tsi iotnekahtentiónhatie (Tiohtià:ke)

November 19, 2025 to February 7, 2026

tsi iotnekahtentiónhatie (Tiohtià:ke)

Hannah Claus

Curator: Nicole Burisch

Artist

Hannah Claus (Kenhtè:ke | Tyendinaga Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte) is a Kanien’kehá:ka | English visual artist who engages with material and sensorial relationships to express Kanien’kehá:ka epistemology and ontology. Recipient of the Eiteljorg Fellowship (2019) and the Prix Giverny (2020), Claus’s recent group exhibitions include Contextile: Biennial of Contemporary Textile Art (Guimarães, Portugual) and the North American touring exhibition, Radical Stitch. Her solo exhibition, tsi iotnekahtentiónhatie – éntie nonkwá:ti – where the waters flow – south shore is currently showing at Canada House Gallery (London, England). She is an Associate Professor in Studio Arts at Concordia University in Tiohtià:ke | Montreal.

CloseExplore

The city and the island most commonly referred to today as Montréal have had a long human history predating the arrival of French settlers who colonized the land and, in doing so, bestowed this name. Oral histories from various Indigenous nations, as well as archeological evidence, situate this place historically as a site of diplomacy and encounter of many Indigenous peoples, including the Kanien’kehá:ka, the Wendat, the Anishinaabe, and the W8banaki. From this history, many names were given to this site of encounter, including Tiohtià:ke, an abbreviation of the Kanien’kéha word Teionihtiohtià:kon, meaning “where the group divided/parted ways.” Other names include Mooniyaang in Anishinaabemowin, Molian in Aln8ba8dwaw8gan [W8banaki language], and Te ockiai in Wendat. The island itself has been known as Kawé:note Teiontiakon in Kanien’kéha, meaning “The Place Where the People Divide.”1

The name “Montréal” is said to have first been derived from Jacques Cartier, who climbed the island’s central mountain in 1535 and named it “le mont Royal” [Mount Royal], and later from historiographer François de Belleforest, who, in 1575, first used the form Montréal to describe the city, which became the favoured name even after the formal establishment of the village Ville-Marie in 1642. Samuel de Champlain also referred to the island as Isle de Mont-réal in 1632, replacing the previous name he had used, lille de Vilmenon.

Explore

- How would you describe your relationship to Tiohtià:ke/Montréal as a city? As an island?

- Which of its landmarks are important to you and why?

- How do the works in the exhibition draw from this place’s many histories and its geographies?

Kaniatarowanen, meaning “big waterway,” is one of the names the Kanien’kehá:ka and Skarù:ręˀ (Tuscarora) have given to the St. Lawrence River. Many other Indigenous communities have other names for the river, reflecting their own languages and relationships with it. These include Magtogoek (“the walking path”) in Anishinaabemowin, Wepìstùkwiyaht sīpu in Innu-aimun, Kchitegw (“Great River”) in Aln8ba8dwaw8gan and Lada8anna in Wendat.

The river has long played, and continues to play, an important role as a means of connection between communities, in addition to being a key site for hunting, fishing, and foraging. The many islands that pepper the riverway have also been used for processing caught fish, as well as burials sites. From the early 17th to the mid-19th century, it was one of the main gateways to the North American fur trade, which ended up playing a significant role in the colonial development and expansion of what would become so-called Canada. Kaniatarowanen is also home to many species of marine life including river otters, belugas, fourteen species of whales, and various fish. Along its banks, migratory birds make their seasonal stops and eighty percent of Quebec’s population live along its shores and tributaries, with fifty percent of municipalities drawing their drinking water from the river. It also holds the title of the world’s largest estuary.

Explore

- How does Claus express her relationships with Kaniatarowanen through her artwork?

- As you follow the traces of the river from artwork to artwork, (Kanaiatariio [beautiful big river], 2024 to watersong [Kaniatarowanen – othorè:ke nonkwá:ti], 2025 to reflection on river rock [Blue Nordic], 2003 to the language of the land, 2024) reflect on the histories of the river and your relationship to it. How can we also give thanks to all that it provides us?

- What relationships between sky, land, and water are evoked in these works and where do you see yourself embedded in them?

Meaning “People of the Longhouse,” the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Rotinonshón:ni in Kanien’kéha) was, at its inception, composed of five First Nations which emerged from the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa in Kanien’kéha), brokered by the Great Peacemaker.

From east to west, these nations include the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) – The People of the Flint, Onʌyoteˀa·ká· (Oneida) – The People of the Upright Stone, Onoñda’gega’ (Onondaga) – The People of the Hills, Guyohkohnyoh (Cayuga) – The People of the Great Swamp, and Onöndowa’ga:’ (Seneca) – The People of the Great Hill. In 1722, Skarù:ręˀ (Tuscarora) – The Shirt Wearing People – joined as the sixth nation.

The Great Law of Peace, recorded through a beaded wampum belt, includes a constitution of 117 articles detailing the rights and responsibilities of the peoples it governs, brought forth by the teachings of the Great Peacemaker. Leaders proposing new laws must consider how the laws would affect the people for seven generations, or risk losing their seat. Only Clan Mothers can appoint new leaders, and both the men’s and the women’s councils of each clan had the power to propose laws.

Each nation comprises members of various clans. Within the matrilineal system, children inherit the clan of their mothers. The nine clans include the three land animals – Deer, Wolf, and Bear; the three water animals – Turtle, Beaver, and Eel; and the three sky animals – Snipe, Hawk, and Heron.

Explore

- How does Claus evoke Haudenosaunee cosmologies within her works? Where are there allusions to Indigenous practices, histories, creation stories, etc. within the work?

- How can artworks, including contemporary ones, be used to hold and commemorate ceremonies, relationships, and histories? How is this achieved in Claus’s works?

Wampum belts, traditionally made of shell beads, were and continue to be used by certain Indigenous communities on Turtle Island for ceremonial ornamental, and trade uses. The word is derived from an abbreviation of wampumpeake or wampumpeake, the plural of the combination of the words white and string in Massachusee unontꝏwaok (Massachusett language). Beaded patterns on belts have been used to document and narrate various Haudenosaunee histories, traditions, and laws – notably the 117 articles in the Great Law of Peace. The Kanien’kéha word for wampum is kahionni meaning “river made by hand.”

Notable wampum belts important to Haudenosaunee histories include the Hiawatha Belt, which conveys the unity of the five original nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, as well as the Circle Wampum, composed of fifty equal strands representing the fifty chiefs – each equal and united. One central strand represents the people, while the two entwined strings forming the outer circle represent The Great Peace and The Great Law. In 1701, a Great Peace Treaty Council was held in Montréal between the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations: the resulting treaty was memorialized through the Dish With One Spoon wampum belt depicting a single dish, representing the land to be shared in its centre.

Another important wampum belt is the Two Row Wampum Treaty (Teiohate Kaswenta in Kanien’kéha). Made in 1613, it is a living treaty between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch government, and the first peace treaty of its kind between Onkwehón:we (First Peoples) and Europeans. The treaty affirmed an agreement of mutual respect toward each other’s cultures. The belt is composed of two parallel lines of purple beads, interspersed with bands of white: one purple line representing a Haudenosaunee canoe, and the other a European sailboat, both traveling side by side without interference nor meddling between boats. The analogy suggests having one foot in each boat will lead to capsizing. The three parallel white lines symbolize peace, friendship, and perpetuity.

Explore

- Where in Claus’s works are references to wampum and wampum belts made? Observe her use of repetition and parallel lines across works.

- In what ways do the work reference real geographies, histories, and treaties?

- How can art serve as living documents?

Works

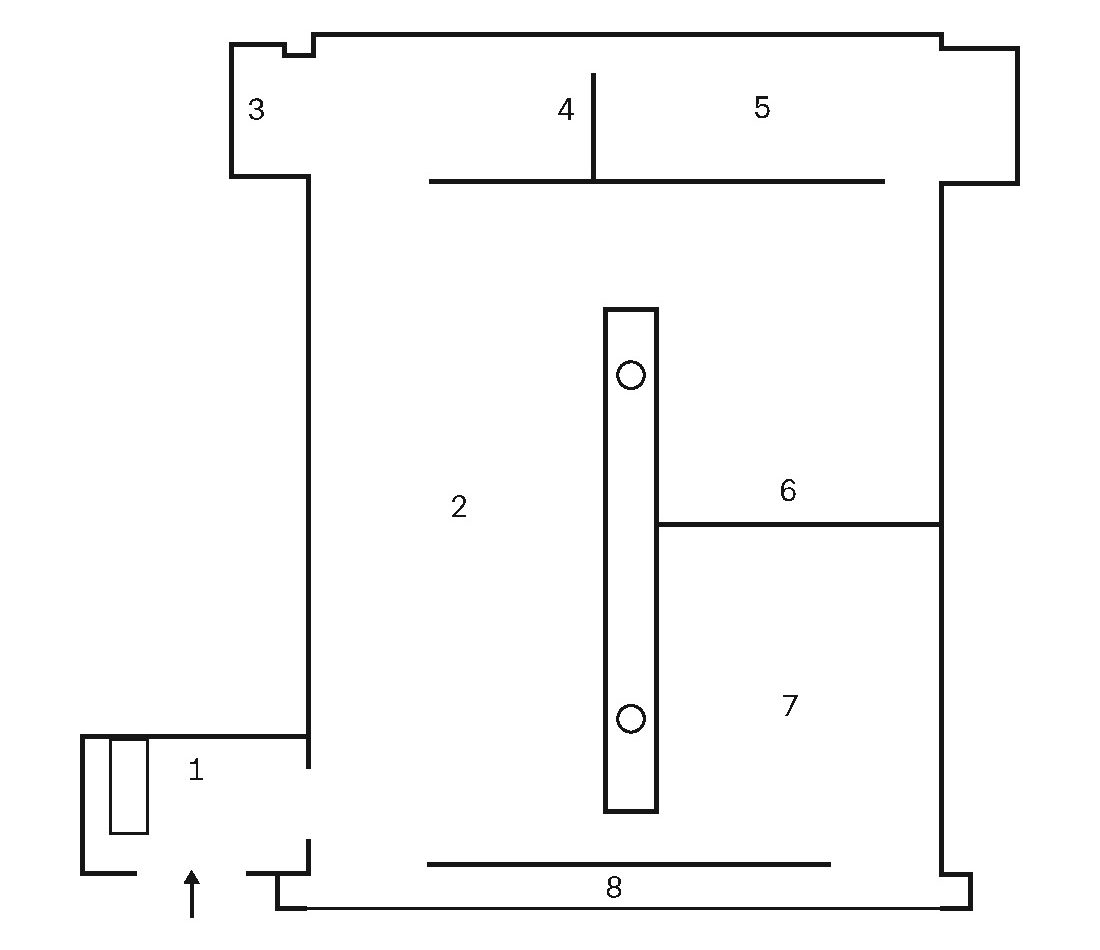

1. Kanaiatariio [beautiful big river], 2024

Audio, 1 min. 13 sec. Sung and composed by Ionhiarò:roks McComber

Courtesy of the artist

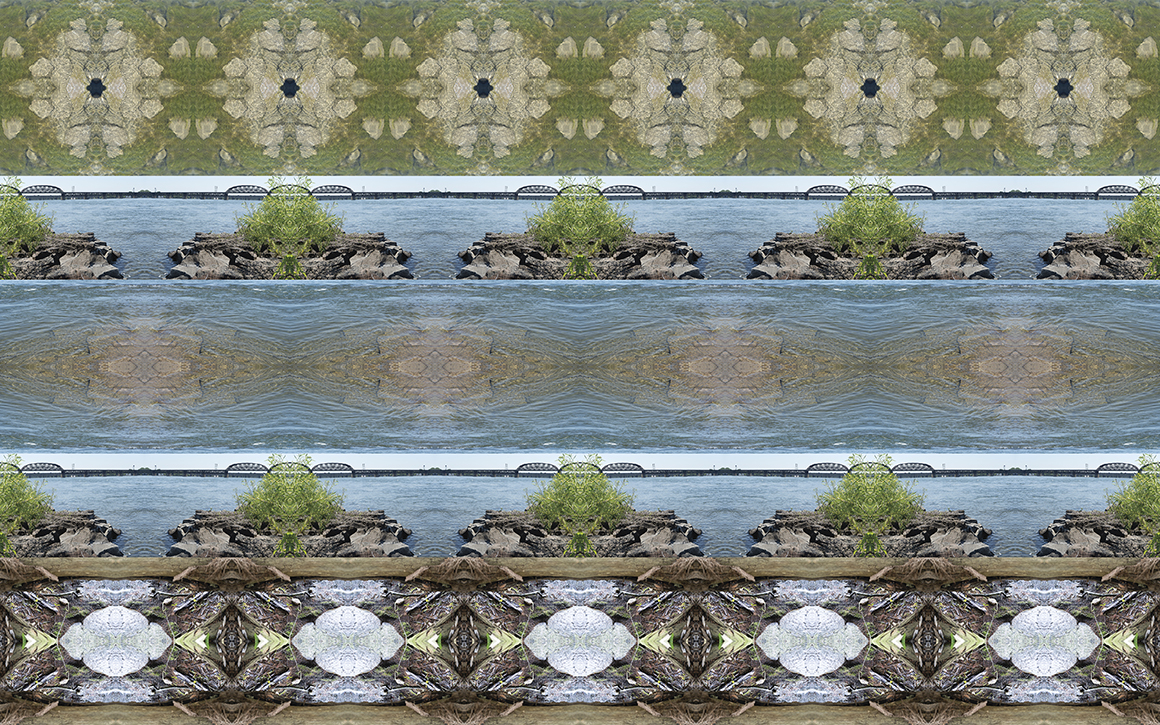

2. watersong [Kaniatarowanen – othorè:ke nonkwá:ti], 2025

Acrylic, thread, glass beads, digital prints on Jetview film, PVA glue 701 × 365 cm Composer of the song: Ionhiarò:roks McComber

Courtesy of the artist

3. iakoròn:ien’s [the sky falls around her], 2020

Single-channel video, 5 min. Video technician: Raohserahà:wi Hemlock

Courtesy of the artist

4. flatrocks 1, flatrocks 2, flatrocks 3, flatrocks 4, 2024

Digital prints facemounted on acrylic sheets 137 × 91.5 cm each

Courtesy of the artist

5. reflection on river rock [Blue Nordic], 2003

Single-channel video with audio, river rocks, 5 min. 40 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

6. skystrip, 2006

Digital print on polypropylene banner, thread, river rocks 165 × 183 × 609 cm

Courtesy of the artist

7. dish, 2025

Acrylic, aluminium, glass beads, thread, digital prints on Jetview film, PVA glue 305 × 305 × 305 cm

Courtesy of the artist

8. the language of the land, 2024

Digital print facemounted on acrylic sheet 152 × 244 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Supplementary ressources

Berthelette, Scott. “Fur Trade Route Networks.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, February 7, 2006. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fur-trade-routes.

Blanchard, David. … “To the Other Side of the Sky: Catholicism at Kahnawake, 1667-1700.” Anthropologica 24, no. 1 (1982): 88. https://doi.org/10.2307/25605087.

Bonaparte, Darren. “Kaniatarowanenneh: River of the Iroquois.” The Wampum Chronicles. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.wampumchronicles.com/kaniatarowanenneh.html.

Cardenas, Yenny Vega. “Rights for the Saint Lawrence River.” Earth Law Center, October 16, 2018. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.earthlawcenter.org/blog-entries/2018/10/rights-for-the-saint-lawrence-river.

Claus, Hannah. “Hannah Claus Interview.” Interview by Dion Smith-Dokkie. Initiative for Indigenous Futures, 2017. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://indigenousfutures.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Transcript_Hannah-Claus-Interview.pdf.

Duhamel, Karine. “The Two Row Wampum.” Canadian Museum for Human Rights, November 14, 2018. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://humanrights.ca/story/two-row-wampum.

Foster, John E., and William John Eccles. “Fur Trade in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 23, 2013. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fur-trade.

Jacobs, Dean M., and Victor P. Lytwyn. “Naagan ge bezhig emkwaan: A Dish with One Spoon Reconsidered.” Ontario History112, no. 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7202/1072237ar.

SNAP Québec. “St. Lawrence Conservation.” Accessed November 10, 2025. https://snapquebec.org/en/our-work/st-lawrence/.

Art Canada Institute – Institut De L’art Canadien. “Two Row Wampum Belt 1613.” Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/war-art-in-canada/key-works/two-row-wampum-belt/.

Ganondagan State Historic Site. “Wampum.” Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.ganondagan.org/wampum.

Oneida Indian Nation. “Wampum: Memorializing the Spoken Word.” Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.oneidaindiannation.com/wampum-memorializing-the-spoken-word/.

Close