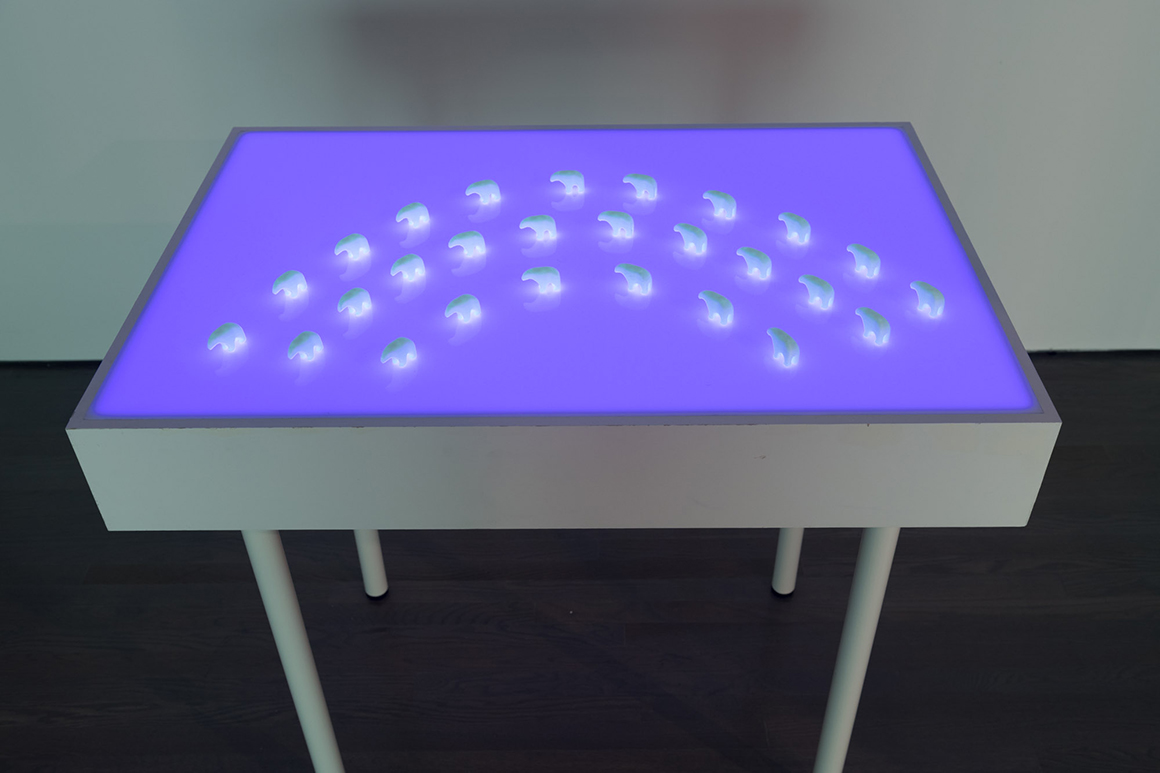

we glow the way who choose to glow, 2018

3D printed figurines in glow-in-the-dark filament

2.5 x 4 cm x 1.5 cm

Courtesy of the artist

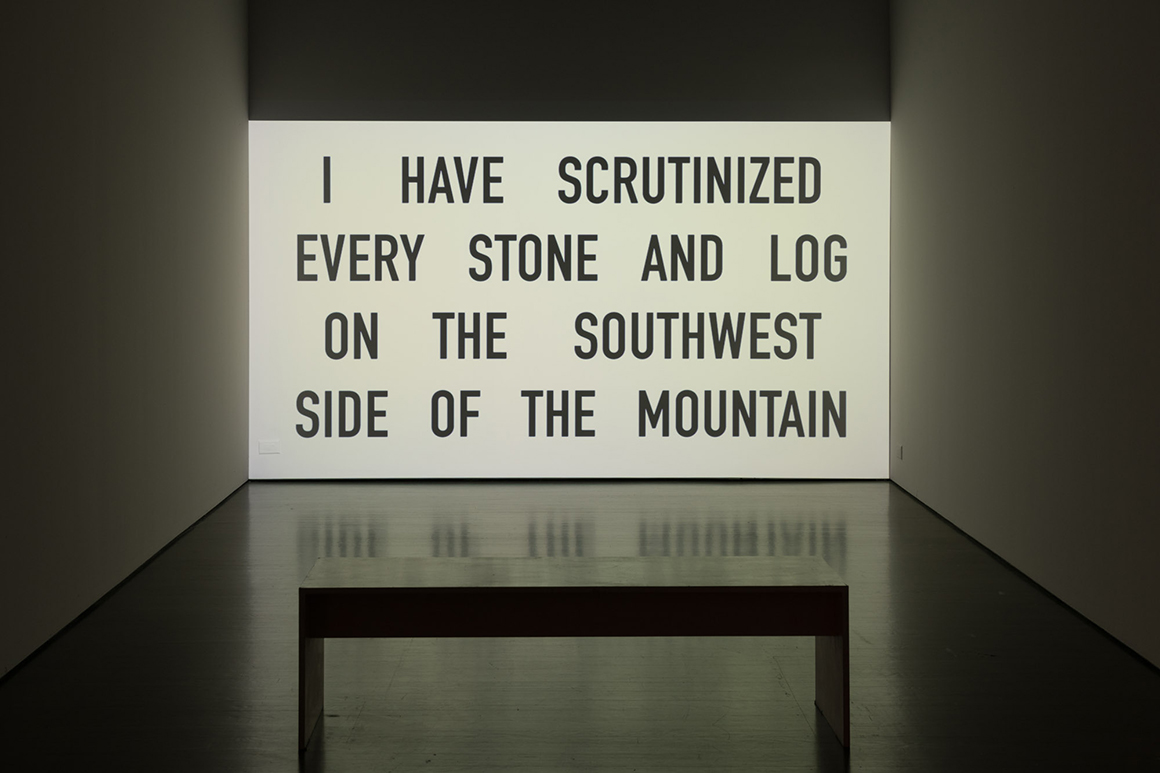

In the gallery’s principle space is a large, white cube covered with handwritten Iñupiaq words and phrases. It sits as a trace of siku/siku, a two-part performance by Warden. Siku is ice in Iñupiaq, it is also slang for methamphetamine in Arctic communities. Over two performances Warden personifies both readings of the word. Starting with the latter, Warden sits atop the cube during the exhibition’s opening and recites a fragmented monologue entwining personal history, private narratives, mythology, singing, asides to passers by, testimony of intergenerational trauma, and pronouncements on the perseverance of Iñupiaq life. All delivered in a performance coded as itinerant, intoxicated, and disconnected. The following day she mounts the cube again, this time with an Iñupiaq dictionary and works through exercises while writing on the cube.

Assuming different positions, each character exhibits a consciousness of the struggles toward Iñupiaq resurgence in face of racism and colonisation. Sharing the cube, Warden’s protagonists antagonize their state of display. The first solicits glances awry, adding pressure to the routine exhibition opening. The second’s use of Iñupiaq language promises legibility to few visitors, yet leaves behind a record and a potential reference tool.

We glow the way we choose to glow assembles a group of identical 3D printed polar bears, copied from an ivory sculpture by Warden’s great uncle, Stephen Patkotak. Working with this keepsake, Warden again introduces questions on transmission, inheritance, and continuity, as well as on the measures of authenticity with regards to craftwork and the display of Indigenous culture.

EXPLORE

- Presence and absence. Consider Warden’s and Partridge’s respective use of language. How do these texts speak for an absent speaker? To whom might they address?

- Reproduction and reinterpretation. Think about how many of the artists in this exhibition reformulate stories, histories and forms familiar to them. How are they modified, retold or presented? What can be seen, heard or felt through these alternate angles?

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Artist’s website https://www.allisonwarden.com/

Deedy, Alexander. “Inupiaq Art: Allison Warden shares her perspective.” Alaska. 83, no. 8 (October 2017): 21.

Holthouse, Hensley and Priscilla Naunġaġiaq. “Finding Magic: The Future/Ancient of Allison Akootchook Warden.” Inuit Art Quarterly 30, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 32-39.

Warden, Allison Akootchook. “A Way to Inspire Conversations within Community.” Filmed April 16, 2011 at TEDxAnchorage, Anchorage, Alaska. Video, 18:43. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTgXiYe6sVc

CloseESSAY

Heather Igloliorte, Amy Prouty and Charissa Von Harringa

Throughout his illustrated poem “My Heart is in My Home,”1 famed Sámi poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää—Áillohaš, in Sámi—ardently upholds the integrity of Indigenous life, arguing for both Sámi rights and Sámi personal and collective responsibility to the land and water. In so doing, Áillohaš, like countless Indigenous literary figures around the world, underscores the lpivotal role of words, language, writing, and poetry as sovereign resources of decolonization—acts of resistance and reclamation against colonially inherited forms of domination, be they cultural, political, psychological, economic, legal, or ideological.

The exhibition Among All These Tundras, its title drawn from this same poem by Áillohaš, features contemporary art by twelve Indigenous artists from around the circumpolar world. The regions from which they hail—throughout Inuit Nunaat and Sápmi—share histories of colonialism and experience its ongoing legacies today. These lands are also connected by rapid movements of cultural resurgence and self-determination, which, expressed via language, art, and even the land itself, reverberate throughout the Arctic.

- Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, “My Home is in My Heart” (1985), in Ruoktu váimmus [Trekways of the Wind] (Norway: DAT, Kautokeino, 1994).

The complete essay written by Heather Igloliorte, Amy Prouty and Charissa Von Harringa can be viewed and downloaded in the Texts and Documents section. A printed version is also available at the Gallery.

Close“ᐊᖕᖏᕋᑦᑎᓐᓂ ᓄᓇᒥ ᐃᓂᖃᖅᐳᒍᑦ”: ᖃᓪᓗᓈᑎᑑᓐᖏᑦᑐᖅ ᐱᓕᕆᖃᑦᑎᒌᖕᓂᖅ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᑉ ᑲᔾᔨᐊᓂ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ

ᕼᐃᑐ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᐅᖅᑎ, ᓴᕆᔅᓴ ᐹᓐ ᕼᐃᐅᓕᒐ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᐃᒥ ᐳᕉᑎ

ᑕᒪᐅᓐᓇ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔭᒥᒍᑦ ᑕᐃᒎᓯᑦ “ᐆᒪᑎᒐ ᐊᖕᖏᕐᕋᓃᑦᑐᖅ,”1— ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᓵᒥ ᓂᐅᔅ-ᐊᔅᓚᒃ ᕚᑭᐊᐹᐊᐃᓗᕼᐋᔅ, ᓵᒥᐅᑎᑐᑦ — ᖃᐅᔨᒪᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖅ ᑎᒍᒥᐊᖅᑕᖓ ᓄᓇᖅᑲᖅᑳᖅᓯᒪᔫᒐᒥ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᓂ, ᐊᐃᕙᐅᑎᓕᒃ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᒃ ᓵᒥᒃᑯᑦ ᐱᔪᓐᓇᐅᑎᒃᓴᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓵᒥ ᓄᓇᖅᑲᖅᑳᖅᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᒪᐃᑕ ᐱᔭᒃᓴᖏᑦ ᓄᓇᒧᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᒪᕐᒧᑦ. ᑕᐃᒪᓐᓇᐅᓪᓗᓂ, ᐊᐃᓗᕼᐋᔅ, ᐊᒥᓱᒻᒪᕆᐋᓗᒃᑎᑐᑦ ᓄᓇᖅᑲᖅᑳᖅᓯᒪᔪᓂ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᑎᐅᔪᖅ ᓇᓂᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᒥ, ᑎᑎᕋᖅᐹ ᐃᐱᕗᑕ ᐃᓂᖓ ᑕᐃᒎᓯᕐᑎᒍᑦ, ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕐᒥᒍᑦ, ᑎᕋᖅᖢᒍ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᐃᒎᓯᓕᐊᕆᓯᒪᓪᓗᒍ ᓄᓇᖁᑎᒋᔭᒥ ᑭᓱᖏᒃ ᖃᓪᓗᓇᐃᖓᔪᓐᓃᖅᑎᓯᒪᓪᓗᒋᑦ — ᒪᓕᒍᒪᓐᖏᑦᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᑎᖅᑎᑦᑎᓂᖅ ᐱᔪᓐᓇᕐᓂᕐᒥᖕᓂᒃ ᑖᒃᑯᓇᖓᑦ ᖃᓪᓗᓈᓂ ᑕᒪᐅᓐᓇ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᒃᑯᑦ, ᐱᐅᓯᑐᖃᕐᓃᑲᓗᐊᕈᑎ, ᓂᕈᐊᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᒐᓗᐊᕈᑎ, ᐃᓱᒪᓕᕆᔨᐅᒐᓗᐊᕈᑎ, ᑮᓇᐅᔭᑎᒍᑦ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᑎᑦᑎᓕᐅᒐᓗᐊᕈᓂ, ᒪᓕᒐᓕᕆᓂᐅᒐᓗᐊᕈᓂ, ᐅᒡᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ ᐃᓱᒪᓕᐅᕆᔨᐅᒐᓗᐊᕈᓂ.

ᐅᑯᐊ ᓴᕿᔮᖅᑐᑦ ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᒃᑯᐊ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᐃᑦ, ᐊᑎᖃᖅᑐᖅ ᐋᕿᒃᑕᖓ ᑖᑉᓱᒪ ᐊᐃᓗᕼᐋᔅ, ᓴᕿᔮᖅᑐᑦ ᒫᓐᓇᐅᔪᖅ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ 12 ᓄᓇᖅᑲᖅᑳᖅᓯᒪᔪᒃ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᖅᑎᑦ ᓇᑭᑐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᓄᓇᕐᔪᐊᑉ ᑲᔾᔨᐊᓂ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᓂᑦ. ᐅᑯᐊ ᐊᕕᒃᑐᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐅᑯᐊ ᐊᐱᕙᒃᑐᑦ — ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᖏᓐᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓵᑉᒥ — ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅᐸᒃᑐᑦ ᖃᓪᓗᓈᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᑐᖅᓯᔪᑦ ᐳᐃᒍᓇᓐᖏᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐃᓅᓯᕐᒥᖕᓂ ᐅᓪᓗᒥᒧᑦ. ᐅᑯᐊ ᓄᓇᐃᑦ ᑲᑎᖓᔪᑦᑕᐅᖅ ᐱᐊᓚᔪᒻᒪᕆᐋᓗᒃᑯᑦ ᓄᒃᑕᖅᖢᑎᒃ ᐱᐅᓯᑐᖃᕐᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᕙᓪᓕᐊᔪᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓇᖕᒥᓂᖅ ᐊᐅᓚᑦᑎᔪᓐᓇᓕᕐᓂᖅ, ᐅᑯᐊᓗ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᐅᔪᑦ ᑕᒪᐅᓐᓇ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᓕᕆᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᖅᓯᒪᔪᓕᕆᓂᒃᑯᑦ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᒪᓐᓇᑦᑕᐅᖅ ᓄᓇᑎᒍᑦ, ᐅᖃᖅᑕᐅᔪᑦ ᑖᒃᑯᐊᑦᑕᐃᓐᓇᐃᑦ ᓇᐅᒃᑯᑐᓐᐃᓐᓇᖅ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ.

The complete essay written by Heather Igloliorte, Amy Prouty and Charissa Von Harringa can be viewed and downloaded in the Texts and Documents section. A printed version is also available at the Gallery.

CloseSUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Arngna’naaq, Ruby, Jack Butler, Sheila Butler, Patrick Mahon, and William Noah, eds. Art and Cold Cash. Toronto: YYZBOOKS, 2009.

Hansson, Heidi and Anka Ryall, eds. Arctic Modernities: The Environmental, the Exotic and the Everyday. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017.

Helander, Elina and Kaarina Kailo, eds. No Beginning, No End: The Sámi Speak Up. Edmonton: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, 1998.

Igloliorte, Heather. “Curating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Inuit Knowledge in the Qallunaat Art Museum.” Art Journal 76, no. 2 (2017): 100-113.

Ipellie, Alootook. “The Colonization of the Arctic.” In Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives in Canadian Art, edited by Gerald McMaster and Lee-Ann Martin, 39-57. Hull, QC: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1992.

Karetak, Joe, Frank Tester, and Shirley Tagalik, eds. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: What Inuit Have Always Known to Be True. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2017.

Lunstroem, Jan-Erik. “Contemporary Sámi Art And Design.” Stockholm: Arvinius + Orfeus Publishing, 2015.

MacKenzie, Scott, and Anna Westerståhl Stenport, eds. Films on Ice: Cinemas of the Arctic. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

Stewart, Michelle. “Of Digital Selves and Digital Sovereignty: Of the North.” Film Quarterly 70, no. 4 (Summer 2017): 23-38.

Thibault, Martin. De la banquise au congélateur : mondialisation et culture au Nunavik. Québec : Presses de l’Université Laval, 2003.

Valkeapää, Nils-Aslak, Greetings from Lappland: The Sámi-Europe’s Forgotten People. London: Zed Press, 1983.

– – – – -. “My home is in my heart.” Alternative 4, no. 2 (2008): 176-177.

Williams, Lisa. “Canada, the Arctic, and Post-National Identity in the Circumpolar World.” The Northern Review, no. 33 (Spring 2011): 113-131.

CloseVisit the Audio | Video section to access the audiovisual documentation of our public programs in conjunction with the exhibition.

Close