IGNITION is an annual exhibition that features new work by students currently enrolled in the Studio Arts or Humanities graduate programs at Concordia University. It provides an up and coming generation of artists with a unique opportunity to present ambitious, interdisciplinary works in the professional context of a gallery with a national and international profile. It places an emphasis on critical, innovative, and experimental work, engaging in the exploration and consideration of diverse media and practices. IGNITION is of interest to all students and faculty, the art community, and the general public.

April 23 – May 21, 2022

Pedro Barbáchano, Snack Witch aka Joni Cheung, Jin Heewoong, Kevin Jung-Hoo Park, Christy Kunitzky, Laurel Rennie, Aman Sandhu and Holly Timpener

Projects selected by Marie Martraire and Michèle Thériault

The eight artists in IGNITION 17 share their personal lived experiences, political reflections, and poetic engagements with realities that have affected us and our communities for centuries: experiences of migration, (mis/non)representation of our identities and histories, power relations, and unconscious biases. Their installation, photographs, texts, moving images, or textile works not only decry long-standing problems catalyzed by the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, they also propose strategies such as collective actions, radical care, and self-work to effect structural, institutional, and personal change.

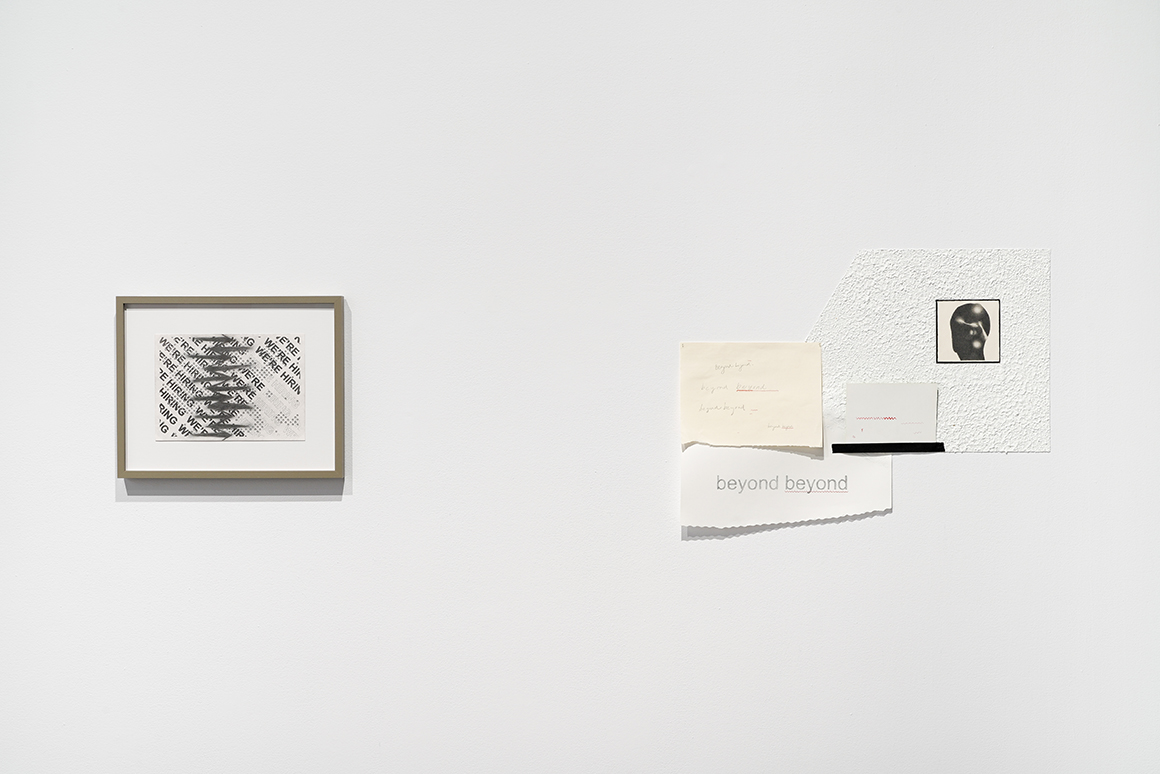

Read moreIn the gallery’s main window facing the atrium, Aman Sandhu’s text-based work and three drawings installed on the inside wall speak to structural racism in cultural and educational institutions through the recent popularity of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. Since the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, universities, museums, and other institutions have increasingly offered job openings, exhibitions, and grants for racialized candidates to diversify their workplaces and programs. Yet, organizations do not necessarily tackle how they contribute to upholding white supremacist cultures. Like the window texts “WE’RE HIRING” and “WERE HIRING” suggest, complacency rather than real change will soon conclude these efforts.

In the first room, Holly Timpener and Pedro Barbáchano engage with queer experiences of time and space as well as strategies of care. Holly Timpener’s collaborative performance explores the transformative power of the collective embodiment of queer time—the articulation of time experienced by queer people. Four queer performers living in different parts of the world remotely convened to give, at the same moment, a tangible or visible form to queer time for each other and their immediate physical surroundings. As the post-performance writings describe, this communal yet individual practice led to increased connection, inspiration, and a sense of support. Directly across from Timpener’s installation, Pedro Barbáchano’s photographs make up an archive of queer self-portraits, often absent in museum collections. The larger body of work that the pictures are part of begins with nude profile pictures collected from various anonymous dating apps, like Grindr, in places where queerness is considered illegal and prosecuted. The artist then eliminates any of their temporal markers or distinctive signs that could identify the subjects and transforms the nudes into 3D sculptures in a style evocative of sculptures from antiquity. He rephotographs these objects against a neutral background, then finally displays the documentary-like still lifes in exhibitions while inserting others back into the imagery repository of local national museums. Destabilizing the status of the historical document and questioning the institution’s role in preserving queer histories, the works act as a source for knowledge production and visibility of queer individual bodies and collective experiences. Continuing a reflection on how to rewrite history, Kevin Jung-Hoo Park’sthree projected videos address the role of films in colonial efforts. Films have contributed to maintaining support for colonization in the metropoles by exploiting the modern fascination for (moving) images, which are believed to “deliver what they portray”[1]. They indeed facilitated the manufacture and dissemination of idealized representations of the colonies that often emphasized the modernizing aspects of colonization and spoke to the worldviews of their audiences. Each projection is an edited version of a film shot by the Lumière brothers in French Indochina (now Vietnam) in the late nineteenth century, in which each frame is extended to twenty-four seconds. In Truth-Production 24 Seconds A Time (And Every Cut is a Fun Fact): Lumière Actualités (Indochina) #1, the movements of children rushing to pick up the coins thrown by two white women are decomposed, slowed down, and dissected. This intervention makes the colonial gaze visible by giving viewers time to analyze the binary, constructed separation between the filmmaker/colonizer and the observed positioned as the “Other.” By staging this conversation on mediated reality and the role of moving image, Park’s works speak to issues of memory and written history through the lenses of geopolitics, colonialism, and migration.

Moving into the contiguous back rooms, Snack Witch aka Joni Cheung and Jin Heewoong speak to experiences of migration, displacement, and home. Across from the reception desk, Snack Witch aka Joni Cheung presents multiple episodes from her YouTube cooking show Soba’s Corner: A Chinese-Canadian Cooking Show, underway since 2020. At first glance, each program appears as a typical tutorial on preparing Chinese-Canadian dishes from different provinces, such as the Alberta Ginger Beef Rumble or the Montreal Peanut Butter Dumpling. The chef greets her subscribers, lays out all the ingredients on the kitchen counter, and starts performing different actions while explaining the recipe step-by-step. Yet, the closed captions do not directly transcribe the chef’s descriptions. Instead, they comment on migration experiences across cultures through the lens of food—perceptions of authenticity and identity, creation of home, feelings of in-betweenness, cooking as a ritual, and more. In the room right behind Cheung’s work, Jin Heewoong’s installations visually translate the sense of strangeness and the violence that arise from the experiences of migrating to a country other than one’s own and acclimatizing to an unfamiliar culture. The works are initiated by collecting used objects that were either discarded, abandoned, or that he previously owned. The artist then repurposes them into various installations that create incongruous, sometimes risky situations that tease out unusual connections between the different elements. An antenna entangled with a drying rack appears as decoration for a cardboard table, while a ladder may collapse at any moment due to its precarious balance. The experience of time and the various power dynamics in Jin’s works embody the daily events an individual faces when negotiating migration as an Asian migrant living in the West.

In the fourth and last room, Christy Kunitzky’s ambiguous installation Pets, consisting of three figures tightly wrapped in textile and standing in mulch, speaks to issues of capitalism and care. On the one hand, the thick fabrics seem to protect the structures just as we cover outdoor trees during the winter to protect them from death. On the other hand, the tightly wrapped cords could also be suffocating the undiscernible silhouettes while restraining their movements. This tension translates the contradictory goals of health care systems under capitalism and the conditional access to essential care—they must care for patients while maximizing profits. While doubts toward institutional care systems arise, Laurel Rennie’s quilt works ground us back in the potential of our individual memories. The artist sees quilting and stitching as meditation processes to explore imperceptible moments and the often unconscious labor that we perform in our daily lives. The artist adopts an intuitive and free-flowing making process to draw and assemble texts, imagery, and textures. Like the symbols of the trees visible in one of her wall pieces, her works ponder cycles of evolution and transformation, order and distortion, and healing and care.

Marie Martraire

[1] Tom Gunning, “The Whole World Within Reach,” in Virtual Voyages, ed. Jeffrey Ruoff (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006) 25-41, 30.

Close