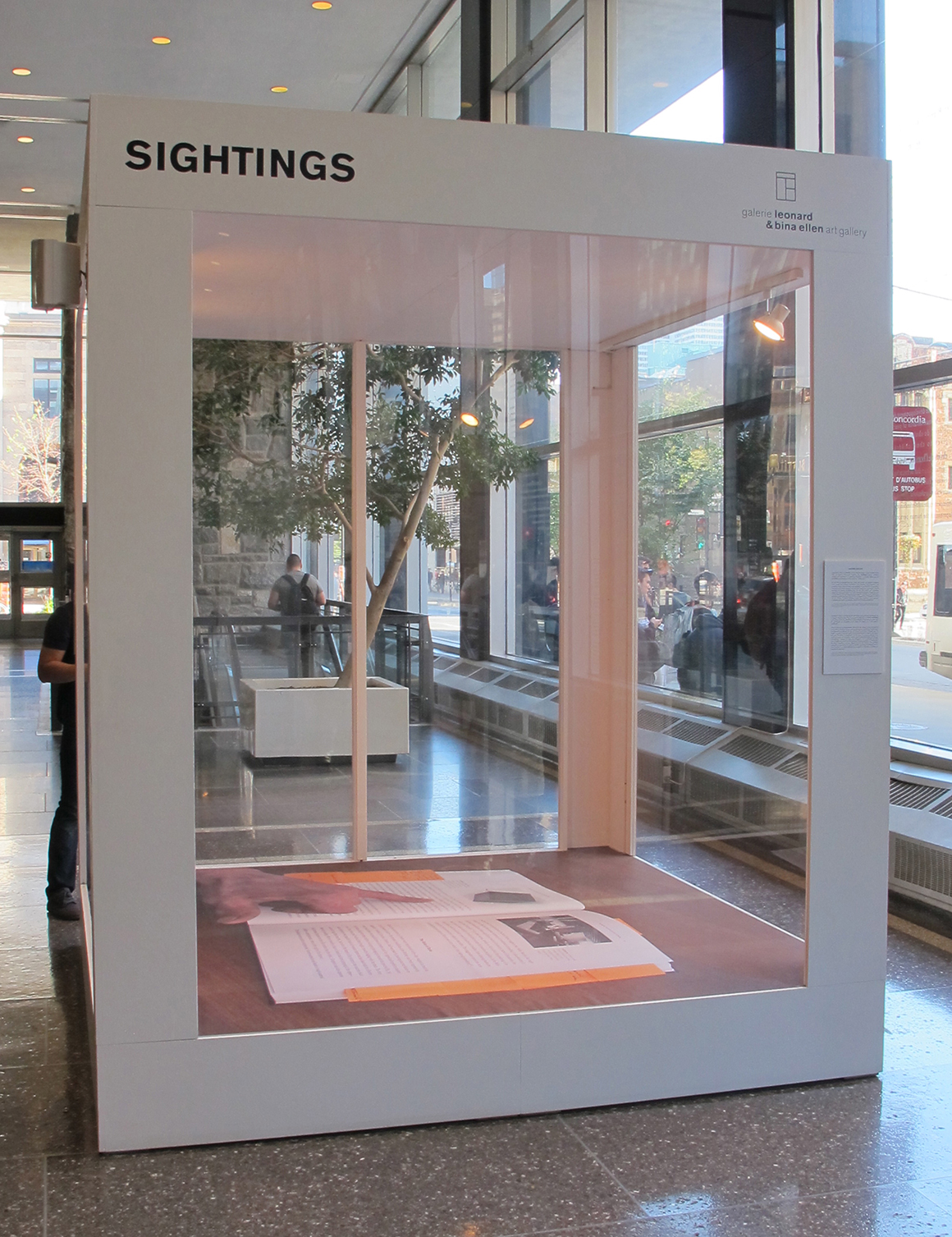

Launched in 2012 in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery’s Permanent Collection, the SIGHTINGS satellite exhibition program was conceived as an experimental platform to critically reflect upon the possibilities and limitations of the modernist “white cube”. For the 2015-16 programming year, artists and curators are invited to examine more closely the invisible mechanisms that condition the production and circulation of art, and to propose new strategies to present them to the public. Focused on the notion of labour and the issues raised by an “immaterial” cultural economy, the projects developed over the next few months will investigate aspects of the art system that are usually overlooked by viewers. Among these are the distribution of roles among art world protagonists (curators, artists, technicians, assistants, programmers etc.); the tensions that govern their respective activities; and the division of labour (between manual and intellectual work, between conception and making, and between creative and discursive production).

SIGHTINGS is located on the ground floor of the Hall Building at 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West

September 23, 2015 – January 10, 2016

A project by Karine Savard

The soundtrack accompanying the project is available here.

A transcript of the dialogue is available for download here.

These documents, as well as a copy of the book Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era by Julia Bryan-Wilson can also be consulted onsite at the gallery.

Promenades

Promenades is the link between the Ellen Gallery in the McConnell Library Building and the SIGHTINGS exhibition cube in the Hall Building of Concordia’s downtown university campus. The walk from one site to the other lasts five minutes at the most.

Robert Walser’s famous essay The Walk unfolds as an iridescent prism of observations and connective thoughts on the occasion of a short walk through a city. We are asking artists, writers, and other contributors involved in SIGHTINGS, to develop for Promenades a seemingly ephemeral thought as it occurred to them during the making of the work on display.

These thoughts may be expressed in the form of a narrative tour, a performance, a short lecture, a reading. The only formal constraints are that the gathering begins at one of the two sites, and ends at the other, and that the Promenade last no longer than thirty minutes.

Promenades is a reoccurring format. If you haven’t already, subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed.

First Promenade

Karine Savard

Wednesday, November 11, 2015, 12 PM

More information on the Promenade here.

In 1961, the American artist Robert Morris created a box into which he inserted a recording of the sounds generated by its making. Presented with a soundtrack of its construction, the work Box with the Sound of Its Own Making reveals the production process directly through the produced object, thus challenging the separation that the capitalist system tends to maintain between individuals, their actions and the products of their labour.1

In her book Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson contextualizes this work in relation to the exhibition Robert Morris: Recent Works that was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970.2 For this exhibition, Morris created monumental installations with the help of a large team of workers, using chance and automated processes in order to put into perspective the traditional privilege granted to the skill and authority of the artist. While the assistants were setting up, the exhibition was open to the public, thus making the collaborative nature of the artistic work apparent. Echoing the era’s socio-political climate — characterised by frequent protests against the Vietnam war and many uprisings initiated by teacher, student and worker unions — Morris subsequently decided to strike against the art system and shut down the exhibition several weeks before its scheduled close.

According to Bryan-Wilson, Morris’s efforts to transpose industrial materials into art objects and to stage physical labour testify, in a contradictory way, to a nostalgia for a preindustrial era as well as to a loss of masculinity associated with tough manual work. The author also underlines ambiguities regarding the parallel made between the artist and the construction workers. For example, a series of photographs that document the installation process shows Morris both in the role of a worker, who operates a forklift or lifts a large wood beam, and in the role of a foreman proudly puffing on a cigar.

Taking the Box with the Sound of Its Own Making and Julia Bryan-Wilson’s critique as starting points, I explored what the relationship between worker and artist may involve today. Together with my father who is a carpenter-joiner, I staged a repetition of Morris’ work with the aim of producing a video of the construction of a box. In this case, the term “repetition” is used to mean both the reenactment of a work of art and, also the work of the rehearsal when performers fine tune their interpretation. Through this approach, I sought to reveal the staging and filming process inherent to artistic work.

Read moreOn a 60 minutes long soundtrack, which has been edited in order to emphasize some sections with long gaps of silence, one can hear the conversation between my father and I as we are practicing for the prospective production of a video documenting the process of making a box. Together, we look at the documentation related to the work Box with the Sound of Its Own Making and discuss issues raised by this work. We select various tools and material required to build the box and exchange about the aesthetical aspect and function of the various instruments, the “beauty” associated with some of the gestures and the antique character of mechanical tools in comparison with the efficiency of today’s electric tools. While my father describes the actions and gestures, as well as the tools and materials required for the construction of the box (saw bench, hammer, square edge, nails), mimicking the sounds they will make, I mention the possibilities and limitations of image production technologies (film camera, recording device, magic arm). The filial relationship underpinning this dialogue instills it with a certain intimacy that belies the commonplace cliché of the virile and macho construction worker, and prompts one to rethink the relation between manual skills, linked to tools, and intellectual knowledge as represented by books. The parallel between the carpenter’s activity and the artist’s makes it possible to address several current issues in art, notably: the divide between manual and intellectual work, the importance of know-how, or technè; the concept of the division of labour and its recognition within the capitalist system; and the intervention of aesthetic judgements.

This installation combines a soundtrack publicly disseminated via speakers and a photographic print of the book Art Workers placed on the interior bottom surface of the exhibition cube. Thus, the visitor can experience the work’s visual and sound components in a distracted or partial manner, or can study them in a more in-depth way that will reveal the different levels of information at play in the image, as well as the various relationships existing between work and art that arose during the conversation. Moreover, the contrast between a rapid consumption of the image and a proposal that calls for a thoughtful involvement is an important feature of the approach guiding this project.

- Helen Molesworth, Work Ethic (Baltimore: The Baltimore Museum of Art; University Park, Penn State University Press, 2003), 113.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley : University of California Press, 2009), 90.

Karine Savard is an artist who designs film posters (Incendies, La vie d’Adèle, C.R.A.Z.Y.). She is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Études et pratiques des arts at Université du Québec à Montréal. Her research addresses the representations of labour and the collaborations between art and industry (À bientôt J’espère by Chris Marker, Labour in a Single Shot by Harun Farocki, Artist Placement Group). In her artistic practice, Karine Savard appropriates the presentation mechanisms of publicity in order to produce stealth interventions that integrate directly into the urban fabric. Recently, she explored a possible relationship between the skills and tools of a construction worker and the instruments used for the manipulation of images, in light of the transformation from an industrially-based economy to one that is information- and service-based economy. which is henceforth based on information and production of services. Karine Savard received a scholarship from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture.

Acknowledgements: Katrie Chagnon, Hugues Duguas, Pierre Julien, Stéphane Lebigot, Pavel Pavlov, André Savard, Michèle Thériault, David Tomas, Adam Wanderer, Giulio Wehrli and PRIM.