April 29 – June 19, 2021

Curator: Paul B. Preciado

Produced with the support of the Frederick and Mary Kay Lowy Art Education Fund

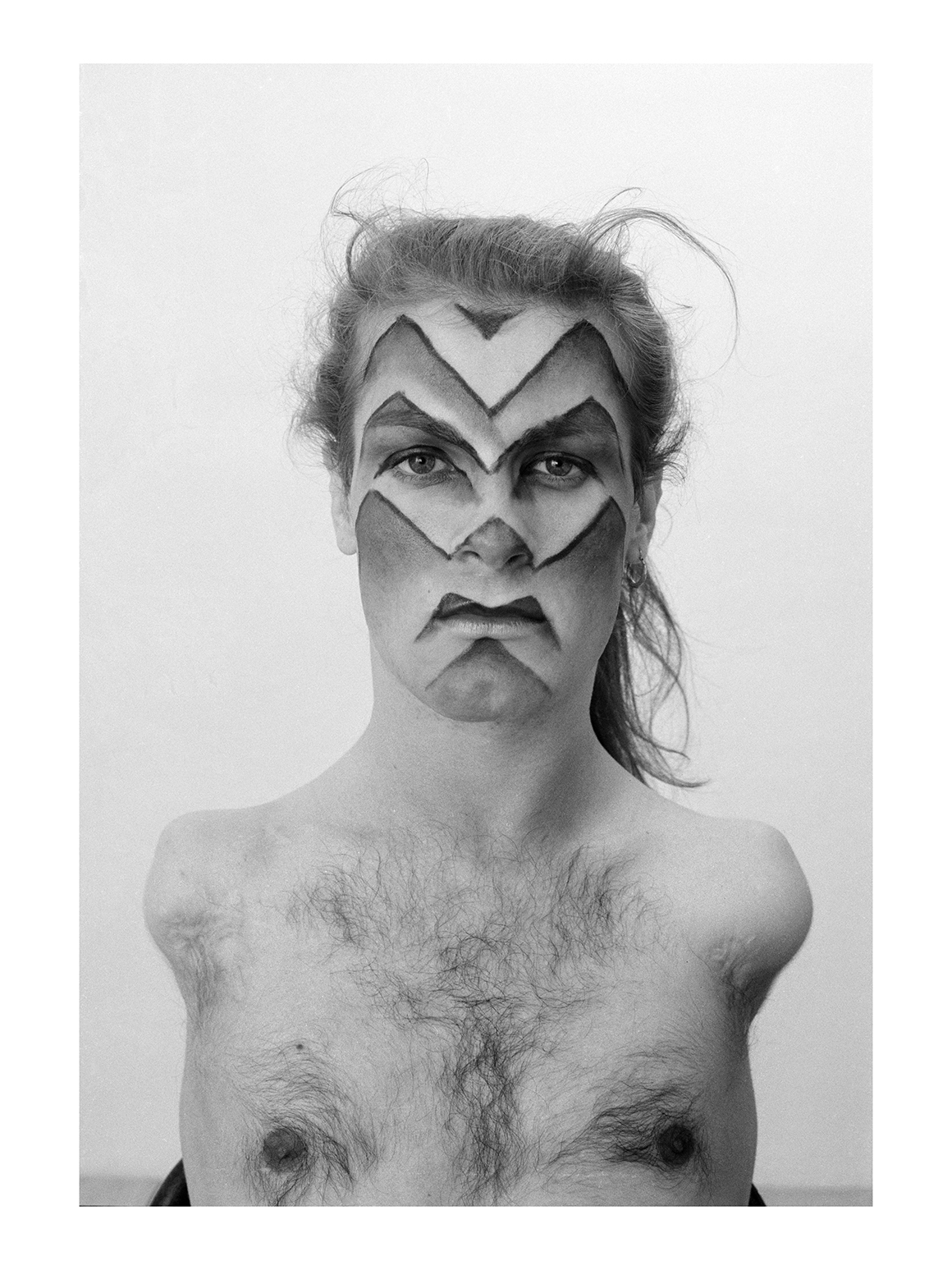

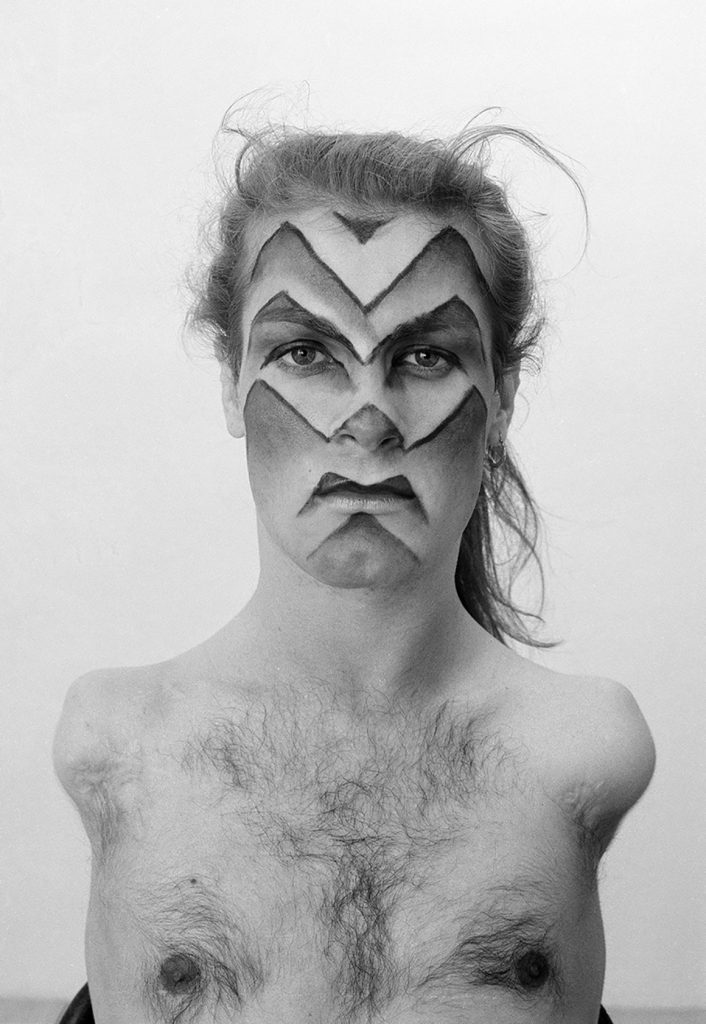

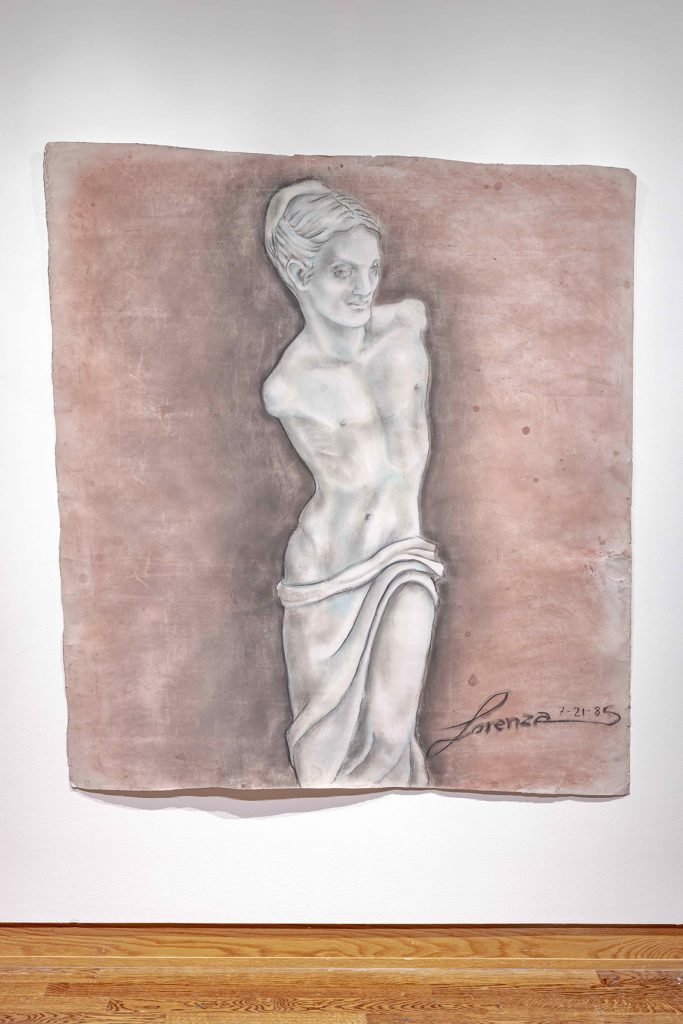

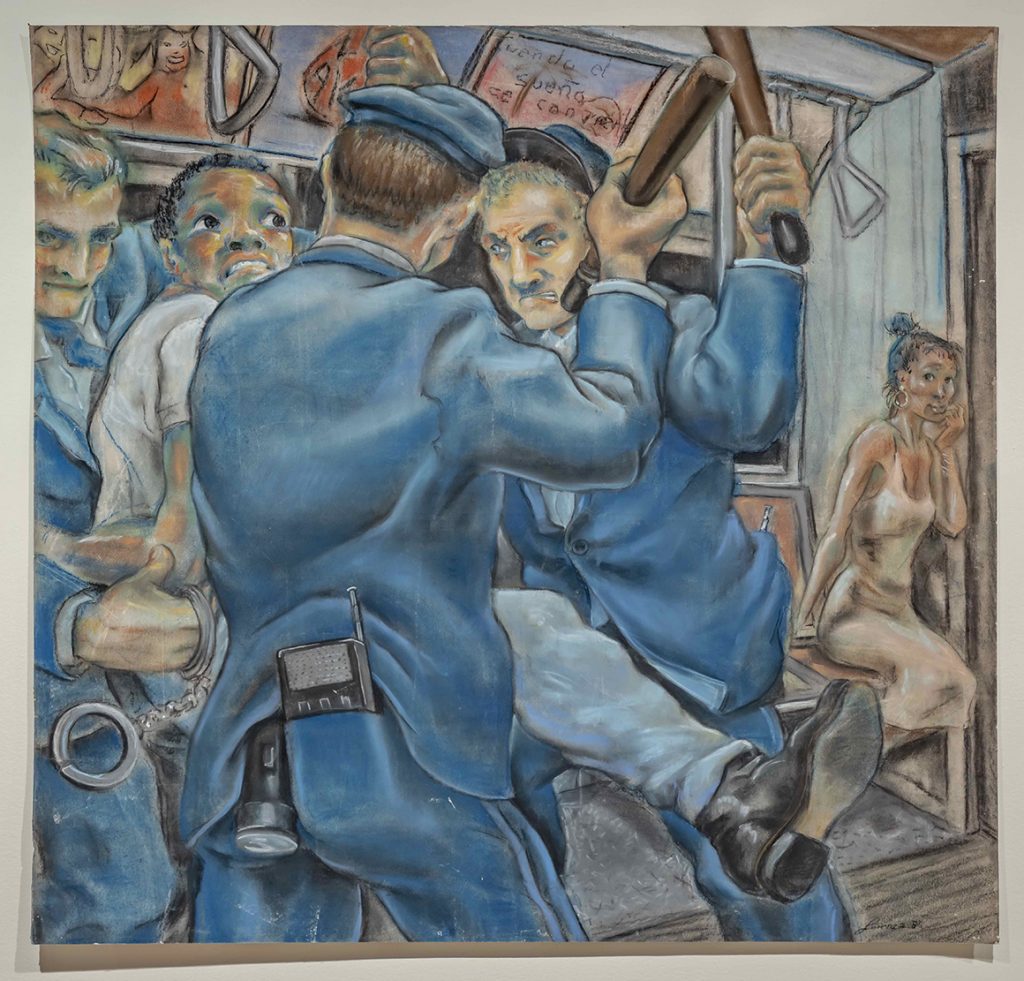

Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm, curated by philosopher Paul B. Preciado is the first major monographic survey of Chilean/German artist Lorenza Böttner’s lifework. A trans person without arms, Böttner worked in painting, dance, performance, photography and installation to generate a body of work that celebrated her standpoint and gender expression, resolutely transgressing and refusing any and all ableist and gender-normative prescriptions. Over sixteen years she produced more than two hundred works working with her mouth and feet and performing in the public arena of the street. The exhibition presents her work along with documentary videos as well as correspondence and photographs from her archive.

Biographies

Lorenza Böttner was born in 1959 in Chile and assigned male at birth. At the age of eight, s/he lost both arms following an accident while climbing an electricity pylon. In 1969, Irene Böttner and her childmoved to Germany for specialized treatment. While institutionalized s/he refused prosthetics and typical regimes of rehabilitation, and turned to dancing, drawing and painting. When studying at the Gesamthochschule Kassel from 1978 to 1984, s/he changed her/his name to Lorenza and began identifying and living publicly as a woman. During her short career, Lorenza traveled through Europe, the United States where a grant allowed her to study performance and dance at New York University, Steindhardt, and returned to visit Chile. In addition to working as an artist Lorenza modeled for Joel-Peter Witkin and Robert Mapplethorpe. She played Petra, the mascot for the 1992 Paralympic Games. And she was the subject of a documentary by Michael Stahlberg and the face of a Faber-Castell paint brand commercial. She died at the age of thirty-four in 1994 following AIDS-related complications.

ClosePaul B. Preciado is a writer, philosopher, curator and one of the leading thinkers in the study of gender and sexual politics. A Fulbright scholar he studied at the New School for Social Research in New York under Agnes Heller and Jacques Derrida. Later he obtained his doctorate in philosophy and the theory of architecture at Princeton University. Among his different assignments, he has been Curator of Public Programs of documenta 14 (Kassel/Athens), Head of Research of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (MACBA) and has taught Philosophy of the Body and Transfeminist Theory at Université Paris VIII-Saint Denis and at New York University. Following in the footsteps of Michel Foucault, Monique Wittig, Judith Butler and Donna Haraway he is the author of Countersexual Manifesto (trans. 2018); Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in The Pharmacopornographic Era (trans. 2013); Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (2019); An Apartment in Uranus: Chronicles of the Crossing (trans. 2020), which are key references for queer, trans and non-binary contemporary art and activism. His last book, Can the monster speak? will be published in English in 2021 by Semiotexte and Fitzcarraldo. He contributes on a regular basis to the print and online journals Libération and Médiapart. He was born in Spain and lives in Paris.

CloseESSAY

Paul B. Preciado

Overlooked by the dominant historiography of art until relatively recently, the work of Lorenza Böttner—an artistwho painted with her mouth and feet, and who used photography, drawing, dance, installation, and performanceas means of aesthetic expression, emerges today as an indispensable contribution to the criticism of bodily and gender normalization in the late twentieth century.

As exercises in resistance to the medical gaze that reduces the functionally diverse and trans body to the status of an exotic specimen and object, Lorenza Böttner’s works are characterized not only by the use ofself-fiction, the dissident imitation of visual styles from the history of art, and bodily experimentation, but also by criticism of the disciplinary divide between genders and genres, between painting, dance, performance, and photography, between object and subject, masculine and feminine, homosexuality and heterosexuality, the normative body and the trans body, between active and passive, and between valid and invalid. This exhibition,the first international retrospective dedicated to her, asks: In what frame of representation can a body makeitself visible as human? Who has the right to represent? Who is the represented? Can an image grant or deny abody political agency? How can a body construct an image to become a political subject? Is there any aesthetic difference between an image made with the hand and another made with the foot, or does this difference lie ina power relationship?

[…]

The complete essay can be viewed on the exhibition’s page and downloaded in the Texts and Documents section. A printed version is also available at the Gallery.

CloseEXPLORE

In her practice and life Lorenza Böttner was guided by an uncompromising commitment to her identity and position in contrast to normative categories of gender and ability. A range of documents identifying Lorenza can be found in the wall-mounted vitrine neighbouring the photo series Face Art and the documentary Lorenza: Portrait of an Artist. Consider the documents in the vitrine and ask:

Which documents are authored by Lorenza or addressed to her? Which documents come from organizations, institutions, or the state? Compare the different ways Lorenza is presented in this material. Extend your comparison to her experiments in self-portraiture, her personal accounts in the documentary, and research into freak shows.

CloseThrough her practice Lorenza commands attention to her self through portraiture and solo performance. Shift your focus to instances in the exhibition where there are multiple figures and where touch plays a role.

How are sex, eroticism and intimacy represented? Where does vulnerability arise? Where do the boundaries between bodies become blurred? When is Lorenza noticeably present and when is she absent? Where is solitude found? Alternatively, where and how do objects stand in for the body or bodies? And in what ways might Lorenza bring to question the hand’s status as the presumed privileged instrument of touch?

CloseA skilled seamstress, Lorenza sewed and designed many of her clothes and costumes for her performances, photo-shoots, and day-to-day life. These outfits celebrated her body and self, drew from fashion history and subcultures, and opened on to role-play and fantasy. In other instances, she donned costumes that risked narrowing a view on disability and gender, as Preciado observers about her role as Petra the mascot of the 1992 Paralympic Games.

As you move through the exhibition survey the role and place of clothing and costumes in Lorenza’s work. How does Lorenza design for herself—not only for her body as a person with limb differences, but for movement and for her desires? How does Lorenza work with classic or familiar designs? What possibilities does she outline in her more fantastic designs? When does she use costume to expose the body? When is costume used to hide or distort the body? And what of her designs for non-disabled bodies?

CloseUnderstanding that staring is a means of objectifying and exploiting people with disabilities and transgender people, study the different ways that Lorenza works with the audience’s gaze in order to subvert it.

Commencing with Lorenza’s Venus de Milo performance can you locate other works where she directs the audience’s gaze? In what ways does Lorenza use duration to draw the audience away from its comfortable distance? Where does Lorenza turn the audience’s gaze into an object of study? Where does Lorenza share her view of being the person stared at? What other forms of witnessing are at play in her work?

CloseKEYWORDS

Elaborated by Preciado in his book Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era (Feminist Press, 2013), pharmacopornographic accounts for capitalism’s control and production of sexual subjectivity. It is an extension of the term somatopolitical, as developed by philosopher Michel Foucault, somato- from the greek word for body. Where Foucault examined a long history through modernity of the surveillance and management of bodies, difference and desire, Preciado proposes that contemporary capitalism has since harnessed medical, neurological, and digital technology in order to further insert and fix itself within peoples’ bodies and psyches. The pharmacopornographic exploits mental, sexual, emotional and biological lives for profit, constructing consumers and workers tailored to its technologies, substances and procedures.

CloseEnfreakment refers to the cultural construction of the freak figure. By making a spectacle of disability, gender, sexuality and race, enfreakment puts difference on display, objectifying and casting people with non-normative bodies as others against the audience’s assumed normativity.

Disenfreakment, in turn, describes acts of taking hold of and retooling, recoding, and rethinking the categories of the freak. Disenfreakment turns enfreakment back on itself and puts its disempowering and denigrating aims on display. Where enfreakment identifies a person as a freak in order to control them, disenfreakment hijacks the codes of enfreakment and activates identity as an ever-changing process. The freak becomes a position of self-representation and a forum for speaking back to the audience, rather than submitting to them.

CloseOn Lorenza’s ever-changing role-play, Preciado writes: “Lorenza wasn’t simply transgender, she was transchronological.” Here Preciado casts Lorenza’s play with identity as a form of time travel. On its own “chronological” suggests an ordered passage of events over time. Qualified as “trans,” this linear progression is disrupted. To be transchronological is to interrupt and exceed time, to weave back and forth, to reveal history as a conglomerate of minor histories rather than one official narrative. In contrast to transhistorical, which describes something eternal, absolute and unchanged through the passage of time, transchronological can be thought of as an endless variation to and overlapping of time’s passage.

CloseAn abbreviation of pejorative cripple, crip reworks and reclaims the word as both a critical position and action. Contrary to its source word, it defines resistance to any norm based on one form of ability. It signals a refusal of disability rights that stop at recognition and integration while leaving the systems that lead to exclusion, oppression and exploitation unexamined and unchanged. As a verb, to crip is to centre disability and expose the contradictions and violence of a culture and society that privileges ability. Crip can be read as a radical process open to intersections with other positions and experiences. See Preciado’s use of trans-crip in his curator’s essay and queer crip pride and trans-crip love in the wall texts.

CloseDOCUMENTARY

Lorenza: Portrait of an Artist. Directed by Michael Stahlberg, 1991.

CloseAUDIO DESCRIPTIONS

Offered for people who are blind or with low vision these descriptions introduce the exhibition premise and focus on five works representing different facets of Lorenza’s practice. They are also available for anyone who cannot visit the exhibition in person and is interested in engaging with art through spoken description.

CloseBIBLIOGRAPHY

Can the Monster Speak? Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts. Translated from the French by Frank Wynne. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2021.

An Apartment on Uranus: Chronicles of the Crossing. Translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2020.

Counter-Sexual Manifesto. Translated from the French by Kevin Gerry Dunn. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics. New York: Zone Books, 2014.

Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic era. Translated from the French byBruce Benderson. New York: The Feminist Press, 2013.

CloseBaril, Alexandre. “Transness as Debility: Rethinking Intersections Between Trans and Disabled Embodiments.” Feminist Review 111 (215): 59-74.

Califa, Pat. Sex Changes: The Politics of Transgenderism. New Jersey: Cleis Press, 1997.

Charlton, James I. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Oakland: University of California Press, 2000.

Crutchfield, Susan and Marcy Epstein, dir. Points of Contact: Disability, Art, and Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Clare, Eli. Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness and Liberation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015.

Kaffer, Allison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Kuppers, Petra. Studying Disability Arts and Culture: An Introduction. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.

McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Namaste, Vivian. Invisible lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Close