July 1 to 31, 2025

Xinyue Zhang

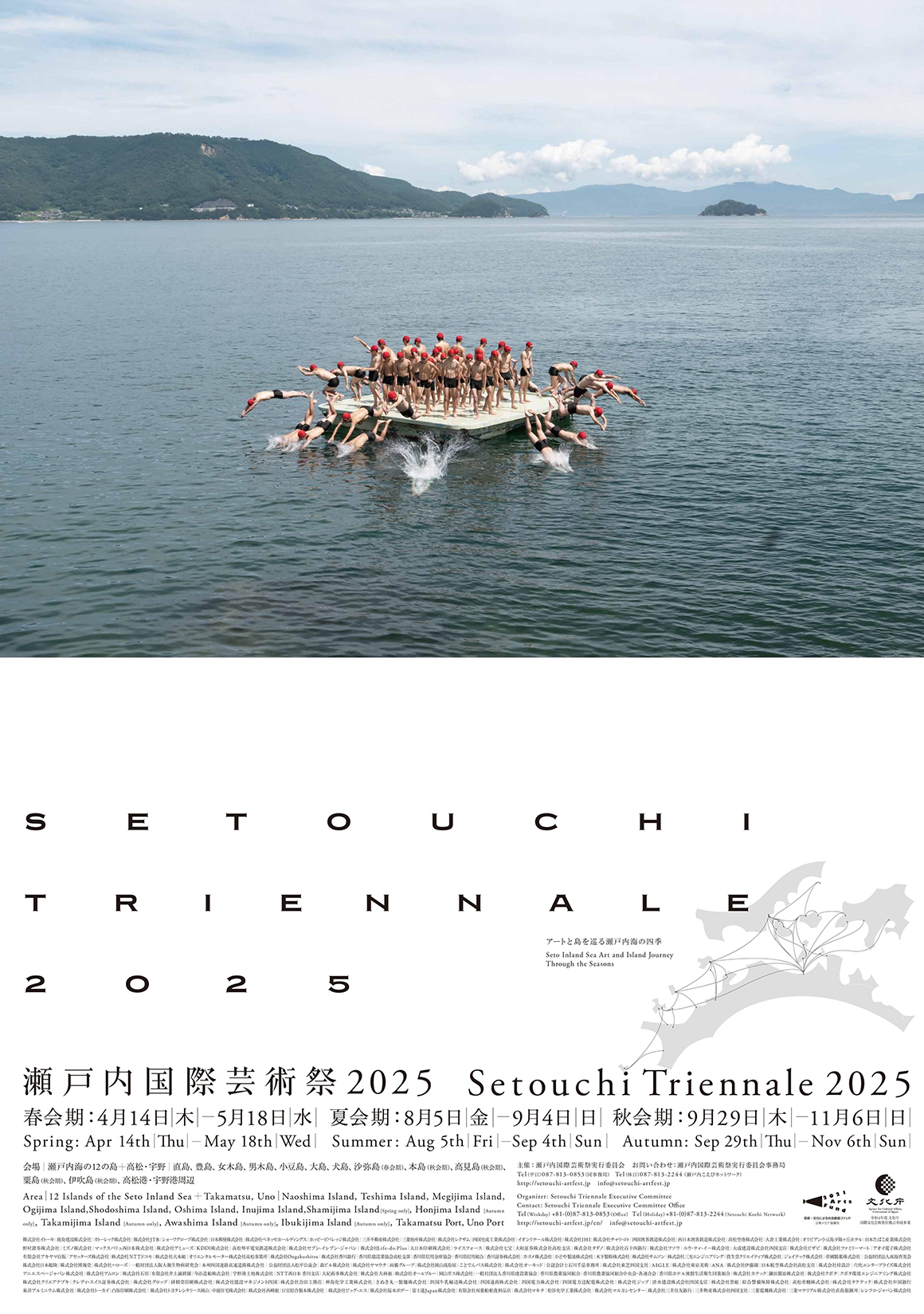

1. The Setouchi Triennale

Read more

“The Setouchi Triennale is a renowned contemporary art festival held every three years across 17 islands and coastal areas in Japan’s Seto Inland Sea. Running this year from April 18 to November 9, it unfolds over three seasonal sessions—spring, summer, and autumn—allowing visitors to experience the region’s diverse landscapes and cultures. Under the theme “Restoration of the Sea,” the festival aims to revitalize local communities through site-specific artworks that harmonize with the natural environment and heritage of each locale. Notable venues include Naoshima, Teshima, and Shodoshima, featuring installations by both Japanese and international artists. The Triennale offers a unique journey where art, nature, and daily life converge, fostering meaningful exchanges between artists, residents, and visitors.”

Description of Setouchi Triennale adapted from website by Xinyue Zhang, see https://setouchi-artfest.jp/en/about/mission-and-history/ for more information.

Close2. Shinro Ohtake, MECON, 2013

Megijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Stepping into MECON by Shinro Ohtake feels like stumbling upon a forgotten jungle dream, where wild nature and industrial remnants converge in ecstatic disarray. Tucked beside an old school building on Megijima island, this sculptural garden is a dense collage of life and material: ceramic tile mosaics, rusted boat parts, fragments of neon, and a towering palm tree that once belonged to the island itself.

What struck me most was the sheer vitality of the place. Tropical greenery grows boldly through metal cages, wrapping itself around mechanical structures as if reclaiming them. Leaves burst through the gaps with fearless energy, transforming containment into expression. The work vibrates with a raw, untamed life force—a secret garden where chaos feels sacred.

Ohtake’s signature is everywhere, yet never overpowering. MECON doesn’t ask to be understood in a linear way, it invites you to feel your way through, to notice textures, contrasts, and the delicate tension between nature’s persistence and human imagination.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

3. Nicolas Darrot , Navigation Room, 2022

Megijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read moreVideo: Xinyue Zhang

In Navigation Room, Nicolas Darrot constructs a cosmos in miniature—a kinetic planetarium where time, tide, and celestial rhythms unfold through a choreography of moving parts. At its heart is a music box that plays compositions for each month of the year, synchronized with a delicate navigational chart made of shells and twigs. This handmade map, inspired by Micronesian stick charts, suggests an ancient yet speculative astronomy, tracking the sun’s dimming light and the invisible pulse of the stars.

In 2025, a new layer has been added: a lunar calendar aligned with the phases of the moon, deepening the work’s connection to cycles of time and intuition.

Stepping into this room, I felt visually overwhelmed in the best possible way. Every mechanism was in motion—subtle, intricate, alive. It became impossible to take in everything at once. I found myself staying longer than I expected, watching, then re-watching, letting my attention drift from one device to another. The space invites return and reconsideration. Navigation Room is less about observation than about orbit—pulling you into its own slow, planetary rhythm.

Close4. The Cabin Company, Mekochan: Old School Bookstore, 2025

Megijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Tucked inside a repurposed school building on Megijima island, Mekochan: Old School Bookstore transforms a classroom into a whimsical—and slightly uncanny—picture book world. Created by Kentaro Abe and Saki Yoshioka, the artist duo behind The Cabin Company, the installation invites visitors into a narrative realm shaped by vibrant colours, bold characters, and a sense of childlike wonder tinged with surrealism.

At the centre of the room sits Mekochan, a huge doll figure with wide eyes and a heavy backpack. My first impression was a subtle sense of eeriness—her presence both doll-like and haunting. But as I spent more time in the space, that feeling shifted. Immersed in the visual language of the room, I began to see through her eyes. I imagined myself as Mekochan, wandering through this tiny, magical bookstore, surrounded by stories and textures that stretched the limits of memory and imagination.

Old School Bookstore is more than an installation—it’s a portal into another self, another childhood, another way of seeing.

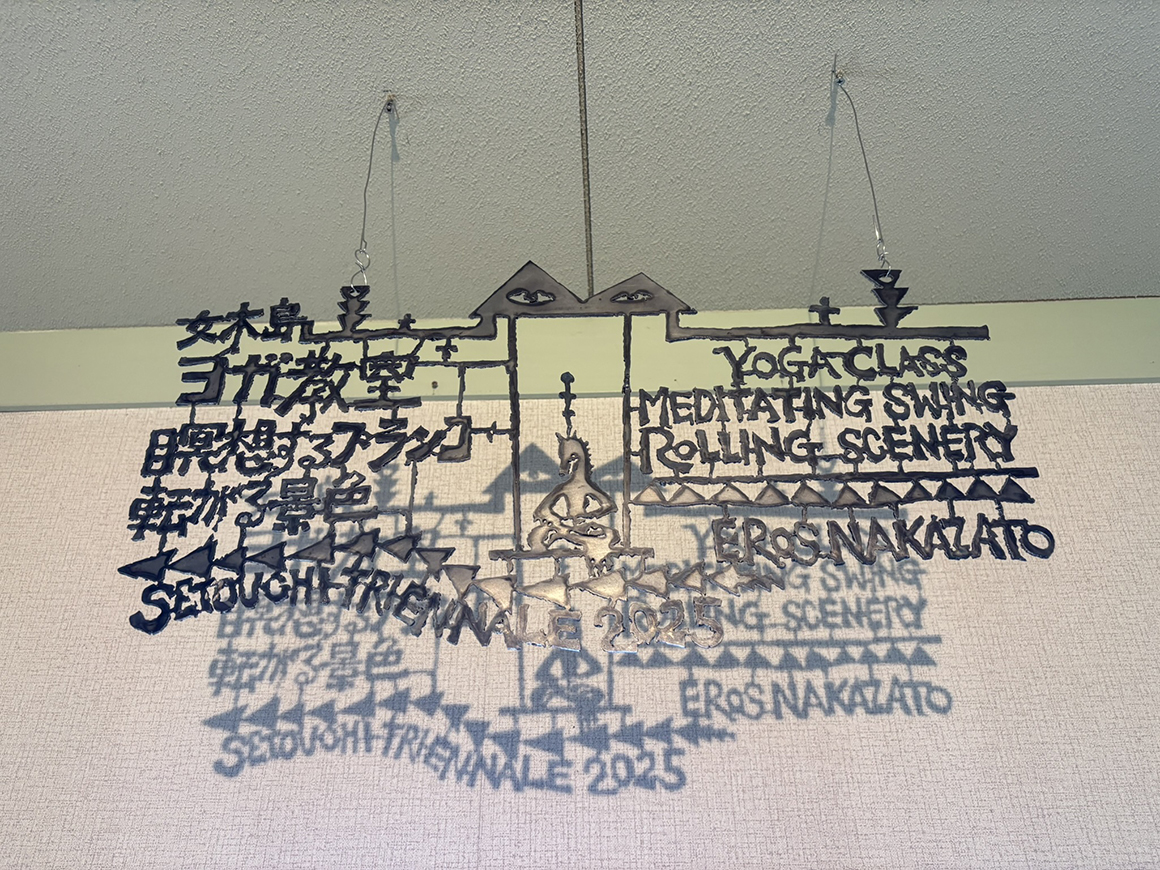

Close5. Eros Nakazato, Yoga Class – Meditating Swing, Rolling Scenery, 2025

Megijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read moreVideo: Xinyue Zhang

Part of the Little Shops on the Island series, Yoga Class – Meditating Swing, Rolling Scenery by Eros Nakazato reimagines wellness as an immersive art experience. The work offers more than just a space to move—it’s a site where the body, light, and landscape are gently aligned. Facing Mount Yashima across the Seto Inland Sea, a swing hangs at the centre of the room, inviting visitors to breathe, sway, and contemplate.

This installation quickly became one of my favourites. Nakazato fuses retro charm with cyber-futurism, utilizing intricate mechanical structures and fantastical, crystal-like spheres to create a yoga space that feels simultaneously grounded and otherworldly. Sitting on the swing in the centre, I gazed out the window toward the shimmering sea, and for a moment, I felt as if I had wandered into a contemporary Peach Blossom Spring. Time slowed down, and the line between everyday life and dream gently dissolved.

Yoga Class is more than a metaphor for balance—it’s an embodiment of the island’s quiet vitality and the imagination it inspires.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

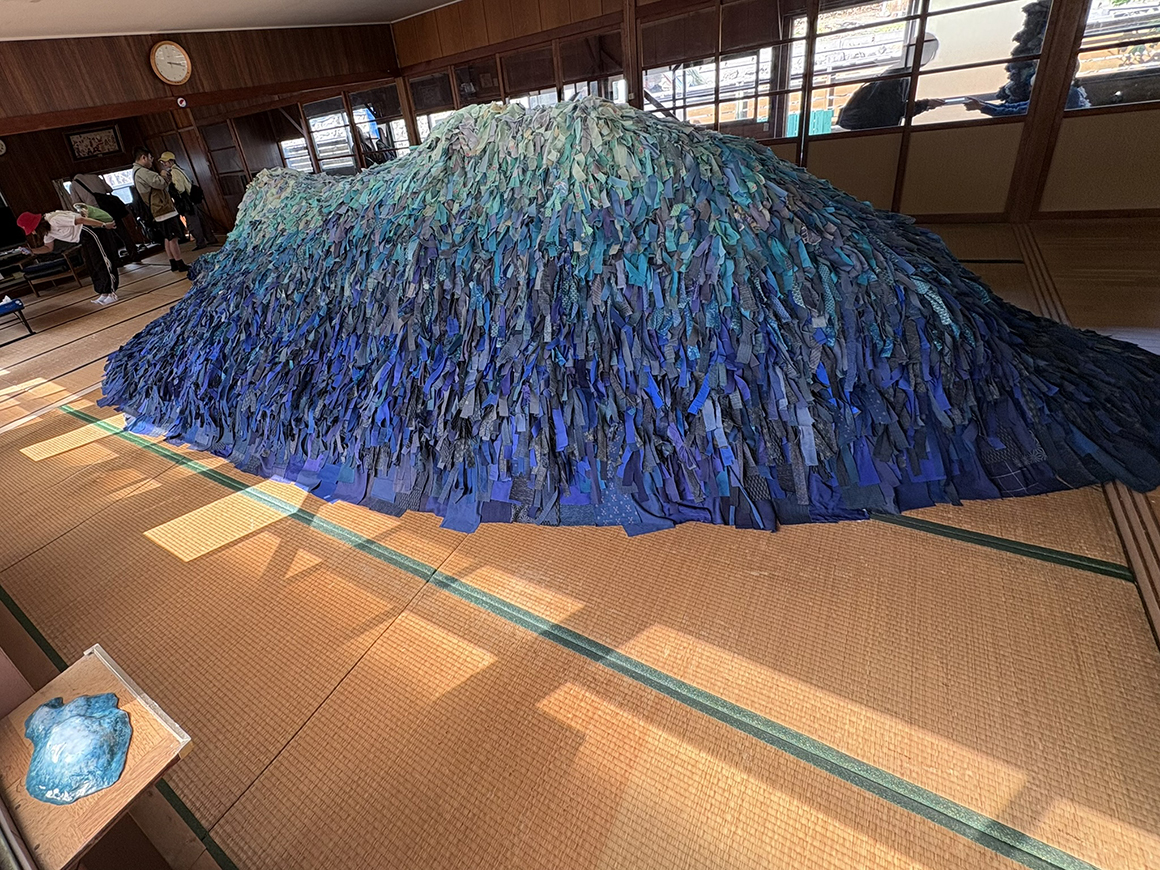

6. Emilie Faif, Our Island, 2025

Ogijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Emilie Faif’s Our Island is not just a sculpture—it’s a fabric map of memory, woven with the textures of daily life on Ogijima. Shaped like the island itself, the piece is constructed from indigo-dyed textiles, including traditional kuruma-ori and shijira-ori weaves, along with recycled clothing and donated fabric from residents. With fewer than 200 inhabitants, the entire island quite literally contributes to the work—thread by thread, life by life.

The journey to the installation is slow and considered. A sequence of thresholds—road, outer corridor, inner passage, glass doors—delays immediate encounter and builds anticipation. When I entered, I realized the space felt less like a gallery than a gathering place. It resembled a seniors’ activity room, still holding the rhythm of everyday use: a kettle quietly resting, a television in the corner, a game of Go left mid-play, and a cat curled contentedly on the couch, perhaps waiting for the next visitor to offer a gentle hello.

In that moment, I understood something essential: Our Island doesn’t separate art from life—it affirms that they are the same. This sculpture, nestled within a living space, glows not with monumentality but with familiarity. It is a celebration of community, memory, and the quiet brilliance of ordinary things.

Close7. Keisuke Yamaguchi, Walking Ark, 2013

Ogijima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Perched at the edge of a seawall, Walking Ark by Keisuke Yamaguchi brings a whimsical vision to life—a four-legged vessel inspired by Noah’s Ark, poised to stride boldly into the Seto Inland Sea. Painted in crisp white and ocean blue, its four peaked “hulls” resemble sails or mountain ridges, giving the impression that the ark is not only walking but carrying the landscape with it.

There’s something irresistibly charming about this piece. As soon as I saw it, I couldn’t help but pose with it, mirroring its confident march toward the water. Its rhythm and formation evoke a band of ocean-loving sailors, ready to embark on their next great adventure. The work invites play, movement, and a bit of childlike imagination.

Walking Ark doesn’t sit still as a monument—it strides forward, carrying our fantasies of travel, togetherness, and the wide, waiting sea.

Close8. Yayoi Kusama, Red Pumpkin, 2006

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

For many visitors, Yayoi Kusama’s Red Pumpkin is the first encounter with art on Naoshima—standing proudly at Miyanoura Port, it greets each arriving ferry like a surreal lighthouse. According to the artist, a red sunbeam traveled across the universe, only to transform into this bold, spotted form resting in the Seto Sea.

I first saw it from the ferry deck, and even from a distance, it radiated a magnetic presence. But walking up to it was a surprise—the sculpture is larger than it first appears, playful yet monumental. Its vivid red surface contrasts dramatically with the soft blues and greens of sea and mountain, as if it were dropped into the landscape from another world.

What’s most delightful is its interactivity. Kusama didn’t just make a sculpture to look at—she created something to enter. Crawling inside the pumpkin and peering out through its spotted windows, I found myself smiling. The sea looked different from inside: framed, filtered, and gently surreal. A small moment of joy and altered perspective.

Close9. Tadao Ando, Benesse House Museum, 1992

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Situated quietly on the slopes of Naoshima, Benesse House Museum is as much an artwork as the masterpieces it houses. Designed by Tadao Ando and opened in 1992, the building blends seamlessly into its coastal environment — its smooth concrete walls nestled among trees, anchored against the vast backdrop of sky and sea.

The 2025 exhibition features iconic Western artists such as Frank Stella, but even before entering the galleries, one feels the gravity of Ando’s architecture.

For me, the museum itself was the most powerful experience. Its cool grey geometry does not dominate the landscape; rather, it echoes it. The walls, cast in exposed concrete, rise with quiet confidence—solid, grounded, and deeply aware of their surroundings. Walking through its passages, with sudden views of the ocean or pockets of filtered sunlight, I felt enveloped by something both monumental and gentle.

Benesse House reminds us that architecture, at its best, doesn’t just hold art—it becomes part of the emotional and aesthetic experience.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

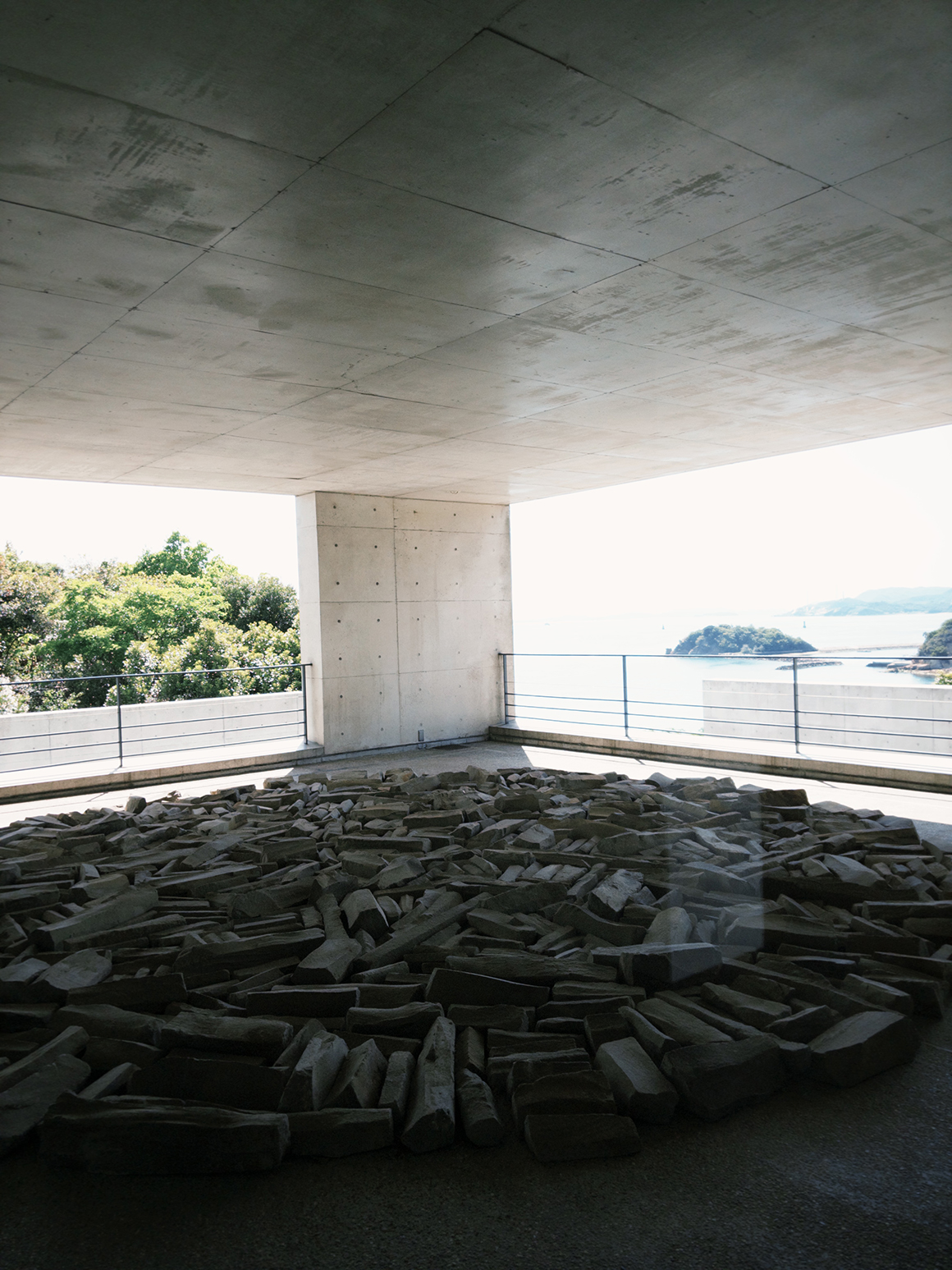

10. Lee Ufan and Tadao Ando, Lee Ufan Museum, 2010

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

The Lee Ufan Museum is the result of a quiet yet powerful dialogue between artist Lee Ufan and architect Tadao Ando. Carved discreetly into the Naoshima hillside, the building embraces the philosophy of “less is more”—its raw concrete walls and natural light guiding visitors toward stillness, reflection, and slowness.

Lee’s installations don’t simply reside in the museum—they extend it, breathe through it, and anchor it to the land. At the entrance, a single towering pillar rises like a sundial—solemn, enduring, and monument-like. It evokes the passage of time with almost ceremonial gravity.

Toward the sea, another work waits in silence: a gate-like structure standing between the mountain and the ocean. It resembles a portal—perhaps to memory, perhaps to the future. Its frame captures not only the shifting landscape, but something intangible: the moment you realize art, space, and nature have converged.

This museum is not a place to rush through. It’s one to enter slowly, and leave slowly, carrying the echo of wind, stone, and time.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

11. Tadao Ando, Chichu Art Museum, 2004

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Of all the spaces I encountered during my time in Setouchi, Chichu Art Museum offered the most surreal and otherworldly experience. Designed by Tadao Ando and embedded in the hillside of Naoshima, this underground museum is both fortress and shrine—built to protect the surrounding landscape while creating a space for light, silence, and total immersion.

You’re told not to take photographs upon entering the main exhibition zones. At first, this restriction feels curious. But as you step deeper inside, it becomes clear: no lens could ever fully capture what this space intends for you to feel.

To reach the museum’s heart, you pass through a long, austere corridor, descending into the mountain as if entering the mind of the architecture itself. From there, you arrive at an open-air courtyard—Ando’s signature moment of spatial pause—before slowly ascending along towering concrete walls toward a hidden light source. This quiet climb ends at the threshold of the first gallery.

Inside, the experience becomes almost sacred. Works by Claude Monet, James Turrell, and Walter De Maria are not simply shown—they envelop you.

Turrell’s installation in particular left me speechless. What appears to be a glowing void reveals itself to be precisely calibrated light, sculpted with an invisible hand. As I stood before it, I lost all sense of depth, of space, even of self. The light didn’t just illuminate the room—it completely redefined it. It was not a visual experience, but a physical one, like standing inside an idea.

Even the staff heightens the surreal quality. Dressed in white lab coats, they drift silently through the dim corridors like caretakers of a temple—part scientist, part monk. In this stark, grey underworld, their presence feels both unsettling and profoundly reverent.

Chichu Art Museum is not just an art destination—it’s a passage through matter and meaning. You don’t simply view art; you surrender to it.

If you ever have the chance to visit in person, I cannot recommend it enough. This is something that has no photo, and that no description can replace.

Close12. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery: Time Corridors, 2022

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Time Corridors is more than a gallery—it’s a conceptual bridge across decades of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s practice. Situated in Naoshima, where his creative journey first began, the space offers a deep encounter with the full scope of Sugimoto’s work: photography, design, sculpture, and philosophy. It also serves as a spiritual and artistic connection to his Enoura Observatory in Odawara, which many consider his ultimate statement.

The exhibition moves with the precision of memory: linear, yet nonlinear; architectural, yet deeply meditative. Light and shadow guide you through spaces that feel outside of time.

What struck me most was the way Time Corridors echoed and activated another work I had visited on Naoshima. Standing within this gallery, and then again inside the other mirrored site, I felt disoriented—in the most beautiful way. It was as if time folded in on itself, and I was both here and elsewhere, then and now.

The experience was not about comparing two artworks but about feeling their resonance across space. Sugimoto doesn’t just present images—he collapses distance, challenges chronology, and gently reminds us that perception is a shifting, fragile thing.

Time Corridors left me suspended in a state of thoughtful confusion, and I loved it.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

13. Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden, 2022

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Installed in a tranquil valley long regarded as sacred ground, Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden becomes both a spectacle and a mirror, inviting not only sight but reflection.

Dozens of mirrored spheres scatter across the space, some glinting under open sky, others shimmering quietly in the subdued light indoors. True to Kusama’s signature style, the repetition feels obsessive, beautiful, and slightly disorienting. The landscape moves through each orb: the sky, the trees, and the viewer’s own face reflected again and again.

I was immediately struck by the visual intensity—the metallic orbs catching sunlight outside, then transitioning into pools of shadow and light indoors. It’s a garden of echoes, and in each glimmering surface, you confront yourself. The effect is almost spiritual. Amid breathtaking beauty, the work gently pushes you inward.

Paired with Tsuyoshi Ozawa’s Slag Buddha 88, Narcissus Garden is not only a visual installation—it becomes a site of quiet prayer and environmental reckoning. Together, these works honour the land, the industrial past, and the human impulse to find meaning in repetition.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

14. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Art House Project, Go’o Shrine, 2002

Naoshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

As part of the Art House Project, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Go’o Shrine bridges the spiritual and the material with a gesture both delicate and monumental. Restored from a historical Shinto shrine, the site now features a luminous glass staircase that connects an underground stone chamber to the world above, linking earth to sky, past to present.

Having just experienced Sugimoto’s Time Corridors, I approached Go’o Shrine with a heightened sensitivity to time, space, and the uncanny poetry of transition. But nothing prepared me for the moment of descent.

We were handed a flashlight and asked to proceed alone, one by one, through a narrow stone passage just wide enough for a single person. The darkness was intimate, pressing. At the end of the corridor, lit only by the beam of our flashlight, the crystal steps revealed themselves: fragile, translucent, almost breathing with light. It was as if time itself had slowed into particles.

The return journey held a different kind of wonder. As we turned to walk back through the same narrow corridor, natural light, faint, silvery, and sea-touched, began to filter in. It wasn’t just a return to the surface, but an emergence. I felt like I was crossing a threshold between two realms, reentering the world through a space now made sacred.

Go’o Shrine is more than a restored structure—it’s an experiential axis, where architecture, ritual, and light align.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

15. Rei Naito and Ryue Nishizawa, Teshima Art Museum, 2010

Teshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

I arrived at Teshima Art Museum on a rainy day, and I can’t imagine a more perfect moment. Designed by architect Ryue Nishizawa and artist Rei Naito, the museum sits nestled in a terraced hillside, overlooking the Seto Inland Sea. The structure resembles a giant concrete shell—organic, open, quietly monumental. That day, rain clung to its surface, dyeing the concrete with deep, shifting shades of grey. The scent of wet earth, the sound of distant waves, the soft whisper of sea breeze—it all conspired to still the mind.

Inside, the experience shifts from architecture to atmosphere. The museum has no walls in the conventional sense—only a continuous, undulating space punctuated by two large circular openings in the ceiling. Through them, light, wind, and rain enter without permission. You sit on the bare floor, barefoot like everyone else, and look up. Leaves from a nearby tree tremble in the wind. Occasionally, a raindrop makes it all the way through.

And then there’s Matrix—the artwork by Rei Naito that doesn’t hang, doesn’t stand, but emerges. Tiny drops of water, almost invisible at first, rise from discreet pores in the floor. They gather slowly, delicately, merging into one another like thought forming in silence. The droplets never follow the same path twice. They shimmer, wander, and reflect light like living brushstrokes. No sound but the weather. No movement but the earth breathing.

There are no photos allowed here—and for good reason. Any attempt to capture this place with a camera would flatten it. Teshima Art Museum isn’t something you document. It’s something you inhabit.

And after that silence, a small delight: the museum café serves exceptional coffee and soft, chewy bagels. Sitting with a warm cup, surrounded by the sea and fields, the quiet lingers a little longer.

16. Christian Boltanski, Les Archives du Cœur, 2010

Teshima – Setouchi Triennale 2025

Read more

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Tucked into a secluded bay on the far side of Teshima, Les Archives du Cœur is a work of immense intimacy housed in a structure that feels both remote and sacred. Created by Christian Boltanski, the project is an ongoing archive of heartbeats gathered from across the world—a fragile, rhythmic record of lives, preserved one pulse at a time.

I arrived during a storm. Rain swept across the hills, and the wind howled against the coastline. By the time I reached the modest black cabin, the sky had darkened into something cinematic. The building—low, dark, nearly blending into the sea—gave off an atmosphere that was at once magnetic and slightly unsettling. It felt less like entering a gallery and more like stepping into an emotional threshold.

Inside the main chamber, a solitary yellow light hung from the ceiling, casting a muted glow. It blinked softly in sync with a recorded heartbeat, each flash a quiet declaration of life. The sound filled the room, thick and resonant, echoing like a sacred chant. In that moment, surrounded by darkness, salt air, and a stranger’s heart, I felt life distilled to its most essential rhythm. It was beautiful. It was eerie. It was humbling.

I didn’t record my heartbeat that day, but visitors are invited to do so in a separate room, becoming part of this global constellation of human presence. It’s an act of preservation, a quiet contribution to a shared archive of vulnerability and existence.

Photography is not permitted inside, and rightly so. This experience is not meant to be captured, only felt.

Visitor tip: This is a powerful, sometimes haunting experience. If you’re sensitive to darkness, solitude, or silence, go gently. But do go. It lingers with you long after you leave.

Photo: Xinyue Zhang

Throughout the month of July, the Gallery invites you to discover the travel diary of the 2025 Ann Duncan Award recipient, Xinyue Zhang. Follow her journey on our Instagram account, where we’ll share highlights from her trip to the Setouchi Triennale in Japan. At the same time, the Gallery will present Zhang’s texts in their entirety as well as a larger number of images on our website.

Xinyue Zhang is an art history student at Concordia University and the 2025 recipient of the Ann Duncan Travel Award. From May 7 to 11 2025, she traveled to Japan to explore the Setouchi Triennial Art Festival, visiting site-specific installations across the islands. Her journey focused on experiencing contemporary art in dialogue with landscape, memory, and community.

The Ann Duncan Award is an undergraduate award that supports international travel and tuition, given every two years alternating between Studio Arts and Art History students. In 2025, the Travel and Tuition Award was given to an undergraduate student registered as a full-time student in Art History.